The Threeness of the World (2/6)

On the Reality of Maps and Territories

For a personal and political note to readers in the US, please see the first footnote.1

My friend and fellow traveller Alex Gomez Martin of The Pari Centre is doing a four-week course on PSI research and related phenomena at The Centre for Myth, Cosmology and the Sacred, starting on Wednesday. It’s likely to be very good.

I am a co-founder and one of the main organisers of The Realisation Festival from June 26-29. We have sold over half our tickets, and that’s before a few exciting speaker announcements to follow this week, so hurry, as the saying goes, while stocks last.

Thanks for being here, and special thanks to recent subscribers and paid subscribers including Rick, Ann, Milla, Susan, Suzanne, Richard, Pieter and others who help keep the show on the road. 🙏🙏🙏2

You might want to read The Threeness of the World (1) before continuing, but it’s not essential.

Please forgive the length of what follows. I am still finding my way. Next time we’ll get into some actual models of threeness.

Much of what follows is what my literary agent would unflatteringly call ‘throat-clearing’. If you want to sell a book, you should not spend too much time with lateral observations, setting the scene or making caveats - like I’m doing now. Instead, you should grab the reader’s attention, hold them tight, and only let them go at the end, begging for more.

But I am not trying to sell a book here. Sometimes there is no point as such. Sometimes it takes a while to get to the point, and points are not the sine qua non of worthwhile writing. Sometimes circles are what you need, circling, and if you need to embellish that idea with an adjective it’s the hermeneutic circle, enriching meaning through “iterative recontextualisation” by going round and round over the same or similar terrain until what you get is not ‘the point’, but understanding, or even, wait for it, that carnival of self-congratulation called…transformation.

After introducing the inquiry space of the metaphysics of threeness in the prior post, I want to establish what it means to say that we live in three kinds of reality. What kind of claim is that? And what’s the point of it? 🙃

**

Timothy Morton once said that the problem with global warming is that it doesn’t go golfing at the weekend. I won’t get diverted by hyperobjects, but that’s another way to say that you can’t easily locate global warming in time and space. I believe our minds can furtively creep up on phenomena of that multiplicity and scale though, which is better than epistemic capitulation and the nihilism that can result.

On climate, there is ‘the science’ which contends with greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and their impact on land, ice and sea; and food and water. There is ‘the experience’ of climate change not only in terms of homes being burnt down or flooded but also in terms of widespread denial, anxiety, anger and/or guilt. And there is something like ‘the politics’, which is about how the discussion impacts the economy and unfolds culturally, the relative salience of the issue, the justice of loss and damage, thousands of civil society organisations, the scope for international cooperation, the UN climate regime etc. All of the above is ‘climate change’, and these three worlds need to be in conversation, but they are different worlds, calling for distinct kinds of discernment and agency. Doubtless, it is possible to find aspects of phenomena that don’t quite fit, or overlap, but the model only has to be useful, not perfect. (If you’re curious about my evolving relationship with the climate crisis and why I shifted focus to the metacrisis please see Dancing with a Permanent Emergency.)

**

When I gave my workshop on The Flip, The Formation and the Fun in Montreal I set the scene with my definition of the metacrisis, which includes a reference to ‘reality’. And while that was not quite like a red rag to a bull, my first question of the evening, about three minutes in, was: “Are you ready to define reality?”.

As you can see, I was a little thrown, said “No”, and eased my way back into the main conversation. I might have mentioned the top-notch philosophical joke by Robin Williams: “Reality? What a concept!”, but I forgot. And the line I slightly misrepresented was by the Sci-fi writer Philip K. Dick: “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn't go away.”

I share this moment now because it was a missed opportunity to speak of the threeness of the world. Indeed, foundational threeness is part of the argument for why the current state of the world is best characterised as a metacrisis and not a polycrisis. It is precisely because the world is compromised of fundamentally different qualities of things that are real, but not necessarily empirical or actual (see Bhaskar below) that we have to get within the crisis, and between the crises, while transcending crisis thinking altogether (see Prefixing the World).

**

When I say we live in three worlds I mean something like this:

There is a world ‘out there’ - an objective exterior world of processes and events that can operate entirely independently of human perception and is mostly the concern of natural science.

There is a world ‘in here’ - a subjective interior world of consciousness, thoughts and feelings, full of meaning and mattering; the concern of philosophy, religions, and psychology.

There is (in most contexts) a shared world ‘between us’ and/or ‘for us’, an inter-subjective and inter-objective life of culture and ideas and institutions that forms a socially constructed reality and patterns of collective psychology; that world is of interest to social scientists and is the domain of politics broadly conceived.

These three worlds interact and are all part of the same world that is both one and many, but they are different kinds of things, known and valued and changeable in different ways; being aware of this underlying structure helps us to understand what we are doing here, what we can do, and what we should do. As indicated in the previous post, many theorists have some version of this three-fold structure, and we’ll return to them (I’m excited to get to Peirce and Bourgeault especially, but we’ll have to go via a few others including Plato, Popper, Habermas, Archer and Harris). The words used to describe these distinctions vary, they don’t all mean the same thing, there are overlaps and fuzzy edges, but there’s still a clear pattern to be disclosed. My preference, conjured in collaboration with Tomas Bjorkman when we established Perspectiva almost a decade ago, is to speak of systems, souls, and society.

This three-world perspective is foundational in a morphological rather than substantive sense. I like the word morphology. This quasi-architectural term means the study of form or forms - an inquiry into the shape, structure, and function of things. Threeness provides the meta-theoretical scaffolding to build particular theories and practices for specific purposes, i.e. it is not a theory as such, but it facilitates conversations between theories and therefore illuminates and informs practice.3

This three-world perspective need not always take sides in perennial philosophical debates about the nature of matter, consciousness or society. However, it does say that if you want to be intelligible about the world in a way that is expansive and inclusive enough to be helpful without being overwhelming, these three constitutive worlds are a good place to start, maybe the only place to start well, and probably the best place to start. What this distinction between worlds serves to highlight - and is essential for - is the varied ontology, epistemology, and axiology of different kinds of phenomena; how something is, how something is known and how something is valued is very different depending on which of the three worlds you are talking about.4

To illustrate, coming back to the metacrisis context, the three-world perspective helps us to distinguish between the world characterised by ecological collapse, exponential technology, economic and bio-precarity (‘systems’) with another kind of world that's characterised by misperception, confusion, anxiety, despair and hope (‘souls’) and another that's characterised by fragile democracies, misinformation, wars, and educational failure (‘society’). There is ultimately one world, and it's all happening simultaneously, but that one world contains three distinct elements of reality and three distinct ways of knowing and valuing it, and they all require different kinds of attention and action. The objective world may call for facts and empirical measurement, but the subjective world calls for meaning, mythos and hermeneutics; while the shared world calls for dialogue, ritual, art, collective agency and so on.5

If civil society wants to understand how everything fits together, what it means, and what we should try to do about it, we will benefit from talking in a way that elucidates the relationship between the three worlds; they are all real, and they all matter. We need an educational renaissance (‘the formation’) to create a generation that can move between these forms of existence and ways of knowing with discerning agility. That’s a critical part of the ‘H2plus method’.

If we leave God aside for a moment (sorry God) I could say this: I believe the world is an evolving relationship between systems, souls, and society. Our world changes depending on how that relationship changes and we have collective responsibility for the quality of that relationship.

It’s a relief to get that out, but the reader might wonder about the status of this claim. Are the three worlds just a map, the territory, or is something else going on?

***

At some point in life, perhaps while looking at a tree and remembering we live on a planet, or while struggling to find common ground with an adversary who can’t see your perspective; or perhaps while reading The Upanishads, Wittgenstein, Rosa, Pirsig, Bourgeault, or one of Bayo Akomolafe’s dizzying Linkedin posts. Or perhaps just as likely while meditating, doing the headstand, during a coital surprise, or maybe just completely out of the blue…At some point, we grasp that reality is much more than our mind can ever possibly fathom, that it will never ‘fit’ perfectly with the structures we seek to impose on it, and that to seek to capture its boundless mystery in any net of words is comical, if not tragic.

Those folks who said the map is not the territory were not kidding. Reality as it presents itself is different from reality as it is represented.

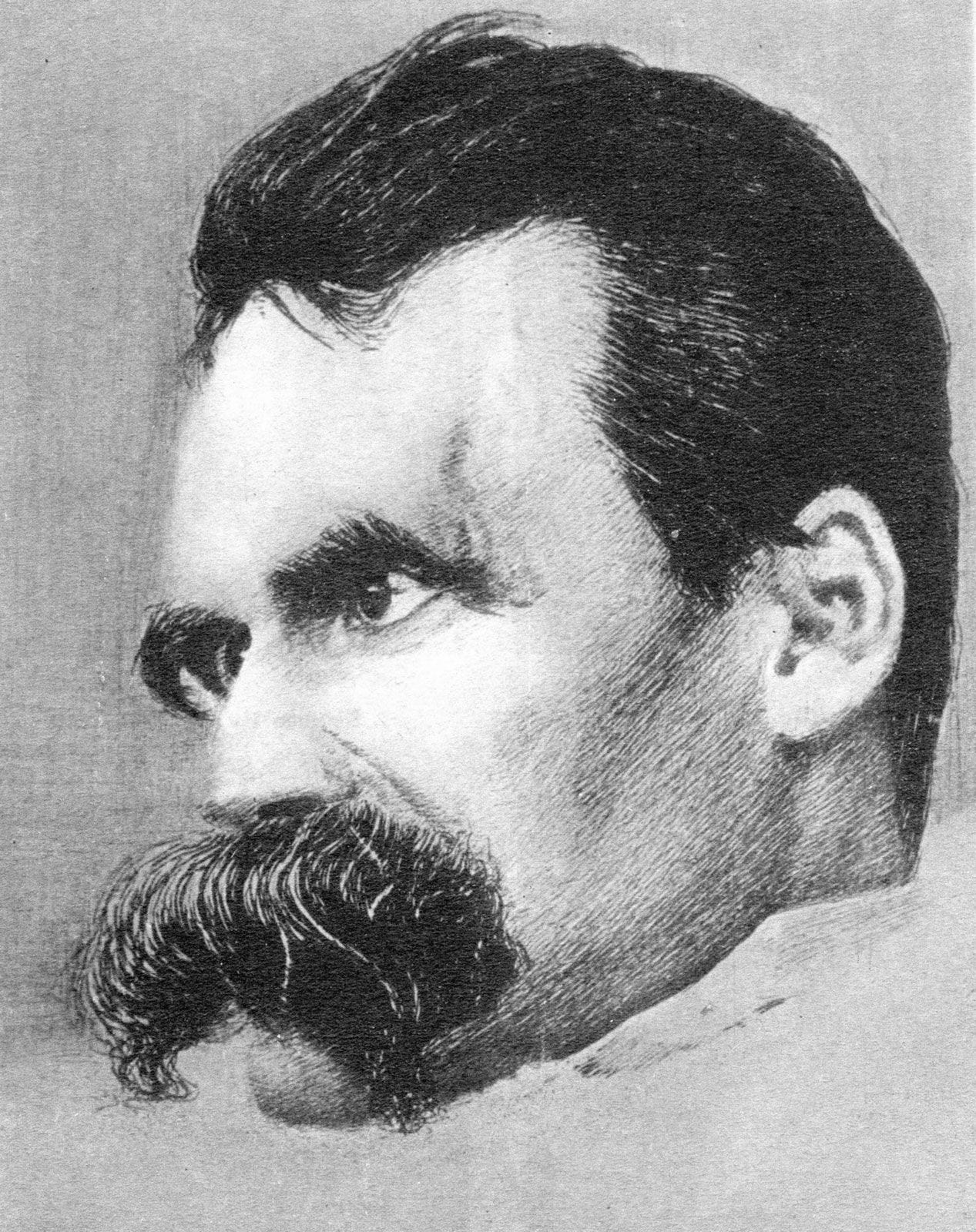

The history of philosophy reflects this point. There are versions of this ‘the map is not the territory’ in the lugubrious ambience of Plato’s Cave; in Aristotle’s distinction between substance and accidents which tells us, roughly, why a tree without leaves is still a tree. Jumping forward, the distinction is carried in Kant’s phenomenal/noumenal distinction which informed his theory of the sublime as an intimation of the limits of human perception - it’s all so vast and beyond us. The map/territory distinction begins to morph in Schopenhauer’s distinction between will and representation because beneath all appearances is not exactly territory but more like a raw endless striving. That striving manifests as representations in the world, for instance in Nietzsche’s moustache, which always looked pretty real to me; and yet Nietzsche casts doubt on the idea of something more real that lies beyond or behind appearances. A gratuitous way to put that point is to ask: is there anything more real than Nietzsche’s moustache?

I am only partly joking. In his 1873 essay: "On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense" Nietzsche questions whether there is anything like a true objective ‘territory’.

"What then is truth? A mobile army of metaphors, metonymies, anthropomorphisms, in short, a sum of human relations which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished, and which, after long use, seem firm, canonical, and obligatory to a people: truths are illusions which we have forgotten are illusions; they are metaphors that have become worn out and have been drained of sensuous force, coins which have lost their embossing and are now considered as metal and no longer as coins."

Impressive, but is it right? I don’t think so. And not just because I trust Sri Aurobindo’s beard more than Nietzsche’s moustache.

Aurobindo has his doubts about Nietzsche. In his 1915 essay The Type of Superman published in Arya, his description is memorably withering:

...The mystic of will-worship, the troubled, profound, half-luminous Hellenising Slav with his strange clarities, his violent half-ideas, his rare gleaming intuitions that came marked with the stamp of an absolute truth and sovereignty of light. But Nietzsche was an apostle who never entirely understood his own message...

Aurobindo’s contention is that Nietzsche was not connected to the only touchstone that could grant the validity of his ideas: nature’s moral evolution. It is fitting therefore that Aurobindo makes the ultimate superpower - the capacity of love to conquer even death - a defining theme of his epic poem, Savitri (my father-in-law Professor Ramakrishna translated it from English to Telugu and asked me to write the foreword).

However, what Nietzsche believed about truth and objectivity is echoed and refined by a wide variety of distinguished postmodern theorists who question whether there is anything really real beyond representation, signs and discourse. To take one of many examples, in his book Simulacra and Simulation (1981), Jean Baudrillard suggests that we live not in reality but in hyperreality - a world in which the signs and symbols that we use, conditioned by modern media, no longer refer to the real world but to an intersubjective world of other signs and symbols; a trap of self-replicating simulation - that’s the kind of world where every moment reminds you of a social media post, or makes you want to create one.

This kind of argument is further developed in the work of a-modern or non-modern theorists, particularly the brilliant Bruno Latour who questions the whole idea of modernity and postmodernity but continues to argue that map-making is a function of power (“We were never modern”, says Latour). For Latour, the difference between maps and territories is not about approximation versus reality but about the power relations that maps bring into being. Latour says that every representation is an intervention in the world, not just a reflection of it. So yes, the map is not the territory, and yes, the territory is so full of maps that it’s sometimes hard to tease them apart- both points have some validity. Latour’s point, however, is that maps actually shape the territory, for instance through the conceptual zombie of the political spectrum. He makes this case in Down to Earth, a short book to help reconceive politics today that I cannot recommend highly enough. (When I hear people using left and right unreflectively, I recognise the need for communicative pragmatism, but I also take it as a signal that they are not really thinking).6

**

At this point, I need to bring Roy Bhaskar into the room, particularly his notion of ‘the epistemic fallacy’ - the widespread tendency to conflate questions of what we know or can know with questions of what exists. This fallacy prevents us from recognizing deeper, causally active mechanisms that may not be directly observable. Qi and prana and chakras come to mind, though Bhaskar would probably not go there. Patriarchy, racism or ideology however are also real and causal in this way. The epistemic fallacy matters because there can be ontological structure and depth that is not perceptible or measurable (the empirical) and perhaps not even manifest (the actual) but still latent, present, operative, relevant and real. This empirical/actual/real distinction is useful (and threefold) because it implies that within the realm of The Real there can be ontological depth and structure. Indeed, in his later work on meta-reality Bhaskar was interested in how a pervading underlying oneness or ‘ground state’ informed an emancipatory politics. There is something generative and creative about unseen reality that is neither empirical nor actual but nonetheless powerful and malleable; it is up to us to shape it, and thereby make history.

The world is not only structured and differentiated, but it is also changing. And social structures, unlike natural ones, depend upon human activity for their reproduction or transformation.

Roy Bhaskar (The Possibility of Naturalism, 1979)

**

I am trying to establish in what sense the threeness of the world is real, and here’s a useful comparison:

When I was doing my PhD on the nature of wisdom about twenty years ago I remember a few months grappling with what kind of reality wisdom had - where exactly was it in the world, what did it mean for it to exist, or to know it? Was it some kind of pattern of neural activity, was it a form of perception or behaviour, was it a vague honorific notion unworthy of scientific inquiry, or was it in some sense necessarily ambiguous and meaningful in particular social contexts but not in others? At that time, I went down a few wonderful rabbit holes and met some nice rabbits advocating constructionism and constructivism. At some point, I stumbled on this quotation:

A key fits if it opens the lock. The fit describes the capacity of the key, not of the lock. Thanks to professional burglars we know only too well that there are many keys that are shaped quite differently from our own but which nevertheless unlock our doors….From the radical constructivist point of view, all of us- scientists, philosophers, laymen, school children, animals, and indeed, any kind of living organism-face an environment as the burglar faces a lock that he has to unlock in order to get at the loot. (Von Glaserfeld 1984: 21)

I disagree with the second sentence. The fit describes both the capacity of the lock and the capacity of the key; it’s just that while the lock has one relatively unyielding shape, the key can assume more than one shape to fit it. That’s why I am not a postmodernist or radical constructivist - I don’t think reality is entirely invented or fabricated. I do believe there is a world ‘out there’ ‘behind things’ that acts as a kind of creative constraint and field of potentiality. However, I don’t think that world is the only defining feature of reality, just a key part of it. You could say reality is the lock, the key and the burglar picking the lock to get at the loot.

And there’s another intimation of threeness - a subject and an object and something distinct from either - an activity, a context, a process of change. It’s a lot for an unsuspecting burglar.

***

Near the start of The Matter with Things, Iain McGilchrist juxtaposes naive realism (Reality Out There - ROT) with naive idealism (Made Up Miraculously by Ourselves - MUMBO). He also distinguishes between inventing reality and participating in it. The claim that we live in three worlds is neither ROT nor MUMBO, but more like a guide to informed participation. In a non-trivial sense, the three worlds are both map and territory. Consider the elegant line of Buddhist(ish) Cognitive Scientist Evan Thompson:

Although some illusions are constructions, not all constructions are illusions.

This line is quoted, with approval, by Cynthia Bourgeault at the beginning of The Eye of the Heart before she outlines her beautifully intricate cosmology. The point is that even when a map is not true to reality it can still be informed by our experience of reality in a way that helps us get closer to truth.

I am also reminded here of Ursula le Guin’s counsel to be realistic differently:

I think hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope. We will need writers who can remember freedom. Poets, visionaries — the realists of a larger reality.

Le Guin was speaking rhetorically, and for emphasis, but as a Science Fiction writer, she knows the challenge of retaining coherence while breathing a larger reality into being. I feel this ‘larger reality’ notion is a useful way to get at the idea of reality as participation in which we don’t just make stuff up, but create within available constraints.

So I am a realist because I believe in a reality beyond human perception and construction. I am an idealist in that I see consciousness and value (and even God) as ontological primaries in relationship to matter (whatever that is) but not reducible to it. I am a pragmatist because I care mostly about what works and helps, and I view social construction as an essential constitutive feature of a participative reality.

I’m not sure what that makes me. A pragmatic idealist of a larger reality?

And that’s how I relate to the role of threeness in general; and systems, souls, and society in particular. I see a key shaped to get into life, informed by knowledge of the world’s lock, and the experience of being a burglar…

**

Once again, why bother with all this?

Here’s why: averting systemic collapse, decontaminating the infosphere, avoiding escalating war and restoring ecological sanity call for cultural transformation. That ‘cultural transformation’ will not be like fireworks and poetry with great background music, but more like a disassembling of the known world and its imperial one-worlding quality. New cultural forms will manifest dynamically in different parts of the world, a pluriverse perhaps, including a fundamental shift in the relationship between the online and offline worlds.

But fine words butter no parsnips. Given our culture’s bondage to surveillance capitalism within an increasingly AI-powered techno-feudal political economy, our last best hope is a withdrawal of consent, not merely from dysfunctional political economies but the social imaginaries that uphold them. And that means metaphysical transgression.

Now, what does that mean? That there is an unsuspected political frontier at the map/territory interface. We, the map readers, who live our lives according to maps made by others are called upon to decide which maps we want not merely to reflect reality but to shape it. We are called upon not to describe reality but to generate it.

The three worlds are not then a conceptual prison that perpetuates delusion, but more like utensils for a metaphysical spring cleaning so that our mental habitat feels more like home - a place from which we can take on the world. This work is in the spirit of Jean Piaget who said that “intelligence organises the world by organising itself”.

I’m just getting going, but since we began with our relationship to reality, I’ll end with something that became real for me because it was read to me by loved ones when I was a child, and remained real when I read it to my children as a parent.

“Real isn't how you are made,' said the Skin Horse. 'It's a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real.'

'Does it hurt?' asked the Rabbit.

'Sometimes,' said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. 'When you are Real you don't mind being hurt.'

'Does it happen all at once, like being wound up,' he asked, 'or bit by bit?'

'It doesn't happen all at once,' said the Skin Horse. 'You become. It takes a long time. That's why it doesn't happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don't matter at all, because once you are Real you can't be ugly, except to people who don't understand.”― Margery Williams Bianco, The Velveteen Rabbit,

Full Series:

However much we Brits like to joke about Americans, I think it’s fair to say that we love you. There is a kindred connection, and your news often feels like our own. What happens in Vegas may stay in Vegas, but what happens in America rarely stays in America. I am sure you don’t need me to tell you this, but it looks a lot like your country is undergoing an attempted coup. The spectacle created by the acquisitive orange one looks increasingly like a deliberate distraction from what the juvenile billionaire is doing, and neither is acting alone. There is always a risk of hysteria and some reasonable doubt, but it’s time to focus.

While it is true that there is a mandate to reduce the size of government, if an unelected figure has acquired the power to stop paying federal employees and the capacity to ‘delete’ government programmes then this is something else; power has moved from an ostensibly legitimate place with rules and conventions to an illegitimate place at the mercy of plutocratic whims. I know that democratic institutions have let people down, but history tells us that things can quickly get worse. If power is still with ‘the people’ in any meaningful sense then it is incumbent on actual people to find a way to mobilise with swift discernment. It looks like four years from now could be too late. I’m not sure what follows for any particular reader trying to get through the day, but Timothy Synder clarifies what’s at stake in Of Course it’s a Coup, and suggests some practical steps in The Logic of Destruction (and how to resist it) including: “Find someone who is doing something you admire, and join in.”

I am grateful to the handful of people who encouraged me to continue this inquiry into the threeness of the world. You make me feel less guilty about potentially alienating everyone else. Sometimes you have to geek out, even at the risk of being inappropriate.

We must not fear jargon when necessary - meta-theory is mostly a way to organise, illuminate and integrate theories. It is a good antidote to the proliferation of listicles of various kinds, which tend to lack metatheoretical foundations. So when you find yourself saying something like: ten reasons the world is falling apart, usually that tenness will be gratuitous and it could just as easily be nine or eleven, which makes it suspect. If you really want to geek out on metatheory, a good place to start is this 2015 paper by Zak Stein. I can also recommend the book A Complex Integral Realist Perspective: Towards A New Axial Vision by Paul Marshall (2017). And then of course there’s the Ken Wilber canon, and if you’re serious you start with Sex, Ecology and Spirituality (1995) where the metatheory is first properly built.

This kind of threeness doesn’t say anything about cosmology or theology, though it doesn’t preclude that, other trios do, and we’ll get to them.

Attentive readers with philosophical antennae will already notice an anomaly here. On the one hand, ‘systems’ does the work of, for instance, Popper’s World I, which is entirely about objective phenomena and does not factor in social phenomena like the economy, never mind ‘economic precarity’. On the other hand ‘systems’ is Wilber’s collective exterior and includes technological infrastructure including AI. It is also possible to take a systems view of the self and even aspects of subjectivity. I won’t resolve this now, but I have thought about it, and will return to these issues in later posts.

This is a map that is clearly necrotic yet somehow lives and shapes our sense of reality. The left-to-right variation in values and opinion is a heuristic extrapolated from the seating arrangements in the French National Assembly in 1791. It is a map derived from a literal territory but from a specific time and place in the French Revolution. This political spectrum found broader application because it was at least intelligible in a world where the individual/collective, market/state and national/international cleavages were driving the conversation. However, that is not today’s world, where neoliberalism (‘the state-led remaking of society on the model of the market’ - Will Davies) co-exists with technofeudalism and/or surveillance capitalism and various strains of nationalism coming from progressive and conservative sentiments; where culture wars are a business model and imperialism is back in fashion, and where putative conservatives tend to want to destroy rather than protect institutions. While all this is happening, ecological breakdown and artificial intelligence are transnational issues apparently beyond our control. In that context the political spectrum functions as a kind of intellectual deadwood, pervasive malware or misinformation - we need something much more elucidating and generative. It will not be easy to stop people using it however until something that clearly works better is created. My organisation Perspectiva is beginning to work on that now and looking for partners and supporters - so it that works intrigues and excites you, please get in touch.

(Reading this late and out of order...) Glad to see your clarity on the brain-deadness of "left-right" analysis. It's something my wife's had to put up with me grumbling about every time it comes up in news reporting. The US is experiencing an autogolpe. Having a better framework than "left-right" to understand it may be critical to its reversal. The plotters have convinced their core followers that the entire humanist and scientific corpus is noting but a "communist" "woke mind virus." Their framing much depends on a "left-right" map that denies a truer comprehension of alignments with the world(s).

Your writing is hard to follow. Lol! But this may be because I don't have any expertise in philosophy. (What even is ontology????) Ultimately, though, I think I get the feel, the gist, of what you are trying to say and maybe that is the most important part. Thanks.