Forgive yourself for speaking on behalf of the world

Why it would help if we stopped referring to we as if we knew what we meant, but it's not clear if we can.

Here are three things that I think might be connected:1

The intractability of collective action problems, especially climate collapse.

The preeminence of English as the world’s Lingua Franca, especially online.

In English, ‘we’ is almost infinitely ambiguous. Our language is fairly unusual in not having ‘clusivity’ i.e. the distinction between the inclusive first person plural pronoun, We, and the exclusive first person plural pronoun, We, can only be established by context.

On the first point, here’s my reflection on working on the climate crisis and the metacrisis which explains why we are so stuck and apparently unable to deal with the climate crisis. This current post inquires into one key feature of our stuckness, which is our confusion about collective agency at a planetary level and our incapacity to solve a variety of coordination problems.

The second point is empirical in that we know there are roughly 1.5 billion English speakers, followed closely by Mandarin, Hindi, and Spanish. But the power of English goes beyond mere numbers. The English language remains preeminent for historical (colonial) reasons, and it has become the language of international business, the internet, international treaty negotiations, and popular movies and songs.

The third point is more complex, and my focus here. The general point about ‘we’ being ambiguous does not require linguistic scholarship, but there might be something significant about the structure of the English language that makes it poorly suited to addressing today’s pervasive collective action challenges. Clusivity is a grammatical distinction between inclusive and exclusive first-person pronouns - also called inclusive we and exclusive we. Our inclusive we specifically includes whoever is being addressed, while an exclusive we specifically excludes the addressee. This means English effectively has two (or more) words that both translate to we, one meaning ‘you and me, and maybe someone else’, the other means ‘me and some other or others, but not you’. So ‘we need some time together’ could be the inclusive we in action used to make sense of a family agreeing to go on a trip with another family, but ‘we need some time together’ could also be a reason for the exclusive we to say no, meaning the family prefers to focus on itself.2

One of the main reasons this lack of clusivity matters is that it leads us, somewhat absurdly, to speak on behalf of the world. “We need to transform the global economy”, “We need to reduce the disparity in prosperity between the developed and developing worlds.” “We need to prevent AI from getting out of control.” This issue used to bother me, but I think it’s OK if you are aware of it, because it’s very hard to avoid without sounding ridiculous. As I say in the title: forgive yourself for speaking on behalf of the world, and perhaps laugh at yourself too.

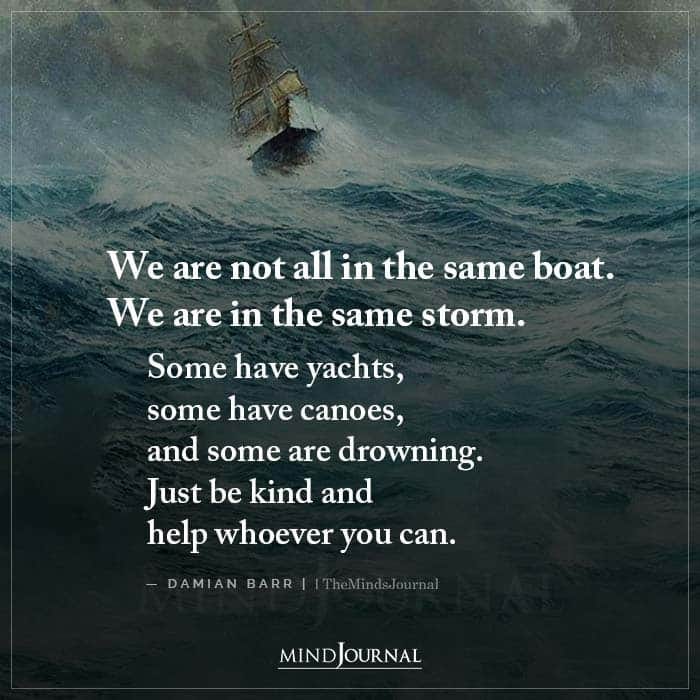

But notice what’s going on. A simple statement by Damian Barr elegantly highlights the problematic nature of the elision between the inclusive and the exclusive we.

We are not all in the same boat (the inclusive we does not apply). We are in the same storm (the inclusive we applies). Some have yachts (‘we have yachts’ is an exclusive we).

There is a deeper and related problem, which is that the promiscuous nature of the inclusive we leads us to conflate different kinds of challenges. Climate collapse is ‘caused by humans’ which means ‘we’ caused it, but that inclusive we is not who is really responsible. For instance, a study by Climate Majors in 2017 found that just 100 companies are responsible for 71% of global emissions (there may be an updated study or a sharper way to make this point). If those 100 companies were to speak from their exclusive we, they could claim responsibility and act upon it, but instead ‘we’ - not ‘them’, feel obliged to address it. It’s never that simple, because there is some complicity in our engagement with these companies, but the underlying point is sound.

‘Humanity’ is rarely a meaningful unit of collective agency, so the inclusive we is typically off the mark, but we can only specify an exclusive we by getting political, which means moving from ‘all of us’ to more specific and contested moral demands.

Could it really be that the problems we think of as economic or political or epistemic or technological or spiritual may all in some fundamental sense be problems of our grammar too? I am beginning to wonder. One of the main reasons we are struggling to make sense of our plight is because we are obliged to invoke a we that does not really exist, and talking as if it does evokes widespread dissonance, which saps morale.

What a predicament. Our collective fate depends on a collective that is not really there. I believe this kind of problem may be a good illustration of the mental/rational mode of consciousness entering its deficient phase, and it highlights the ‘irruption’ of relatively efficient aperspectival ways of knowing that visionaries like Jean Gebser prophesised; views of the world where ‘I’ and ‘We’ and ‘You’ and ‘They’ are altogether more co-arising and entangled (see ‘wewho’ below).

With those thoughts in mind, consider the following statements and ask yourself if they are inclusive or exclusive or in some interesting sense both.

Gens Una Sumus - Latin Motto (We are one people)

We the people of the United States… (First line of US Constitution)

We will fight them on the beaches. - Winston Churchill.

We are the first generation to feel the impact of climate change and the last to be able to do anything about it. - Barack Obama

We children are doing this to wake you adults up. - Greta Thunberg

The point of sharing these examples is to show that unless we stop to think about it, we barely notice the different ways we is being used, and the inherent ambiguity of the term is part of our predicament. It helps to realise that an inclusive, democratic we (we the people) and global we (humankind) is presupposed in questions like:

· What do we need to do to address climate change?

· How might we save democracy from itself?

· How can we guide technological innovation in a way that benefits everyone?

This kind of language is innocent enough, but it is also powerless. The mostly unreflective way we use ‘we’ in our discussions of societal direction very often ignores localised conundrums, varying perceptions, competing interests, and power dynamics and thereby obscures the nature of the work that needs to be done.

I believe a figure/ground reversal is called for, in which there is a shift from assuming our collective perception, understanding, and interests of the world are a stable vantage point; while the figure or situation we look at together is what remains in question.

I think the challenge is the other way around, namely to immerse ourselves in our predicament in such a way that we see the We in question more clearly, and to prioritise acting on that (This is partly what I mean in Perspectiva’s ten premises by ‘democratising hyperagency’).

· How might the reality of incipient climate collapse be conceived and acted upon in ways that help us transform the We that has failed to prevent it?

· How might the institutions and norms of democracy be strengthened in ways that help to forge a We that is worthy of the ideal and not one that is destroying it?

· How might technology best be designed, owned, regulated, and perhaps even in some fundamental sense dethroned, to foster the kind of We that makes a good society possible?

Better, no? These feel more like generative questions to me.

The main limitation of the idea that we face a climate emergency is that there is no ‘we’ as such to address it. The We that wants to say there is an emergency is not the same We as the We that needs to hear it, and the We that needs to hear it has several different ideas about the nature of the We that should do something about it.

More generally, there are competing tribes, perspectives, interests, and factions in the world, and perhaps there always will be. Spending time in Sarajevo as part of my Open Society Fellowship was particularly useful, because it revealed how easily and tragically war can arise when a collective sense of We-ness shatters into lethal shards of them and us. At almost every level of analysis, from sclerotic global governance to quarreling spouses, we appear to lack sanctified mechanisms to resolve what kind of We we want ourselves to be.

Perhaps spiritually we are one, or could be, but politically we are many, indeed for many how we decide to demarcate our ‘we’ is the fault line of politics. As the infamous Nazi jurist and theorist Carl Schmitt put it in The Concept of the Political: “Tell me who your enemy is, and I will tell you who you are.”

That idea risks turning toxic, but our ‘enemy’ can be relatively conceptual like ‘greed’ or ‘capitalism’ or ‘delusion’ or ‘the metacrisis’, and since politics is about our felt sense of the operative collective, it is worth thinking about what we want from We.

The appropriate scale for ‘we’ as a unit of action is the critical question, and it’s an urgent one too, at a time of global collective action problems where the presumptive global we is clearly not a viable unit of action. I felt the acuity of this point in a personal exchange with Dougald Hine. Whenever people travel and converge for conferences of various kinds, he said, the question invariably arises: ‘What should we do?’ And yet there is usually no ‘we’ in the room that is capable of coordinated action because they are all away from their contexts and networks where each of them may more readily establish units of action, and that recurring confusion wastes precious time. Perhaps the advice is simply to think about what ‘we’ means to you, and find your viable units of action.

To take an example at a larger scale, we need to keep most oil and gas reserves in the ground and virtually all coal in the ground to give us a fighting chance of staying within the relatively ambitious 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures. There’s a compelling case for pursuing that global objective if you are one of the thousands of inhabitants of Tuvalu or any other low-lying small island state with non-amphibious humans who simply wish to live above water. However, if your political remit is to do something about energy poverty affecting millions of families in a coal-rich part of rural India or China, you may see things differently. Likewise, if you are one of many rapidly developing African countries seeking to catch up with Western living standards and you notice that a lack of an international airport places you at an economic disadvantage, it won’t look obvious that ‘we’ shouldn’t build any more airports.

The careless use of We matters because too many progressive visions of the future are premised on heroic assumptions about widespread cooperation and shared interests aligning at scale.

I am not sure what follows, only that our idea of ‘we should’ is vexing.

There is abundant goodwill and ingenuity in the world, no doubt, and I believe in giving our better natures every possible chance. Still, the only pathways to a viable future for humanity that seem credible to me now are those that acknowledge the enduring realities of self-interest, competition, conflict, defection, and corruption. The core problem is the absence of any locus of shared power to generate cultural sensibility and policy coordination commensurate with our collective action challenges and to see them through in the context of widespread political divergence and resistance. That indicates a different pattern entirely may have to emerge, but for that to happen the words we use will have to pre-figure it better than they do today. The climate majority project appears to be moving in that direction, but I feel the problem is deeper somehow, and also deep within the metacrisis I covered last time.

In subsequent posts, I plan to detail some proposed solutions to the problem of our wayward we-ness, including the idea of collective individuation as a way to see the co-arising of I and We more clearly, and also the notion of fractal agency which is about how to contend with the challenge of scale without presuming a global We.

For now, I am only half-joking when I suggest we start thinking in the language of ‘Wewho?’ - a more dynamic and hybrid form of collective identification that functions as a living question. I am grateful to Minna Salami for suggesting this coinage to me as an alternative framing, as in “Wewho have to act urgently on climate change!” (with or without the question mark and/or the capitalisation, I’m not sure…). I recently gave Minna the term ‘epistemic polyamory’ for her work, meaning the love of multiple ways of knowing, so I trust she won’t mind if I use Wewho for mine. It seems like a fair trade!

Clearly Wewho have more to discuss on this matter, but that’s all I’ve got for now.

This post is an original piece of work with several new ideas, but it builds on borrows from some prior material in my essays: Tasting the Pickle and The Impossible We.

I am not a linguist, and I look forward to investigating the technicalities of the issue further when time allows. For now, I just made a small recurring donation to Wikipedia, and I am sharing the following from there. This is merely the start of this aspect of the inquiry, but if any readers are linguists I would love to learn more.

“ in some fundamental sense be problems of our grammar too?”

I suspect so too. Hearing calls for a more relational, or even fundamentally relational onto-epistemology, I wonder just how well the subject-object grammar of English supports such a Weltanschauung?

OK, so "we" might be problematic, but in some languages like Japanese, the subject of a sentence is entirely omitted and understood only by context and guessing.

I wonder if there's a different axis to "we" than just the clusivity one. Perhaps it is presumptuous to speak for the whole world, but I find it problematic to speak only for my "self" as well. Like Whitman, we all contain multitudes, often echoing voices and cries from the past that either haven't been heard, or which we don't know [how] to dampen.

There is real reason for the vague we. We can venture away from it, but it takes a lot of skill and courage to start suggesting specific responsibility in a climate charged with as much emotion as carbon.