Are you Clumsy Enough to Succeed?

Top-down. Bottom-up. Side-to-side. Inside-out. (The Hokey Cokey is optional...)

I don’t plan to write about Lough Neagh again for a while, but doing so last week got me thinking about “clumsy solutions” to complex problems. Clumsy solutions are multi-faceted approaches called for in vexing situations, and they are contrasted with ‘elegant solutions’ that typically only work with relatively simple problems.1

In a few days, my interview with Nate Hagens will be online, and as part of his research, he shared with me an article I wrote on 09 Apr 2014 that I had forgotten about. I’ve edited and updated it below and added a few reflections on the main model that informs the idea of clumsy solutions, often called Cultural Theory.

The next time somebody tells you that we need to move beyond 'top-down' solutions and do things 'bottom-up', ask them which way is North on their compass - where are they exactly, and where are they trying to go?

The point is not to disorient anyone, although that can be fun, but to get beyond cliches, think harder about what matters, and resist the stubborn persistence of lazy distinctions.

There is nothing inherently wrong with 'top-down'. There's a time and place for authority, hierarchy and regulation, which is often needed to resolve intractable debates or create impact at scale. However, that kind of authority must be democratised and contained with suitable checks and balances.

And there is nothing inherently right about 'bottom-up', because while there is also a time and place for context, specificity, granularity, and the passion that comes from particular people fighting for particular purposes in particular places, there is a limit to what you can achieve without the major levers or macroeconomic and geopolitical power.

The deeper problem is that this geometric juxtaposition feels cliche-ridden because it is two-dimensional, 'flatland' view of the world and the power that lies within it.

As Cultural theorists have highlighted before, forms of social change are manifold, and often in tension, so while there is a bias in progressive circles towards 'bottom-up' approaches, I find the following four-part structure useful, not least because it highlights the importance of the deeper forms of behaviour change that have defined my work over the years. (There are also some overlaps between Perspectiva’s emphasis on the relationship between systems, souls and society being the operative active ingredient that matters most.)

We need to use all available tools. We need the vitality of personal agency, the systemic impact of smart regulation, the elegance of socio-technical innovation. But we also need the discernment to keep ourselves present, open, aware, connected, vulnerable and inquisitive as the whole thing unfolds. Here’s a rough sketch of what that means:

1. Top-down (Political change for challenges relating to social and economic structure)

Key features: Impact at scale, usually involuntary, often relies on policy influence followed by regulatory change.

Regulation gets a hard time, but it is sometimes necessary to create change at scale. The major changes needed to break down some of the barriers that currently constrain us might include:

Challenging the legal status of corporations as persons, which arguably gives big business far greater legal protections than they deserve.

Working with the Law Society to shift fiduciary duties, so that companies can fulfil their legal obligations to shareholders while also factoring in the long-term viability of the business, that would make it much easier to be genuinely sustainable.

Introducing a basic income for everybody in the population to strengthen the core economy based on care and trust, and mitigate the risks that prevent many from starting their own business. In case this sounds ‘loony left’, it’s worth knowing that Hayek supported this idea.

Campaigning on land reform. Coming from Scotland, the law of trespass in English law seems cruel, and the freeholder/leaseholder divide on many properties in England strikes me as feudal; such constraints get in the way of various forms of community action and people using their properties in creative ways, for instance, to create or store their own energy.

2. Bottom-up (Social change for challenges relating to tangible and specific issues of a civil, civic or ecological nature)

Key features: Specific and contextual, usually voluntary but often need-driven and stemming from individuals or small groups, often tied to particular places or domains.

Such top-down changes don't prevent bottom-up changes; if anything their purpose should be to facilitate and encourage them. Local context is not a noise obscuring an underlying Platonic political form, but the very lifeblood of what matters to most people. Recycling, for instance, is about global resource constraints; but for many it's about orange council bags under the sink or blue boxes out in the street.

If we need a reconceptualisation of agency, that means motivating people to act, which means seeing how the macro manifests at a micro level in our lived experience and starting from there. Paul Hawken's classic book 'Blessed Unrest' about the rise of social movements gives an excellent overview of this kind of power.

3. Side-to-side (Change stemming from socio-technical disruption, characterised by systemic innovation)

Key features: Change that stems from loose associations of values and interests across domains, usually disruptive or entrepreneurial in spirit, grounded in virtual networks, now pervasive and international due to social media.

What the conventional idea of 'bottom-up' change doesn't capture is the significance of what Jeremy Rifkind calls lateral power and the growth in 'disintermediation' - people can get things done by themselves or with other like-minded individuals without intermediaries in ways that were unimaginable until quite recently.

The very idea of top and bottom feels partial in this context. In addition to the hierarchies of vertical power(top-down, bottom-up) there are heterarchies of lateral power; networks of varying size, shape and influence that often lie dormant but can suddenly be hugely influential in response to particular events, and cut across regions and countries. Such shifts have altered the very idea of social change as necessarily place-based or even country-based, as indicated by Avaaz among others.

4. Inside-out (change stemming from innovations in social and spiritual practices, seeking transformative changes to our ends as well as our means)

Key features: the psychological, spiritual and cultural underpinnings of all the other forms of social change; often contemplative or reflective in spirit, targeted mostly at major hidden assumptions, immunity to change, and adaptive challenges.

As argued here previously, what interests me most is the relatively neglected fourth form of social change about the connection between the work we do on ourselves and the work we do in the world. To grow in confidence and individual agency, to believe we can turn our ideas into reality in a meaningful and not merely tokenistic way, we need to work hard on the consonance between what we think, say and do regularly. And we need a much more robust idea of what to aim for in life, for ourselves and society. Only from that kind of enriched foundation, which we often need to work on ourselves to attain, can we act with conviction in the world.

The inertia within established forms of economic and political power is strong, so we have to keep on reminding ourselves what really matters to us in order to steer ourselves away from financial, social, political and ecological collapse.

And to where exactly? With finite personal time on a physically finite planet, our collective task is to help each other build a sense of power and purpose and use that power to create the conditions that will allow us all to live fulfilling lives. That’s easier said than done with eight billion people,

**

The Cultural Theory of Risk

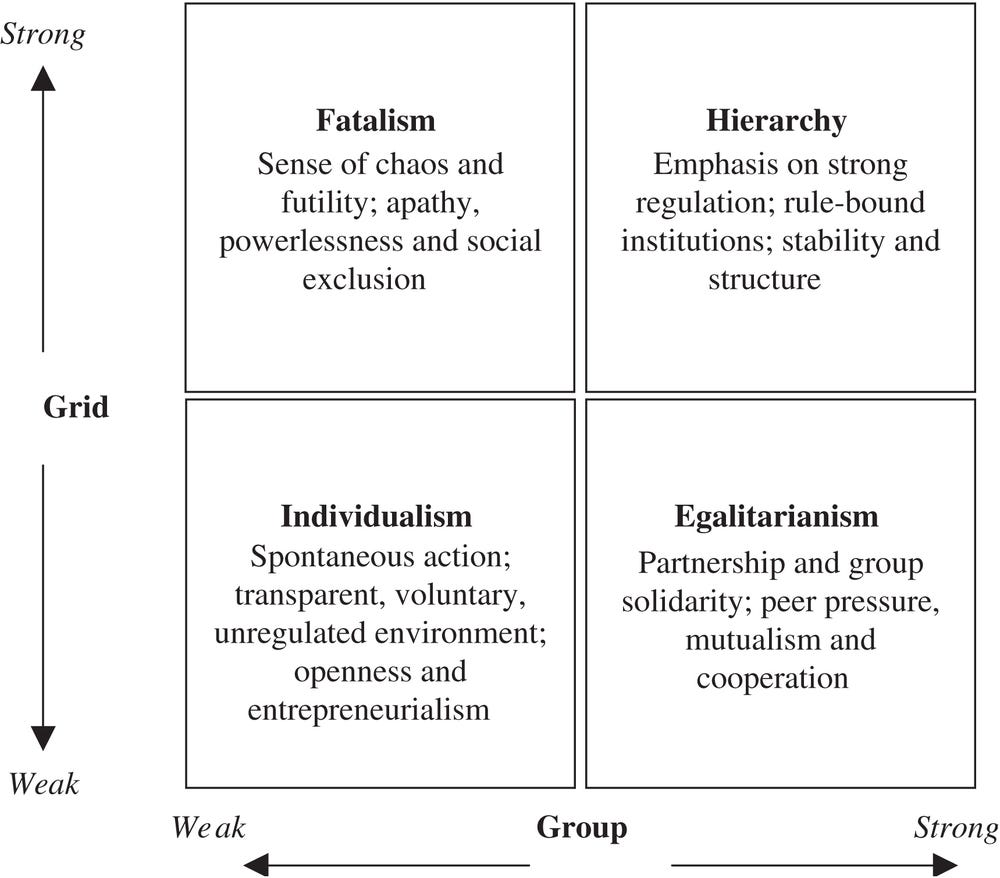

Cultural theory, coordination theory, or theories of plural rationalities is a model to make sense of societal change, including attitudes to nature and attitudes to risk, outlined by Mary Douglas and developed by a range of academics including Michael Thompson, Marco Verwej and policy thought leaders including the RSA’s Chief Executive Matthew Taylor. It is premised on variations in group identification and role differentiation within groups, giving rise to four main models of social change; Hierarchical planners are mostly top-down policymakers, Egalitarians are mostly movement builders, Individualists are mostly entrepreneurs and Fatalists are most nihilistic, but each group acts as an implicit critique of the others.

Barry Schwartz puts it like this:

“Each way of life undermines itself. Individualism would mean chaos without hierarchical authority to endorse contracts and repel enemies. To get work done and settle disputes the egalitarian order needs hierarchy, too. Hierarchies, in turn, would be stagnant without the creative energy of individualism, uncohesive without the binding force of equality, unstable without the passivity and acquiescence of fatalism. Dominant and subordinate ways of life thus exist in alliance yet this relationship is fragile, constantly shifting, constantly generating a societal environment conducive to change.”2

While this theory has considerable explanatory power, what has been overlooked is that the self-proclaimed value of this ‘Clumsy’ approach of mixing methods is post-ideological in spirit and difficult to achieve in our relatively partisan and tribal political atmospheres; it is a higher-order cognitive and emotional achievement of the kind that needs a certain amount of mental complexity to appreciate.

That’s why in addition to top-down (hierarchical), bottom-up (egalitarian), and side-to-side (individualist) approaches there is a need for inside-out work to contend with fatalism, but also to overcome immunity to change. In more advanced versions of cultural theory, there is also a ‘hermit’ who can see the need for clumsy solutions, and I hope to return to that another day…

I first encountered this idea from my former boss at the RSA, Matthew Taylor, and I deepened my understanding through a book edited by Marco Verweij and Michael Thomson (There is a good summary of the idea and its implications for leadership here, and some readers may note potential overlaps with the Cynefin framework but that’s for another time).

I need to chase this source, but I think it’s in the book, Clumsy Solutions for a Complex World

There is also the up-hierarchy which produces "natural hierarchies" as in nature.

See my

https://medium.com/agile-sensemaking/sensemaking-up-hierarchies-a4eea852c139