Dancing with a permanent emergency

Why I decided to shift focus from the climate crisis to the meta crisis.

Climate change has been calling me again, and I’m not sure if I should pick up the phone. There are many ways to tell a life story, but an evolving relationship with the largest collective action problem of our time is a new one for me. Between my birth and the age of about thirty-five, I hardly thought about climate change at all. Whatever was happening to the climate was just one of many environmental problems, which was one cluster of societal challenges amongst many, and that kind of framing is still the default for many people today. But between thirty-five and forty I came to understand that we really might be foolish, wayward, and feckless enough to allow our only home to be destroyed in the name of progress. I began to focus on climate change directly as the preeminent problem of our times and it was central to my professional identity. I thought about how to avert climate collapse almost every day and often stayed awake with those thoughts. Yet I soon became frustrated with the prevailing climate praxis. I felt very few people were seeing the tenacity of the problem with sufficient discernment and really grappling with our immunity to change. So for the last six years, I have approached the climate crisis differently, laterally, and almost by stealth, through my work at Perspectiva.1

In what follows I detail how the climate conundrum is showing up for me at the moment, describe and offer links to my professional engagement with climate change, and reflect on how my understanding of the climate crisis led me to the metacrisis, which is my new professional beat. This is a longer post than usual and includes a short climate autobiography, but the ‘joyous struggle’ it discloses is close to my heart and professional purpose, so please bear with me as I try to make sense of it all.2

*

Back in 2016, I gave a talk to a group of international media producers assembled in Stockholm. I began by asking what the following items have in common:

•Cold War military waste in Greenland.

•Surviving a snake bite in rural Myanmar.

•A nine-year-old suing the US Federal Government.

•The value of global pension stocks.

•Corruption in the Maldives.

•The education of girls in the developing world.

•Instant noodles in the UK.

The answer is that they are all climate issues in disguise. The military waste was becoming toxic due to melting ice. There are lots of snakes in rural Myanmar and to have sufficient antivenom you need refrigeration, which means you need affordable electricity in remote areas, which had recently become possible due to developments in solar power. Climate litigation began to take off around this time, and divesting in pensions is a major climate mitigation strategy, as I argued here. The Maldives was receiving climate development aid of various kinds as a low-lying country, but much of it was allegedly siphoned off through corruption. It was argued, from memory by Paul Hawken in the book Drawdown (though I don’t have the book at hand to check) that the single most powerful intervention on climate would be education for girls in the developing world due to the inverse relationship between education and birth rate, and with demographics and growth trends factored in, the seismic knock-on effect on emissions, as well as other positive impacts. Finally, instant noodles use palm oil which causes deforestation and therefore became a target of attack from WWF and other climate campaigners.

These seven examples loosely correspond to the seven dimensions of climate change framework that I developed around this time (science, technology, law, economy, democracy, culture, and behaviour respectively) as outlined further below, but the point of sharing them is to illustrate that climate change is porous and permeating.

There are layers to this realisation, this snowballing awareness that the climate issue somehow swamps the world, not as a tangible thing you can grasp, but as a dizzying notion that is at once everywhere and nowhere, sometimes called a hyperobject. This shift of perspective starts from an awareness that energy extraction and production and consumption drive history and sustain civilisation and there is a direct relationship between energy, emissions, and rising temperatures (Nate Hagens says we are ‘energy blind’) which sounds technical, but energy is therefore implicated in the political demand for rising living standards through economic growth, the culture of consumerism and energy-intensive social practices, including our diets and what follows for the use of land; and all of these matters relate to our prevailing social imaginary and the meaning and purpose of life. Prior to reflection, climate change is an issue over there that environmentalists care about, after reflection, it is implicated in everything, including life in here, in the soul and psyche, in the sense that we begin to see how our customary social expectations are complicit in the global political economy driving the problem we are entangled in.3

And yet, while it’s important to grasp that climate change is about everything, it’s also important to see that not everything is about climate change. Climate collapse is clearly part of the story of our times, and responding to it is part of ‘the plot’ in which we are all characters. However, I believe climate change is more helpfully conceived as a critical part of the setting for our action. As David Wallace Wells puts it, "Everything we do this century will be conducted in the theatre of climate change."

In recent weeks I have felt like I was in that theatre, first as a spectator at panel discussions at St. Ethelburgas and then The South Bank in London. In both cases, the conversation seemed to revolve around the question of whether the right climate strategy is ‘the radical flank’ of groups like Just Stop Oil who believe in non-violent direct action, or ‘the moderate flank’. The moderate flank is now instantiated as the new ‘Climate Majority Project’ that aims to bring people towards a greater appreciation for the need for climate action in a more ecumenical, detailed, practical, professionally relevant, and emotionally engaging way, with fewer demands for moral purity along the way. There is room for both approaches of course, but my sympathies are with the moderate flank because their perspective chimes with my understanding of the challenge.

And I feel the need for strategies again. In the news, I notice the increasingly deadly heat around the world. These stories remind me of the harrowing opening chapter of The Ministry for the Future which features a massive loss of life in Northern India, set in the near future (2025) due to wet bulb temperatures - the combined impact of temperature and humidity that makes it impossible to cool the body down through sweating, and where people struggle to breathe:

Ordinary town in Uttar Pradesh, 6 AM. He looked at his phone: 38 degrees. In Fahrenheit that was - he tapped - 103 degrees. Humidity about 35 percent. The combination was the thing. A few years ago it would have been among the hottest wet-bulb temperatures ever recorded. Now just a Wednesday morning. Wails of dismay cut the air, coming from the rooftop across the street. Cries of distress, a pair of young women leaning over the wall calling down to the street. Someone on the roof was not waking up…With the dawn, people were discovering sleepers in distress, finding those who would never wake up from the long hot night.

So it’s not just rhetorical affectation when the Secretary General of the UN describes the shift from global warming to global boiling because we are on track for wet bulb temperatures in populated areas in the not-too-distant future (though hopefully not as soon as 2025) and they will have major geopolitical effects relating to migration, resource scarcity, and possible war.4

Here in the UK, a desperate Conservative party has decided to effectively abandon any semblance of climate strategy and turn the issue into the basis for a culture war instead, which reminded me of Bruno Latour’s description of this age as ‘The New Climatic Regime’ in which, amongst other things, the politics of climate denial and that policy implications of that still appeals to a large political base. Many countries are now dominated by reality-avoidant cultures. It is simply not true that everyone wants to know the truth. Many millions prefer to live a lie, and many in power will cater to that preference.

So far, so heavy. So what to do?

*

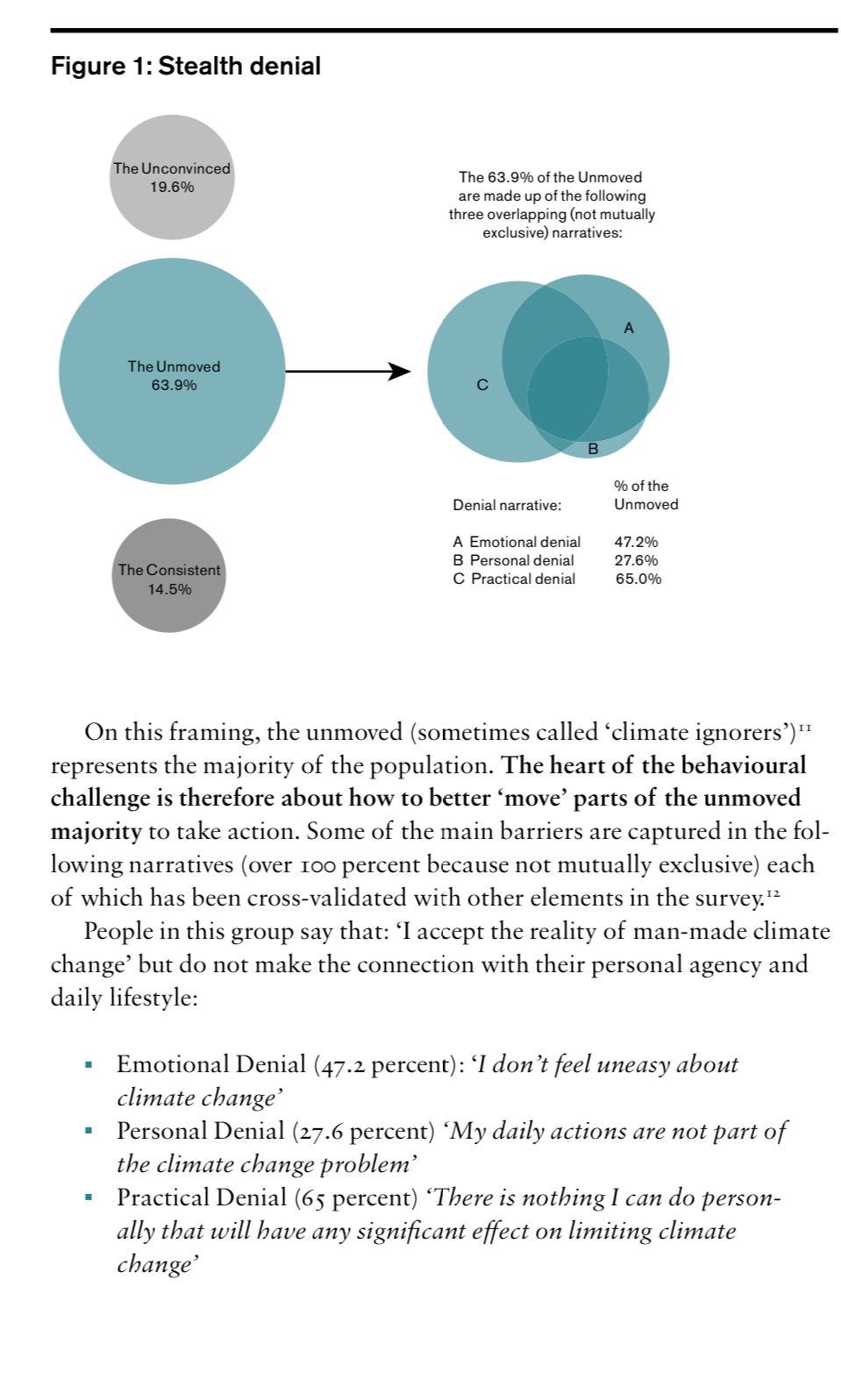

My relationship with climate change began to intensify in a bookshop at The Eden Project in Cornwall in the summer of 2013. I was there on a family holiday, and as a tourist, I was impressed by the domes and all that was inside them, but what mattered most that day was finding The Burning Question by Mike Berners Lee and Duncan Clark on the bookshelf of the souvenir shop. So much of what is best in life stems from finding the right book at the right time. I only had a few months after the holiday to write up an already overdue report at The RSA, which later became A New Agenda on Climate Change: Facing up to stealth denial and winding down on fossil fuels. I had already completed a nationally representative survey designed to make better sense of what it means to accept the reality of climate change but to live no differently as a result, which I called ‘stealth denial’ (see graphic below). Most of the world is in a kind of stealth denial. The report opens with an old Chinese saying: “To know and not to act, is not to know.” Untying that epistemic knot is still the heart of the climate issue.

What The Burning Question did was help me to better connect the behavioural and psychological dimensions of climate change with the geopolitical and technological features of the challenge. Berners-Lee and Clark focus on the idea of humanity’s carbon budget, and the ecological imperative to keep fossil fuels in the ground, but they follow up by considering what makes that quite such a difficult task for an energy-hungry and growth-addicted civilisation. In essence, climate change is a collective action problem with necessary tradeoffs and competing interests and values at multiple different levels of life, politics, economy, and society, including within the individual psyche. Climate change is, therefore, an intensely political issue because the challenge is awash with questions of power, ideology, competing commitments, and struggle. Once you grasp this, calls to merely ‘act!’ on climate change begin to feel obtuse, and a generic call for action is often a sign of someone who has not invested sufficient time to understand what they profess to care about.

In earlier work at the RSA, I had worked on behaviour change and energy efficiency, initially funded by Shell - Cabbies, Costs and Climate Change - and latterly by British Gas - The Power of Curiosity. I am a little embarrassed by these projects now because I think I was complicit in greenwashing, but I was still on a steep learning curve, and both reports have their merits. All this work stemmed from my thought leadership on Transforming Behaviour Change which was a counterpoint to ‘Nudge’ and ‘The Behavioural Insight Team’ that were popular at the time. There’s an overview of my thinking in a Guardian article: Changing Behaviour: How Deep do you want to go? Around this time I had already begun working on the public engagement project called Spirituality, Tools of the Mind, and the Social Brain that would lead to Spiritualise, which can be seen as my advocacy for a kind of deep behaviour change that is not really about behaviour, as such, at all.

What I was learning from my research and professional practice at this time was that my inquiry into climate change and my inquiry into spirituality felt uncannily similar. They were both about encountering reality, and a call to wake up to it, and to know the purpose of our lives better through that encounter. In that context, ‘behaviour change for climate change’ is a vexing issue, if not downright misleading. Climate change is not one context but several (Nora Bateson might call it ‘transcontextual’). Something that appears to work in a specific context (improved energy efficiency of a taxi driver; decoupling of energy from emissions in one country) does not ‘work’ from a larger perspective that acknowledges that contexts are porous and cross-pollinating. For instance, learning to save energy can lead you to use more energy overall due to rebound effects relating to The Jevons Paradox; decoupling is typically relative to units of energy output which depend on contested measurement techniques that involve outsourcing emissions, and so decoupling is rarely absolute, which calls into question whether ‘green growth’ is ever really possible at a meaningful scale. The Burning Question was already wise to all of this and more, and it helped me see the climate question as truly global and multi-dimensional.

This newfound understanding led me to raise funds for the creation of The Seven Dimensions of Climate Change project, which attempted to make the whole issue ‘as simple as possible but not simpler’ and view it as a challenge relating to science, technology, law, economy, democracy, culture and behaviour.

The main purposes of the seven dimensions framing is/was to expand perspective on what ‘climate change’ means, to help people see their own place in it, to help turn a scientific fact into a social fact, to clarify the scope for creative collaboration, and to recognise that the issue is both a technical problem and an adaptive challenge, which is another way of saying that it is everyone’s concern, from the politician to the poet, from from the economist to the educator, from the actuary to the activist, from the innovator to the incense burner. This project began in my own think piece (I don’t write the headlines!) then as a collaborative briefing note with Dr. Adam Corner (detailed in The Guardian) a series of public events at the RSA, including a final event with David Attenborough, and latterly as a report called Money Talks, in which I used my conceptual tool to make the case for divestment in fossil fuels. The opening page of that report arose from a constellations therapy workshop we did with civil society actors on climate change:

Alas, despite the experimentation, the writing, and some innovative events with poetry (text), humour, youth, all seven dimensions together (a tough chairing gig!), and David Attenborough (image below) talking with Tim Flannery (see my question here) I did not notice any discernible change in how people spoke about climate change in public life.

I tried a bit more after leaving the RSA, doing a few workshops on the seven dimensions, a speech at Lancaster University, a day spent ‘in the belly of the beast’ with Shell, and I even had a contract with Palgrave Macmillan to write a book about the seven dimensions, but it never came to pass. I wrote a script for an RSA animation on climate change that was never turned into a film, I was invited to meet leaders at Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute to potentially become an associate there, but it led nowhere. You get the idea, somehow the whole climate thing ran out of steam. Bizarre though it sounds, it felt like the end of a relationship.

Leaving climate change was a necessary and timely move and I don’t regret it, but I miss her at a personal and intellectual level, and I experience the subject matter like a lost love. Although it had its dark and difficult moments, my liaison with climate from 2012-2017 was full of Eros, not in any lude sense of course, but in the sense of the passion of encounter, of connecting with reality, as if at its source.

*

Why do I share this now? Because these autobiographical details help to explain why I perceive the climate challenge not just as an environmental issue, but as a prismatic geopolitical tragedy. The issue is not climate denial in the conventional sense, but monstrous and systemic inertia held in place by culture, power, and convention of what my colleague Ivo Mensch calls our ‘Solipsistic society’.

As Ruth Padel put it at the RSA climate poetry night:

"I am the tragic mask. I am how you defend yourself from what it is catastrophe to have to know."

More recently, reading Alastair Mcintosh’s wonderful book, Riders on the Storm, after he reflects on how difficult and unlikely it is that we can act on climate with the required discernment and speed, I was struck by this line:

“What can one say? What can this dear world do, caught up in the emergent properties of its own predicament?”

Some feel anger towards fossil fuel companies for systematic disinformation campaigns and for politicians for not acting with sufficient resolve, and I can see why. There is a strong case for not making things worse for a start, for instance by cutting down forests or building new fossil fuel infrastructure. Anger is fuel for those kinds of challenges, and we need it, but anger only gets you so far. There are myriad difficult technical, political, and moral questions at the heart of the climate issue, relating to international and intergenerational justice, what we owe future generations, the relationship to colonialism, how much nuclear power we need, what kind of reductions in energy demand are reasonable, or whether ‘energy abundance’ might ever be feasible. It is a vexed problem space, though no less urgent for that, and there is plenty of scope for moral clarity.

*

I believe we should all carry what is ours to carry, to find our work and do it well. I have not yet felt the need to glue myself to railings or to lie in front of traffic to draw attention to the incipient tragedy and disaster of climate collapse, but I don’t find such actions absurd, and I generally admire the commitment of those activists and empathise with their desperation.

I am not an environmentalist by background, and not Pollyannaesque by temperament, but as a chess Grandmaster, I can’t help but notice that the world appears to have played itself into a strategically lost position. There is plenty of noise about climate mitigation, but the upward emissions signal doesn’t significantly change. As I look at the world of nation-states, hegemonic capitalism, energy appetite, competition, and an apparently insatiable drive for material progress, the climate situation looks objectively unpromising, mostly because it looks profoundly stuck. Lots of things are scary about climate change, but what scares me most is systemic inertia. Here is how I put it in Tasting the Pickle:

God knows what we’re doing here, but there’s a real chance we might screw it all up. In fact, it’s looking quite likely. The agents of political hegemony that are invested in the reproduction of the patterns of activity that cause our destructive behaviour might just be conceited and blinkered enough to destroy our only viable habitat beyond repair (The Bastards!). Alas, those who see it coming and watch it unfold might be too irresolute, disorganised, and wayward to stop them (The Idiots!). The regression to societal collapse within the first half of this century is not inevitable, but it’s not an outlier either and may be the default scenario. Are we really condemned to be the idiots who blame the bastards for the world falling apart?

Let’s hope not, and to come back to the chess metaphor, some games are won from strategically lost positions, not just because there is scope to generate counterplay, but because of where the metaphor breaks down.

In the real world, there is scope to change the opponent (whether that is fossil fuel companies, politicians, or ourselves), the goal(we can do so much better than GDP), and the rules of the game (climate litigation) and some of those transformative possibilities are where my work is now focussed.

Through my own formative influences and reflections, I am now convinced that if we want to deal with climate change we need a kind of figure/ground reversal. For decades now climate campaigners have often talked as if the world’s other issues have to be held constant in the background (“We don’t have time to deal with all that”, they say) and climate change must become the key variable in the foreground (“We just have to act! Now!”, they say). This is the framing behind calls for the declaration of climate emergency, which are understandable, but too generic and shrill to shift systemic inertia. Climate change is far more interesting than merely being an emergency, and it deserves better.

One of many ways to see the climate conundrum as distinctive, given that we have known about it for decades now and mostly failed to respond with commensurate resolve is that it is, paradoxically, a permanent emergency, which calls for a different approach (I don’t mean literally permanent, but something more like indefinite, though with some extra shock value required to shift perception). The climate emergency is permanent because the world is warming and will continue to warm for the foreseeable future, and it’s an emergency because the case for urgency doesn’t go away: there are time-sensitivities, tipping points, and cascading effects.

In a permanent emergency, I don’t think deadlines make sense, because every ounce of climate mitigation helps, sooner is always better, and adaptation is always and already necessary (‘Loss and damage’ too, but that’s another story), but you are still trapped. What does make sense in a permanent emergency is to outflank or transcend the context you are stuck in through a fundamental shift in perspective, some kind of renewal of perception, or transformation of human purpose. I don’t see this Utopian but simply as necessary. In terms of our conceptual framing, and therefore our affective response, the context of a permanent emergency helps us to find the controlled urgency, imaginative capacity, and political will to reimagine and refashion the world as a whole.

*

So for a while now I have been a kind of climate activist in disguise, or to use Bayo Akomalafe’s term, a post-activist, no longer writing or speaking about the climate crisis as a stand-alone issue but as the clarion symptom of our broader predicament known as the metacrisis.5 It is a mistake to define the metacrisis too briskly because it is contested, perspectival, discussed from a range of vantage points, and it is alive in all of us, and evolving…but on the other hand, maybe I should get over myself and just define the term?

So here’s the latest version:

The metacrisis is the historically specific threat to truth, beauty, and goodness caused by our persistent misunderstanding, misvaluing, and misappropriating of reality. The metacrisis is the crisis within and between all the world’s major crises, a root cause that is at once singular and plural, a multi-faceted delusion arising from the spiritual and material exhaustion of modernity that permeates the world’s interrelated challenges and manifests institutionally and culturally to the detriment of life on earth.

If that doesn’t seem crystal clear, it’s because it can’t be. The metacrisis term arises as a critique of liberalism in the political theology of Milbank and Pabst, and this version of it is summarised elegantly in a review in The New Statesman by Rowan Williams as “underlying mechanisms that subvert their own logics”; too much liberty makes us less free, too much voting weakens democracy, a fixation with money weakens the economy etc. But that’s only one version. In Daniel Schmachtenberger’s game-theoretic ratiocination and complexity disquisitions, the term is mostly used as a way to get problems in as full a perspective as possible to minimise externalities caused by naive problem-solving, and properly contend with catastrophic risk by understanding underlying ‘generator functions’ like rivalrous dynamics, exponential technology and consuming our ecological substrate. Metacrisis is also used to reaffirm the centrality of education to societal autopoiesis in Zak Stein’s philosophy, particularly with respect to fundamental questions that we need to learn how to ask and answer relating to intelligibility, capability, legitimacy, and meaning; indeed Zak argues forthrightly: Education is the Metacrisis. Although Iain McGilchrist doesn’t use the term metacrisis, his work can be seen as a systematic exploration of it, from our nervous systems to culture at large. In his forthcoming work, Alexander Bard will use the term to mean a simultaneous crisis in Logos, Pathos and Mythos. In Tasting the Pickle, I unpack the ‘multifaceted delusion’ by indicating four main patterns of metacrisis and ten main flavours, though it is ultimately one thing too.

If I could sum it all up in a different way, the metacrisis is about how historical power imbalances, enduring incentive structures, and gradual loss of wisdom in the world system lead to a desacralisation of truth, the implosion of value, an inability to cooperate for the greater good, and demoralisation at scale. This philosophical vantage point of metacrisis has informed my day job at Perspectiva, which I continue to love and which is all about the challenge of the meta-crisis, expressed in our ten premises (see slides at the bottom of the post for more detail and references).6

*

Finally (for now!), a few years ago, after one of many authoritative scientific reports on climate change was released and reported, again, I wrote the following as part of a foreword to a Perspectiva essay.

“Like the famous Sherlock Holmes case of the dog that didn’t bark, the most important message of the 2021 assessment report is that one that is not there. The message that jumps out to me above all others is that previous IPCC reports, going back to 1990, have not been heeded. Where is the report on that? Because that’s the one we really need. Where is the report with IPCC-level rigour and authority that explains the gap between what we know and what we do at scale? Where is the widely reported executive summary that highlights the glaring absence of the pre-political We invoked by scientists? Where is the public awareness campaign on the competing commitments arising from democratic mandates? Where is the world stage where we grapple with endemic corruption that breaches trust, cultural conditioning that binds us to our consumer trance, and targeted technological addiction that keeps us diverted? Where are the daytime television conversations about how fascinating and tragic it is that we get in our way, and what it might take to get out of it?”

And this is where it’s time to end this reflection. It has been said that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism (because capitalism shapes the social imaginary that constrains our imaginative capacity). In a similar spirit, I now believe it’s easier to imagine a complete metanoia for civilisation, a radical shift in perspective on who we are and what life is for than it is to imagine us adequately dealing with climate change within the existing institutional and political framework.

The climate crisis is still there, and it is a moral imperative to address it and it matters perhaps more than any other single issue matters. And yet, because we are so profoundly stuck, I think our best chance, perhaps our only chance, is to see the climate challenge through the prism of the metacrisis, with all that follows for educational and spiritual innovation, which is why that has become my professional focus. Once we realise that there is no way to act on climate change with the requisite skill, insight, legitimacy, and resolve without contending with the metacrisis, our sense of priority should change. There is, as they say, no way round but through.

*I would like to take this chance to thank supporters of my work on climate change, including colleagues at the RSA but especially Trust Executive Sian Ferguson at the Sainsbury Family Charitable Trusts. I would also like to thank the JJ Trust and the Fetzer institute for understanding the shift described above, and for continuing to support Perspectiva’s work on the metacrisis.

The official line is that the organisation is “a collective of expert generalists working on an urgent hundred-year project to improve our understanding of the relationship between systems, souls, and society in theory and practice”. I have tried to explain why we are not a think tank but we do resemble one in some ways, so some call us ‘a soul tank’ as a shorthand. However, I also think of our work as climate activism in disguise.

You may already have noticed an elision between climate change, climate crisis, and climate conundrum. Later I mention climate collapse and climate emergency, and I sometimes just say ‘climate’. In this post, I have not taken great care to distinguish between these terms, though they do mean slightly different things and language matters, so forgive me. It’s just that I grow weary of relying on just one of them, and excessive vigilance with words can take the fun of writing posts like this one.

A particularly striking recent paper in Nature by Lenton et al indicates what’s at stake, by considering the cost of climate collapse in a new way, in terms of the loss of liveable spaces or ‘temperature niches’, which increase gradually throughout the century, with inevitable effects on migration and, possibly, wars. The numbers are expressed in abstract percentages but refer to real lives. When you think of the faces of the hundreds of millions of humans affected, and the fact that it’s already happening and is to some extent inexorable, it should be galvanising. But is it? Even that kind of rigorous science with an innovative frame is still somehow outside the ambit of our direct experience, which is the climate problem writ large.

I was in a private conversation recently where climate collapse was framed by a Hindu nationalist as the genocide of the northern hemisphere (where emissions are highest) over the southern hemisphere (where effects are already intense and will inevitably get worse). Legally, genocide depends on clear targets and intentionality, but morally it can also stem from a kind of wilful systemic neglect, and it’s a challenging provocation. Sadly, this provocation can also be framed, crudely and unhelpfully, but again with rhetorical power, as colonialism redux, with white people killing brown and black people on a massive scale over several decades.

I believe this term is more helpful than ‘polycrisis’ because it explains more, speaks to human interiority, and gives us a better sense of how to act. I have been working on an essay-that-might-be-a-book on this point of terminology, which I think matters, for the last six months, and hope to publish a short version of the case in the next few weeks.

In my forthcoming analysis of the terms polycrisis, permacrisis, and metacrisis, I also consider why almost all theorists of these terms appear to be white men, and what, if anything, follows.

Dear Jonathan,

there is an awful lot of valuable and necessary thinking in your blog entry. It goes very deep and even touches on the need for a "new metaphysics", i.e. a new religious or philosophical foundation, for "civilisational renewal". But if we want to deal with the metacrisis you are talking about it seems to me we need to optimise our thinking through exchange, just as we enhance computing capacity through hooking different computers together. What is missing in your complex analysis from my personal perspective is structure, or "systemic" structure, as one result your complex analysis still lacks simplicity, a "red thread". It also lacks one thing, linguistic simplicity. As I was told many years ago, if we want a better world we must aim to write so everyone understands (this does not mean that I achieve this necessarily).

What we agree on is the fact that we (humanity) has many problems, the most urgent and pressing one appears to be the Climate Crisis. One key question is whether it is solvable at all. You speak of global systemic inertia. Stephen Hawking suggested in 2016 that in order to solve the many problems humanity is facing "With resources increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few, we are going to have to learn to share far more than at present", and "more than at any time in our history, our species needs to work together". This means in my understanding, humanity has to overcome its inherent egotism and bounded rationality, if it wants to survive. Can "we" achieve that at all? It might seem impossible. If we were to answer the question concerning the solvability of our "metacrisis" still with "yes", then the question arises, how do we solve the problem? In your blog entry you speak about "naive" problem solving. But whichever way you turn it, we seem to have severe "problems to solve", of different kinds, and largely interconnected. That appears to be a reality which we cannot deny. The question then is, how do we solve a complex problem? Since our own thinking is possibly limited and faulty, it makes sense to test it and guide it through problem solving methodologies. Systemic problem solving methodology is useful and perhaps necessary to identify the logical connections between the many aspects you mention in your blog. Once we understand, how everything is connected we can then possibly answer the question how to set an effective problem solving process into motion. One issue which systemic thinking suggests is that an organism requires leadership, a driver to solve problems. I plan to have an exploratory debate in September on what we might still be able to do to stop the Climate Crisis even at the advanced stage of global warming we are in. https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/exploratory-debate-how-to-stop-the-climate-crisis-tickets-681550504907?aff=ebdssbdestsearch. Why not check out what a systemic approach might offer for the solution of the various interconnected problems? Are the problems solvable at all? Is human nature in the way? If, yes, what must an effective approach look like to solving the various issues connected with the climate and the metacrisis you are talking about? I would greatly appreciate discussing these issues with you and the other participants in the meeting. Hans Peter Ulrich

The gas chamber is manned by a technician whose only paid job is to keep the machine running and take care of the killing machine.

Even on dissolution, the job seeker can only have a career of manning the machine as a marriage has been performed by the patriarchal arrangement of service to the world at any cost.

Unschooling is to dismember the career and seek therapy of community, away from individualism.