Reflexive Realism on Climate Change

The deeper rationale behind a new short film starring Olivia Colman

This is an extra post to draw attention to a video that has just been released by Make My Money Matter starring the Academy Award Winning Actress Olivia Colman. It is just over a minute long, a short and striking performance.

Please watch before reading on.

This connection between pensions and climate change is not self-evident to most people. I remember when I first heard about it, around 2012, and it blew my mind.

It’s not complicated, but it does require a different way of thinking because in culture at large, we have too often mistakenly conflated the climate crisis with broader environmental concerns. Noticing this conflation, and waking up to the role finance plays was part of a more general waking up to the full wickedness of the climate crisis detailed in Dancing with a Permanent Emergency.

The basic rationale is something like this:

Pension funds are a major source of savings.

Pensions rely on an investment-return model to work (as part of a broader commitment to economic growth).

Fossil fuels are still considered a reliable investment offering ‘good’ returns.

Fossil fuels are the primary cause of climate collapse (coal, gas, and oil are different, and not equally bad, but can be lumped together as a starting point).

If you are putting money into a pension, and you haven’t asked how your pension is being invested, there is a good chance you are unwittingly supporting the fossil fuel industry.

For this reason, pensions have been called “a black hole of economic democracy’. People think of them in terms of prospective standard of living in retirement but not in terms of collective agency in the context of climate collapse (or, as Alastair McIntosh reminded me this morning, also the arms industry).

There is a case for moving your pension to a provider that does not invest in fossil fuels.

I wrote a report about this back in 2015, called Money Talks: Divest Invest and the Battle for Climate Realism. Not to blow my own trumpet, but as policy reports go, it’s not too shabby. I’m proud of it.

You are welcome to read the report, and the fact that it’s eight years old doesn’t seem to matter too much - the same arguments are still ongoing. However, Bill McKibben recently gave an updated case for divestment in The New Yorker($) in 2021 and I’m sure there are other sources.

*

Here’s why I came to think divestment matters. Waking up to climate change and waking up to its relative importance in the context of other life priorities are very different things. In this respect, we haven’t really woken up at all. As the African saying puts it, “it’s hard to wake a person who is pretending to sleep.”

In this context of relative inertia, with some climate action but not nearly enough, how might we remain authentically positive? Gramsci’s overused distinction is a useful near miss at this point; he said we need pessimism of the intellect but optimism of the will, but on climate change I we need something altogether different: to get real, by shaping reality - what I call Reflexive Realism.

*

Billionaire Philanthropist George Soros attributes his wealth to his grasp of reflexivity – an apparently theoretical notion with huge practical relevance whenever thinking participants are involved. The basic cognitive function of thinking is to understand the world in which we live but the participating function seeks to change the situation to our advantage. When the direction of causation is from world to mind, reality is supposed to determine the participants’ views; but when the direction of causation is from the mind to the world, the intentions of the participants have an effect on the world.

This awareness of the directions of causation from world to mind and mind to world is the sweet spot of climate realism - it’s the premise for ‘getting real’.

‘World to mind’ is what you get when you read projections by the International Energy Agency about continued demand for coal or oil, or read the IPCC forecasts; they evoke optimism and pessimism. ‘Mind to World’ is where the higher quality of realism lies, because there is scope to act in ways that change the conditions of action at scale, whether that’s the presumed climate indifference of your political representative or the plummeting price of solar energy.

For example, it is estimated that every time the volume of solar power doubles, the costs reduce by about 20 percent, a phenomenon known as ‘Swanson’s law’. These connections become clearer when you realise climate change is a challenge across dimensions – science, technology, law, money, democracy, culture, behaviour – and that acting in one dimension has a direct bearing on the reality of several others.

Being authentically positive about climate change therefore means being tenaciously and proactively ‘realistic’ by acting in ways that contravene conventional accounts of reality. John Ashton captures this spirit in his extraordinary open letter to Bob Van Beurden, The CEO of Shell:

“You and those who agree with you have a monopoly on realism and practicality. You are ‘balanced’ and ‘informed’. Your enemies are ‘naive’ and ‘short-sighted’. And you accuse them of wanting ‘a sudden death of fossil fuels’. No phrase in your speech is more revealing. Nobody is asking for this and if they were they would be wasting their time. But the Freudian intensity of your complaint flashes from the text like a bolt of lightning… You seem to want us to believe that the issue is not how to deal with climate change but how to do so without touching your business model.”

Money is the touchstone of capitalism, and one of the best ways to shape climate reality. It’s true that the situation seems objectively grim, bleak and sometimes even hopeless, but as an antidote to debilitating despair, and to open up future possibilities, redirecting money from fossil fuels towards renewable energy is a powerful place to start.

Divest Invest has grown out of this understanding and the movement is perhaps the most successful social and environmental movement ever, with several trillion already withdrawn from fossil fuels because of it. The movement is often misunderstood as tactical protest, a form of gesture politics, but I believe is deeply strategic when it’s properly understood.

The climate conundrum has many dimensions, and I believe it is a spiritual issue at heart, but that doesn’t excuse us from not paying attention to what we can do now. It is also true that climate change is about much more than an energy transition, but again, money is future-shaping. I don’t see the case for divestment as inherently ecomodernist, and nor is it merely a technical solution to an adaptive challenge. What divestment is about is the need to “put our money where our mouth is” as an act of systemic and paradigmatic communication above all.

Now you may well say: “But I don’t have any money” or “Pensions are a privilege”. That’s an important refrain, but we are all one or two degrees of influence away from a pension fund, whether in our family, the organisation we work for, or our local council, so it’s not true that this case only applies to the rich.

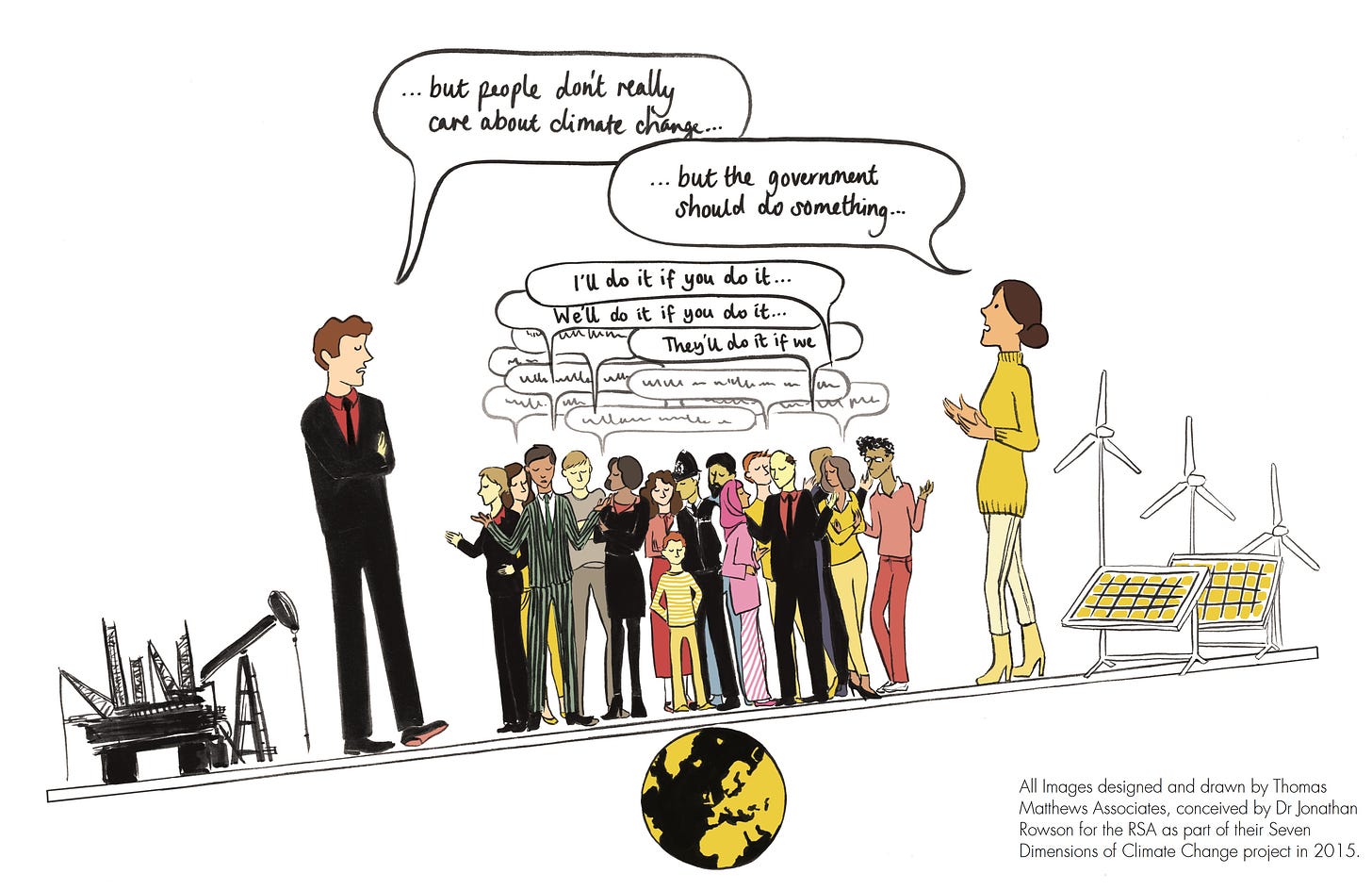

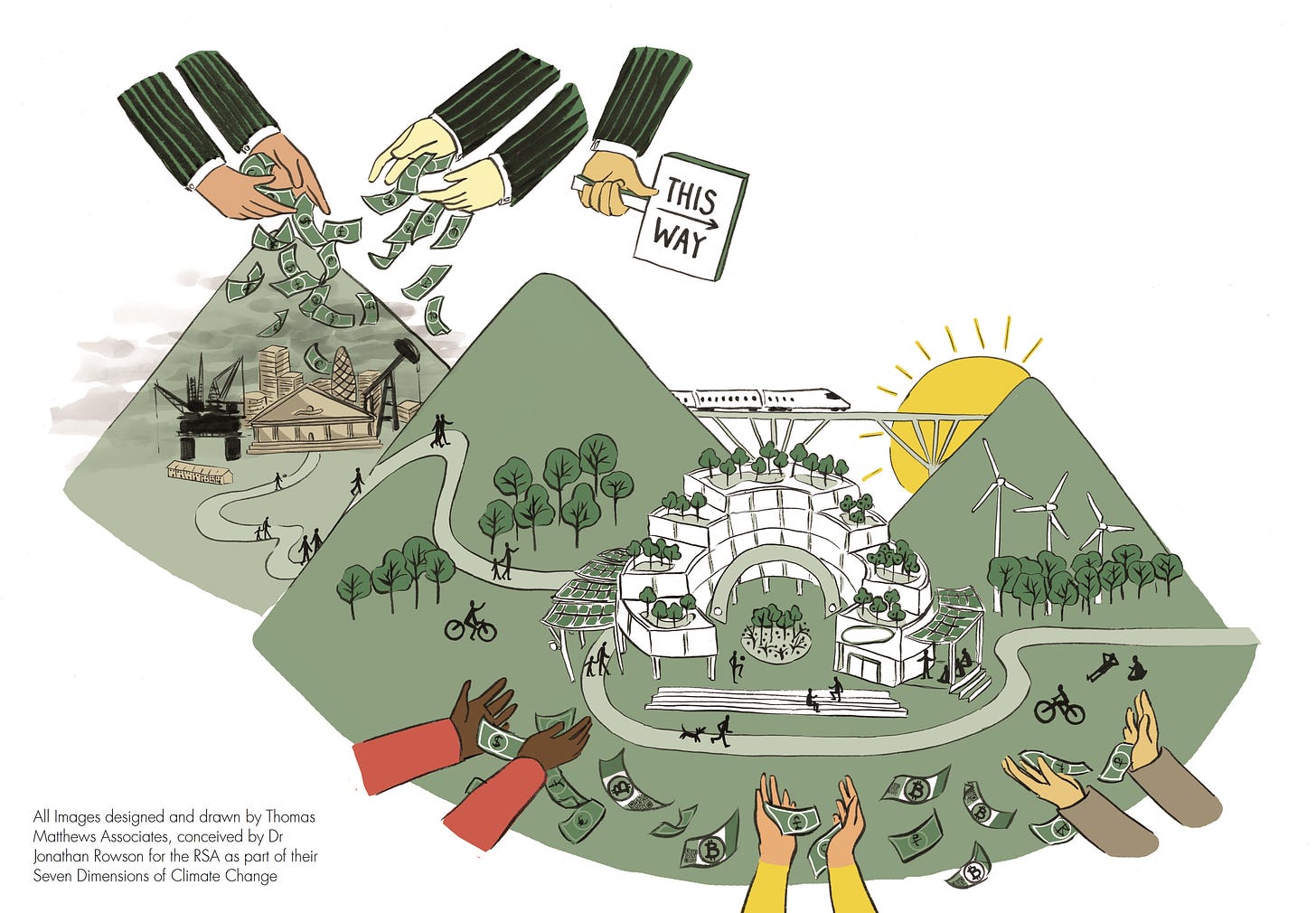

The following images speak to how divestment works strategically better than words. They arose from The Seven Dimensions of Climate Change project I ran at the RSA.

The democratic trap is that there is a climate majority, but it is not politically mobilised. I am glad friends like Rupert Read and Liam Kavanagh are doing something about that with their Climate Majority Project.

There is a legal case for preventing fossil fuel prospecting, for ‘keeping it in the ground’, and were this to happen it would have significant knock-on financial implications. There is a great deal of climate litigation under way, including at FORGE at NYU where I was earlier this month.

And there’s a simple economic case that by investing we send a signal that leads to further investment, and in so-doing there are even potential financial returns on offer for those who get ahead of the game (but I think it’s a mistake to make that the reason for doing it).

It’s roughly like this: At a democratic level, divestment challenges the political power of the fossil fuel industry as it manifests in subsidies. At a cultural level divestment stigmatizes the continued investment in fossil fuels, attempting to remove their social license to operate. At a technological and monetary level, it signals to financiers that we are at the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era, encouraging them to redirect their money towards new forms of research and infrastructure. At a behavioural level, divestment wakes people up to their unwitting financial complicity in the challenge, and gives them a way of acting that feels commensurate with the global and systemic nature of the problem.

And even if you doubt the strategy, there is a simple matter of logic. There are estimates, assumptions, and qualifications at every stage, but the case for divesting from fossil fuels and reinvesting in alternative energy flows from premises to conclusion as a form of deductive reasoning in roughly 10 parts. Full references are given in my RSA report: Money Talks: Invest Divest and the battle for climate realism. (Pages 29–31) and some of them will be dated now, but it goes roughly like this:

1. There is a scientific consensus on anthropogenic global warming, showing a clear relationship between rising carbon dioxide emissions and atmospheric warming.

2. There is an agreed constraint on temperature warming (2°C above pre–industrial levels on average) widely considered to be the upper limit of acceptable risk for maintaining the quality and viability of our habitat.

3. To stay within that limit, there’s a commensurate total global carbon budget we can’t exceed, and we have already used more than two–thirds of it.

4. The IPCC estimates (*or did back in 2015) that to have a chance of staying within the temperature limit, global carbon dioxide emissions have to peak by roughly 2032 and fall rapidly towards zero before the end of the century.

5. Most carbon dioxide emissions stem from fossil fuel combustion; estimates range from about 78–87 percent of the total.

6. To stay within the remaining budget there have to be stringent constraints on fossil fuel extraction, or sufficiently developed carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology.

7. However, CCS has stunted potential primarily because it lacks efficacy in reducing net emissions (the process uses significant energy, it does not capture all carbon dioxide emissions, and there is a small residual risk of leakage). Compared to other low–carbon power sources it is costly and slow to deploy at any scale. While CCS is factored into many climate projections, it is reasonable to discount any significant contribution that will be made by CCS within the time constraints implicit in the carbon budget.

8. It follows that most existing fossil fuel reserves are overvalued because they cannot be used without contradicting the scientific and political consensus. The best current estimate (*as of 2015!) suggests that from known reserves, to remain within the 2°C limit, we will have to leave 88 percent of available coal, 42 percent of available gas, and 33 percent of available oil in the ground.

9. Given global energy demand is likely to rise rather than fall, it also follows that to maintain a functioning economy and society we will need a swift energy transition to decarbonise the world’s economy, which means rapidly developing alternative forms of energy infrastructure with speed and at scale to gradually replace rather than merely supplement fossil fuels.

10. Fossil fuels will remain a necessary part of the world’s energy for some time to come, but we are compelled to make that time period as short as possible. For moral and financial reasons, we therefore need to stop investing in fossil fuels and invest instead in alternative energy.

We can remain authentically positive on climate change by strengthening and accelerating the decarbonisation process. There are of course huge psychological, cultural, moral, and democratic factors in play, but Divest Invest is built on the relatively solid premise that finance drives technological change and technological change shapes society.

Without 18th century coal there would have been no 21st century solar and wind. From an engineering perspective, we have what it takes to transform. What remains unclear is whether we can bend the arc of reality fast enough.