The Opposite of Transformative is Intelligible

Davos, Hyper-agency, and responsibility for the power to create context.

My step father, Ray, just turned 84. Happy Birthday Ray! That number resonates because it’s the mirror image of my own age. This post is dedicated to Ray, and all our kitchen table conversations over the years, many of which have begun with him telling me about the “terrific article” he just read. I hope this might be a “terrific article” too.

I was once asked what I would say in a speech to world leaders, given the chance. I thought about the question for several months and realised I had nothing to say that would make a difference. I know that sounds defeatist, or even like learnt helplessness, but it felt more like a revelation, and a clarification of the work that is mine to do. If I were to speak well I would get applause, and I may even be able to seed an idea or two, but those ideas live amidst thousands of cannibalistic ideas that are out to hunt, eat and metabolise other ideas for other ends. So while charm, intensity and information might seem worthwhile, the available arena does not give rise to the agency we need.

This thought is coming back to mind now because elites of various kinds - political, financial, business, technological, and cultural - will soon be meeting at the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, which takes place this year from 19-23 January. I have never been to Davos, and the ideas I want to develop here applies beyond an annual gathering in the Swiss Alps, but it’s a good focal point.

Generative networking and consequential conversations will arise in the mountains, and this year I know a few people personally who will be working behind the scenes to literally speak truth to power, and mostly not on stage; but relatively quietly, over food, and on walks in the crisp air. I don’t mean to imply that the whole gathering is a waste of time, nor that it’s a mistake to want to be there, only that I don’t place my personal faith in it, or feel drawn to attend.

There are some theories of change that say getting the ear of the elites is the sine qua non of changing the world for the better, but that’s not my understanding or experience. I am still broadly of the view that enduring and meaningful change requires coordinate action across systems, souls, and society, and therefore the effective coordination of top-down, bottom-up, side-to-side, and inside-out approaches to succeed. As I argued here, you need Elites, yes, but you also need incentives, solidarity, the right kinds of fatalism, and of course a generous helping of love.

So why do I feel I have nothing to say to global elites that would help?

When I ask myself what the opposite of transformative might be, I find that the best answer is not informative, or pedestrian, or modest. The best answer is intelligible, and I would like to try to explain why. There’s no typo here. I don’t mean ‘unintelligible’. I mean a prerequiste for transformative work is not being widely understood.

I don’t think what is mine to say is intelligible to most of the people attending; not because they are not smart, but in a non-trivial sense they are living in a different world and speaking a different language. My impression is that Davos is a costume party for power where leaders arrive dressed in the language of urgency while structurally preserving delay. The alpine luxury is a perfect symbol for how power protect itself, inaccessble and socially insulated, mirroring how decision-makers remain buffered from the pain of the world.

The basic insight is perennial. People listen through conditioning and vested interests. Whether it is Goethe: “we only hear what we understand” or Anaïs Nin: “We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are” or Upton Sinclair’s “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it”, the idea is that an audience is not an empty vessel for you to fill. Nietzsche, no less, says that we have no ears for what experience has given us no acccess. Another way of putting that is that a speaker has to be audible on the audience’s frequency and legible to the audience’s literacy.

An audience it is more like a congregation of somewhat flexible shapes with their own contours that your words have to bend in the right ways to find their ways into, and those contours grasp over meaning, so sometimes you are in a race for your ideas to find an unassailable place in the shapes of other selves, before being denatured or coopted, or simply rejected because you don’t fit. When David Bohm says: “Thought creates divisions out of itself and then tries to bridge them” he is getting at this kind of idea. As I understand it, and sometimes experience it: X speaks A, and if Y has never heard A he hears B and listens from B, then when X develops the idea with A1, Y will hear B2 and before you know it you are trying to connect over the relationship of, say, A5 with B4 (it sounds like chess, I know) and both parties are none the wiser.

**

There have been some dramatic speech moments in recent years. Greta Thunberg’s “How Dare You?” speech to the UN in 2019 comes to mind, as does Mia Mottley’s declaration that “national solutions to global problems do not work.” Maria Ressa’s “An invisible atom bomb has exploded inside our information system.” And then there are Rutger Bergam’s “Why is nobody talking about taxes?” (at Davos) Zelensky’s “We are here” after the Russian invasion, and Arundhati Roy’s “I refuse to play the condemnation game” at her PEN prize acceptance speech, in the context of genocide in Gaza.

I found all of these speech acts impressive in different ways, and they have all been shared widely and will have had a range of effects on people and the systems they are embedded within, but have these ‘big moments’ led to meaningful shifts in terms of actions that speak to what Power cares about and where it is going? I don’t think so, and while there are many ways to explain why, I have my own framing of it.

There is a scene from an old Hollywood blockbuster - Independence Day - that helps to illuminate the issue by analogy. The clip is probably worth five minutes of your time, but if you can’t bear it, the scene concerns deactivating an alien vessel’s forcefield to enable that same vessel, previously captured by humans, to board the alien mothership, to access its system and remove its shields long enough for human fighter planes to approach and destroy it.

It’s not high culture, but the underlying ideas are important: When there is no apparent way forward, our primary task is to overcome resistance to requisite action. Or, if we want anything meaningful to change, we have to overcome what we see as the source of the immunity to change. Moreover, the clip also suggests, albeit in a dramatised way, that it’s sometimes worth expending extraordinary energy to merely create opportunity, even for uncertain rewards. The long shot is sometimes the best and only shot.

I have used some version of this clip in public talks because it helps to disclose what is called for today, and what has been called for for decades. Audiences tend to get it, but it is less clear that the Davos crowd in aggregate would get it because they would imagine themselves as the mothership, but they are more like the captured alien spacecraft that needs to be given a virus so that the forcefields drop and the requisite information and energy can get through.

**

I am grateful to Bayo Akomolafe, whom I was glad to spend some time with earlier this year at Naduve, for his repeated emphasis on the importance of being illegible. To be legible is to be readable, predictable, controllable, sortable, categorisable, repeatable etc. To be illegible is to be relatively free from those forces that shape the world. And yet, if we are not careful, being illegible may also mean being lonely and irrelevant, unable to take part in the conversation of humankind. So the challenge is to find a way to be illegible in a way that is helpful and inviting, such that our audiences are drawn by our language and seek to learn to speak it and relate to us and others through it. On reflection, it’s more like a dialect than a language. Even if we speak the same language, we all have conceptual dialects, and I guess the challenge is to figh to keep them alive, to resist the assimilation into the generic common tongue.

There is close connection between legibility and intelligibility. I have been quoting a line of Richard Rorty’s for several years now, but only recently did I grasp what it means.

The chief instrument of cultural change is not arguing well but speaking differently.

There are many ways to speak differently, but if we are entirely intelligible, the chances are that we are merely adding to the information of the world, not transforming it. I think speech that is truly different has to be at least somewhat unintelligible, such that it goes beyond our existing frames and concepts, and moreover to do transformative work may entail almost by definition that we are not intelligible.

Anyone with any kind of progressive sensibility wants to be transformative, and I believe in the intellectual dignity of that term. ‘Transformative’ is definitely overused, but if ‘trans’ is a kind of migration, about going across, through, over or beyond, all that is needed is a conception of ‘form’, and an idea of what it means to move through and beyond it. In an educational context, ‘form’ might refer to the assimilation/accomodation/equilibrium process that Piaget sees as the basis of the learning organism, updated in Robert Kegan’s ‘subject-object relationship’ that shapes perception and the interplay between self, other and world. But the form in question can also be ‘the system’, ‘the paradigm’, ‘the imaginary’, ‘the sacred canopy’, or, even deeper, as my colleague Ivo would put it, our ‘priors’.

The cultural change called for today has to be transformative in that sense of moving beyond the forms perpetuate culture, which is why artists like Ben Okri call for ‘existential creativity’. Do we grasp that cultural change is now literally a matter of life and death? Do we see that the life we know and love is only possible on an utterly precious and possibly uniquely life-giving planet under conditions of freedom, but that our culture is creating an increasingly ecologically depleted, badly governed and incerasingly under surveillance and algorithmic control?

Mostly no, I don’t think we do. And I feel that if language is not transformed, it can’t be transformative.

I felt this way a couple of years ago, on reading Ayisha Siddiqa’s celebrated poem about climate change, which includes the line:

The future frolics about, promised to no one, as is her right.

I found so much hope and solace and inspiration in that poetic turn of phrase, but I also know live in a world of ‘Take Back Control’ and ‘Make America Great Again’.

**

So it’s not that I have nothing to say. In fact, my view of the world is crystallising and I’m eager to share it. In Perspectivan language, the setting is the metacrisis, the protagonist, humanity as a whole, is at odds with itself; the antagonist is the wicked H2minus vortex, and the plot is about the flip, the formation, and the fun. The story of our time is quite clear (to me!) but my message for the world is conceptually mediated because we need different forms of language to shift perception and understanding. I know it’s a problem that the langauge is conceptually mediated, and I feel I can and must do better, but it’s not about being more ‘accessible’ - it’s more about shaping culture in a way that being unintelligible is not always a failure, but often a necessary attempt to make a kind of sense that hasn’t been made before.

If I state my case in plain language, it sounds cliched: Planet Earth is an utterly precious place and humanity is in the midst of an epic struggle to survive itself, our perception of reality has become distorted over time, and our understanding of the meaning of life needs reparitive attention; we need to work together better to find collective agency that is worthy of our challenges, whenever we try to change something we should first be honest with ourselves about what we don’t want to change, we need to stop the present relying on the past to shape the future, we need a critical mass of people to experience the world differently, we need education for the soul as an international priority, we need to build a political mandate for a prosperous society that does not depend on indefinite and ubiquitous economic growth. Oh, and our problem is that we don’t really know what ‘we’ means. But peace would be good.

If that sounds platitudinous, it’s because in plain language the amplitude and specificity of the ideas is lost. For instance, the species as a whole is mostly surviving and status-seeking, but for those interested in the planetary problematic, our challenge is not a polycrisis, but a metacrisis; that distinction matters, as I’ve argued before, because the main pathogen in the global body politic is not complexity, but delusion. And yet, I am not sure Davos knows what to do with the idea of delusion.

**

A final thought, on the challenge of feeling unintelligible in a world shaped not just by ‘culture’ but by power.

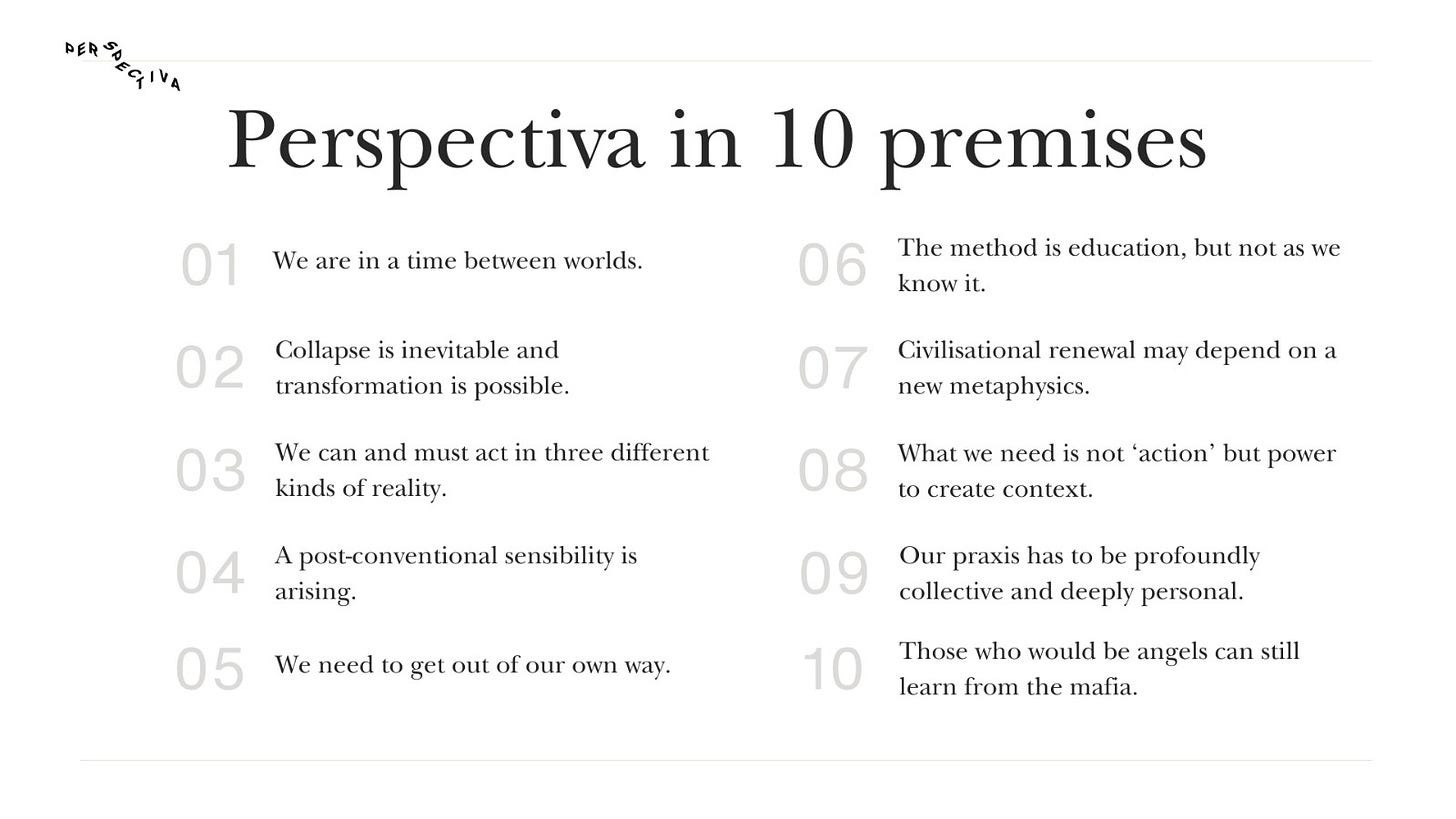

Perspectiva’s eighth of ten premises is that what we need is not ‘action’ but the power to create context, and the critical idea here is the distinction between agency and hyper-agency.

What matters most today is not merely being able to change the world but to change how it changes. If agency is the capacity to make choices within conventional social processes, hyper-agency is the capacity to be a creator or producer of those processes. Philanthropists have this power in theory, but don’t always use it well. At its most successful, around April 2019, Extinction Rebellion showed signs of a more inclusive and solidaristic hyper-agency, but it fell apart. To change systems the emphasis is on the creation and better mobilisation of hyper-agency, which is about the capacity to shape circumstances and contexts rather than merely acting within them. For instance, agency can improve an underperforming school, but hyperagency can create a new school system with a new curriculum. In a famous study of philanthropy, Paul G. Schervish and Andrew Herman, 1988, describe hyperagency as:

The social capacity to create rather than simply work within the institutionally given world...the capacity to exercise what we call hyperagency – the ability to exercise effective control over the conditions and circumstances of life rather than merely living within them.

The challenge is to somehow democratise hyperagency, so that is not merely something available to Tech Billionaires and heads of large states meeting at Davos. Democratising hyperagency is not the same as merely trusting the state, however, but about resisting whatever is given as being the default form of life, and that includes forms of technology including AI, but also the language we use. It means a willingness to be both illegible and unintellgible, at least in certain contexts.

I really don’t know how humanity writ large wrestles hyperagency away from the elites, but I see my role in that process as attemtping a kind of field creation, growing coordination within a larger domain of inquiry and practice among those who share a post-conventional sensibility, for instance with a collective funding process, targeting philanthropists and impact investors who have the power to begin addressing the meta-crisis and supporting it institutionally and culturally.

So there is a need to speak well about things that matter in new ways. Applause is welcome, but the work that needs to be done asks for much more than applause. Inspiration and action are related of course, but they are further apart than we are typically led to believe, and there are other variables too, not least identites premised on being right and good, and the balance of power in the world remaining as it is.

It is noteworthy that in Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, one of our better novels about contending with the climate crisis, the world leaders at Davos are selectively kidnapped, with the protagonists arguing this was necessary to get their attention and shift their sense of priorities. Now, for the record, *I am definitely not advocating this strategy*, but the hermeneutics of it are spectacular. Robinson is saying: you can’t just keep talking as if that’s going to change the direction of travel.

With some notable exceptions, the worldview of the financial and technocratic elite seems impervious to the transformation in perspective and praxis that now seems necessary to avert the great unravelling, by which I mean a mixture of ecological collapse and war. My heart tells me that other possible futures are not so bleak, but viable and desirable futures are outliers, and not readily achievable in the context of the hegemonic worldview we have today and the delusions and concentrations of power that characterise it.

Niches of alternative sensibilities abound, and there is plenty of hope if hope’s your thing. Yet if we are, as Clifford Geertz once put it “Animals suspended in webs of significance that we ourselves have spun”, then it’s not so easy. It’s no wonder we struggle not to think through our inherited and encultured faith in reason, science, progress, and our orientation towards the future. Modernity has been weaving its web through our psyches for hundreds of years.

We should be kind to ourselves. It is no wonder that we struggle to remain open to the possibility that our sense of normal life might destroy the world we love. This is impossible knowledge. So we deny it. The poet Ruth Padel captured the spirit of this impossible knowledge in a climate poetry night I was involved in:

“I am the tragic mask. I am how you defend yourself from what it is catastrophe to have to know.”

**

I could offer the Davos crowd some tasty intellectual candy to make plausible nightmare scenarios palatable. Perhaps I could wax lyrical about the need for a global Bildung movement, or I could say something about the need to realise that this one world is also three worlds in disguise - systems, souls and society. Yet most of what I could say would bounce off professional shields and epistemic force fields, just like the alien spacecraft. And whichever ideas made it through the first line of defence would soon be denatured and absorbed by state and market logic, and electoral calculus.

What is called for in our world leaders is something more like metanoia - a transformation of heart and mind, renewed perception and valueception, and through that spiritual shift (‘the flip’) a change of political priorities. Some would say that’s naively idealistic, and it’s hard to disagree. The challenge is then to minimise harm in the short term with existing institutions and sensibilities (including law) while also forging a movement that can take on that transformative task across global civil society. That means new forms of collective agency informed by a transformation of perspective and wiser priorities. But how do we even begin to get there?

I don’t know, but perhaps we need to kidnap ourselves, and ask for creative power as our ransom demand, the kind we can only get by giving.

I enjoyed reading this mate. It’s taken me a few days to sit on it and I’m reminded of an idea from Ron Heifetz one of Bob Kegan’s pals who talk about the ‘zone of productive disequilibrium’. What I’m sensing from this essay (and I actually liked the one or two typos– it felt mercifully human) is a ‘zone of productive unintelligiblity’.

So, when you quote Rorty on “speaking differently” I get back to something I inadvertently raised with you: axial shifting. You can’t whack the orb entirely off course, but a transformation is possible from a shifted angle of spin.

Ed Sanders, beat poet and Fug, had a favorite line from Plato:

'When the mode of the music changes, the walls of the city shake.'

Bit like your Rorty quote on 'The chief instrument of cultural change'.