When my exquisitely grumpy compatriot and world class tennis player Andy Murray retired he said something resonant:

I think I’ve persevered. And that, really, has been the story of my career.1

I’ve been thinking of this line recently in the context of the state of the world, my place in it, and what it means for any of us to keep going.

Now you might ask: why should we keep going? Isn’t it better sometimes just to stop?

And is it not absurd to advise people to keep going, when most of us don’t know where exactly we are going or why?

The world will do its utmost to stop you from persisting, and yielding to the world is not always a mistake. As I’ve said before, the best move I made in my chess career was knowing when to stop. Many have misspent their lives chasing the wrong dream. More to the point, some of the happiest people have no particular sense of direction becuase they are already there, and feel they have what they need.

There is a story of a man who finds himself in what appears to be the middle of nowhere. He sees a woman who looks like she lives locally and asks her how to get to, say, London. She says: “Sorry I don’t know.” He says, “Ok, well perhaps you can you tell me then where the nearest town is?” She says: “Sorry, I can’t direct you from here”. He says": “Ok then, can you at least tell me how to get back to the main road?” She says: “Sorry, I don’t drive and I am not sure.” The man, slightly exasperated, says: “Well it seems you don’t know much at all, do you?”

“Maybe”, she says, “but I’m not lost”.

The sense of ‘keep going’ I am after is more like the title of a Mark Epstein book called Going on Being. The injunction to keep going doesn’t insist on direction, nor does it preclude rest or reorientation, and it might well entail questioning your assumptions and priorities. I highlight the challenge of how to keep going mostly as an antidote to lethargy and despair in the context of a demoralising news cycle and ambient relational and administrative pressure. I am interested in what it takes not so much to get up in the morning - becuase a reliable alarm clock and a strong coffee can do that. The deeper challenge is get yourself to bed with an appetite for sleep that is stronger than the miasmic screen that is keeping you awake, because you know that something real matters tomorrow and you want to be there for it.

I am also reminded that during the pandemic when nobody knew what was going on or how long it would last, I was comforted by The Keep Going Song by the Bengsons. While it is definitely Covid-specific it is also one for the ages. (*Warning: this song poses a significant danger of earworm; though some believe it is a healthy variant*)

*

So what does it mean at the moment to keep going?

David Whyte is often quoted as saying that the antidote to exhaustion is not rest, but a return to wholeheartedness. The original source however is Brother David Steindl Rast. His re-articulation of this point relates to prior posts here about the significance of the heart as an organ of perception.

…When you’re not committed, so much energy leaks into the question, should I or should I not? And it’s wasted energy. But if you’re committed, all the energy goes in that direction……I think David Whyte asked me once about exhaustion and burnout and so forth. All you need to do is do the same thing that you are doing now but wholeheartedly. And this wholeheartedness is with all that energy that comes up from that deep well within us. The heart is, so to say, the taproot of all our being, where intellect and will and emotions and body and mind and all is all one. That is what we call the heart. Put all of that into what you’re doing. I think that is a good recipe against burnout.

All you need to do is do the same thing that you are doing now but wholeheartedly.

That’s quite a line, and I think the idea is that we can’t do aimless pointless things wholeheartedly, so they will drop away naturally as we figure out and enact what we are committed to. This way of framing the human challenge to keep going is worth juxtaposing with one of Samuel Beckett’s signature lines:

I must go on, I can't go on, I'll go on.

You can’t go on because it’s all too much. But maybe you can go on, even if that means wholeheartedly deciding to stop doing anything you are not committed to. Commitment and focus are exacting challenges when we live in a distracting world with a mind that fears missing out and is built to detect change and novelty; and it’s getting harder in an attention economy that is distractionogenic by design. I also think diversion, distraction and deviance are valuable features of the human experience; I wouldn’t want to live entirely without them. But nor do I want to be at the mercy of stimulus that is not of my choosing. Living with an underlying vector of wholehearted commitment is possible, and worth striving for.

**

I feel personal, political, and professional dimensions to the challenge of keeping going, and I linger here mostly on the last of these.

At a personal level, keeping going feels like a kind of duty.

My closest family needs me to keep going, and mostly I do. I’m lucky that when I feel I can’t keep going; when I can’t answer another gratuitous question, surrender to relentless admin, make another family meal or wholeheartedely do the dishes for the third time that day, there is usually flexibility, forgiveness or backup that allows me to rest, so that I can, you know, keep going. This aspect of life corresponds to Hannah Arendt’s Labour, which is about the life-sustaining activity of daily life of a mostly cyclical and biological nature, contrasted with Work - the production of durable objects, and Action - the creation of meaning in the public domain. Arendt’s views are invariably enlivening and elucidating, but the conceptual coherence of this trio of Labour, Work and Action, first articulated in The Human Condition from 1958 needs remedial attention in the age of the smartphones, digitalisation, working from home and many other things that blur the distinction between these three forms of activity.

The labour that is the duty to keep going is also a kind of dharma which I feel from the influence of Hinduism on my life through my wife Siva. There is no direct translation from the Sanskrit but dharma adds to duty a notion of virtue or even of cosmic path. To keep going for the people around you. To do what is clearly yours to do. To be who you have to be on a daily, repeated basis. I struggle sometimes, I admit, but we need to find, inhabit and do our duty, trust that our loved ones will help us, and that we are worthy of their love and their help, and what that makes possible. Freedom is not infinite possibility. Freedom is choosing your constraints and claiming them as your own.

As George Eliot once put it:

The reward of one duty is the power to fulfill another.

*

At a political level, keeping going feels like hope.

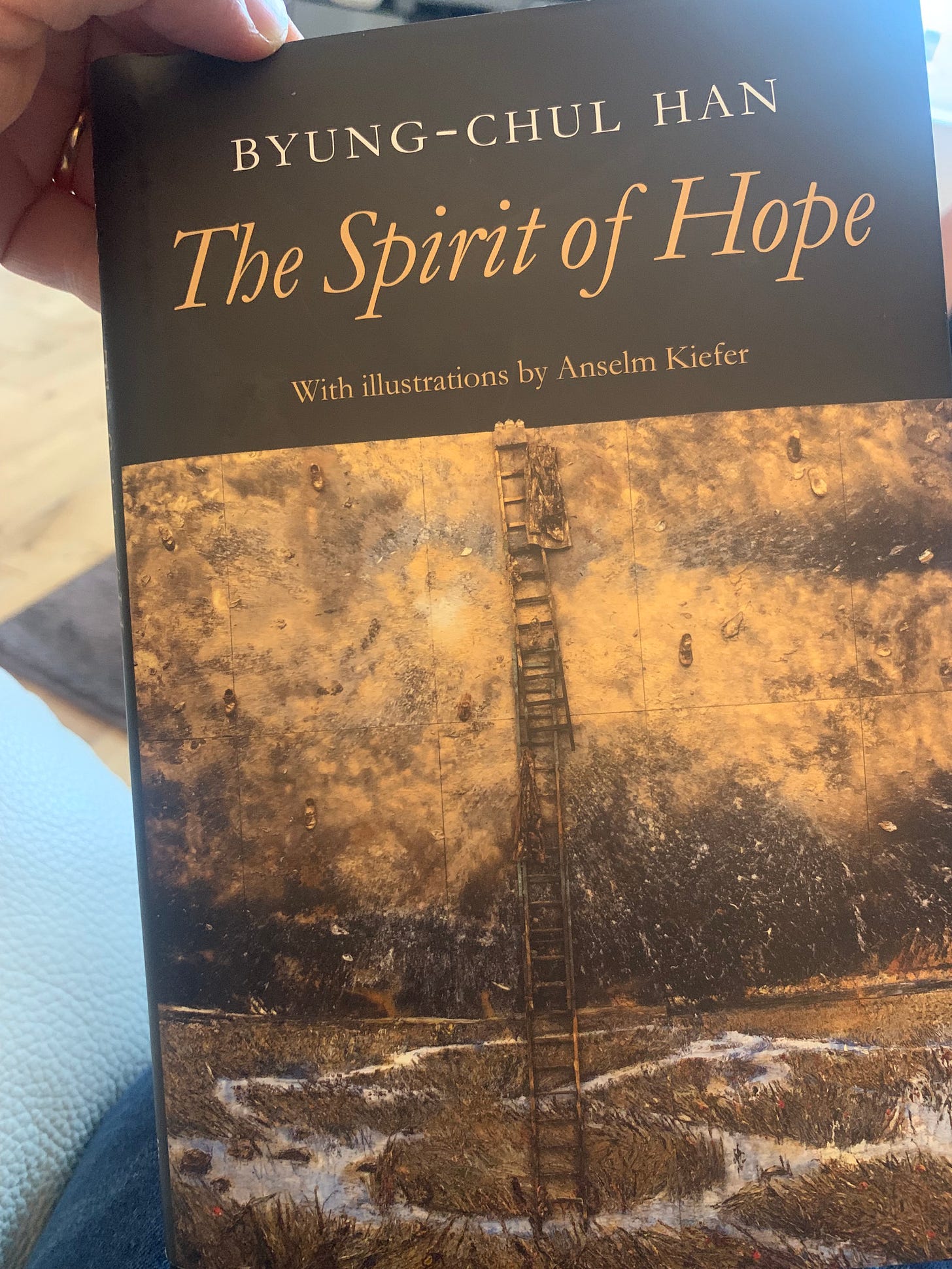

I visited my father over New Year, ‘for the bells’ as we say in Scotland. I stayed for three nights in a rented flat by myself partly because the agglomeration of my dad’s art and art materials had supplanted all the places it might have been possible to sleep, but after a challenging year I also craved some solitude. So I began 2025 by taking a break from human beings and I read The Spirit of Hope by Byung-Chul Han from start to finish.

The book is 86 pages short and so rich with meaning that nothing needs to be highlighted except for the whole thing. The book wrestles hope away from facile wish list optimism and restores its intellectual dignity and spiritual depth. Hope can be active, generative, and transcendent; it is an antidote to fear and anxiety but on Han’s account it actually deepens with despair. The argument is fundamentally about how the open future inhabits the present, and our responsibility, perhaps duty, to perceive and evoke the potential within it. As Han puts it:

“…Hope does not stand upright. Walking upright is not its fundamental posture. It leans forward in order to listen intensely. Unlike the will, it does not rebel. Hope is the beat of a wing that carries us.”

This was a good way to start in the second quarter of the 21st century and I hope it might help to keep me going too. The book is quite abstract, but abstraction is also a kind of distillation, elucidation, and even a kind of play for a certain cast of mind. Han does a good job of acknowledging lots of anti-hope theorists and explaining what he thinks they are missing; I tend to side with him there. Hope is not another word for optimism but almost an antonym. I also feel Han is as clear as anyone could be about what hope is, though it’s multidimensional so the demand for clarity needs tempering too. He quotes Vaclav Havel approvingly as hope being “a dimension of the soul”, “a state of mind”, an “orientation of the spirit” and says that it “shows the way” - he links hope both to knowledge and action but most critically to a conviction that the future is open.

Despair is what arises from looking at the daily news cycle too closely and being subject to what Peter Limberg recently called ‘the pull’ illustrated by the image below where we are hunched over and held captive by a stream of information that is a kind of dehumanising programming and entrapment. (I can’t currently trace the original source).

*

Instead of the pull, hope as leaning forward and listening intensely makes me think of the third horizon in Bill Sharp’s Three Horizon Model, namely possible futures somewhat beyond the conception of our current social imaginary.

My day job running Perspectiva is about this kind of listening to the future and I am part of an emerging field of inquiry and practice that, in Han’s terms, is trying to grow the wing that might beat for us and carry us. (For those who only know me from The Joyous Struggle, you might enjoy getting to know the broader social field my work is part of, which I described in a seven-part series in 2022 called: Now that you have found the others, what are you going to do?).

The challenge is that most people working on visions for the future struggle to get funded in the world as we find it. When the investment and return through growth pattern is the root of the problem, and philanthropy still depends on it and even fuels it, finding a way to finance viable futures is the Enigma Code challenge of our time.

I don’t think the ‘non-proft’ people are going to overpower the ‘for profit’ people with research, mobilisation or moral advocacy, and I don’t think the ‘for-profit’ people know how to get off the destructive treadmill that their success and status depends upon. The stuckness runs deep. The incentive to continue as we are is still greater for the critical mass of people than the incentive to change. Habit energy is formidable. Fear is strong. Destructive power is metastatising. Collective transformation is not easy and not likely, but it is possible.

The combination of dizzying change and endemic inertia is partly why I argue that metaphysical transgression, cultural transformation and political realignment will have to co-arise, and why I see each of the Flip, Formation and Fun as essential points of orientation and motivation today.

And so this is how keep going shows up for me professionally: as commitment.

I am going to focus on just one aspect of this for now - the challenge of paying for work that might act as a countervailing power to the forms of power that appear to be destroying the world. We have to commit to changing this, but I am still unsure how it might happen.

We recently had a house guest who works mostly as a climate journalist. She said she once had a partner troubled by her activism and what it meant for their joint social life to always be hanging out with people agitating to change the world. In fact, he even asked her: “Don’t you have any for-profit friends?”

The non-profit model is particularly hard to sustain because if you succeed - and that’s both hard to define and achieve - you tend to become a victim of your success. It’s worth briefly reflecting on this point which I feel isn’t widely enough understood.

In a commercial enterprise, as you grow you tend to increase your revenue relative to your costs (in economics language, marginal revenue per unit of output goes up, as marginal cost per unit goes down). So in a back-of-the-envelope-kind-of-way, your first coffee in your new cafe may sell for £2.50 but may have cost £250,000 in start-up costs to make the business possible, some of which may have come from investment for equity share. Your second cup will sell for £2.50 too, and there is a long way to go before you make a profit. Yet many of the costs are behind you, and if you make £250 in your first day, word gets around, and £2500 in your first week and £25000 in your first two months and keep growing such that you earn £250,000 in your first year, your second year looks very promising indeed. Of course, your coffee might be bad, you may have opened in a low foot-fall area with a questionable lime green aesthetic and muzak; so you may make merely £25 on your first day, £500 in your first month, £25,000 in your first year, fail to get further investment, wake up and not really want to smell the coffee, close the business, and suffer a mental breakdown.

In a non-profit enterprise, the path to mental breakdown is a little different. You want to oversee, say, a research-led advocacy project on prospects for improving the sustainability and ethics of the coffee industry including models of cooperative ownership and their implications for bioregional governance and you’re excited about all that this means; but you need £250,000 to cover the salaries of a small team of five people and other running costs. You do great work together and produce a field-changing report on time and budget alongside an event covered by the figurative nine o’clock news that is mentioned by your local MP in PMQs in Parliament (and you managed this despite being human; one member of staff needing extended compassionate leave, another two struggling to work together, and losing a month in a failed funding application and intra-team dynamics).

So now what? Your research indicated that you need a much wider boundary of inquiry to properly understand what’s going on, and you feel you are ready for that more ambitious inquiry. You’ve also met some great people through the process that you would love to employ, but you have no revenue stream. Your main funder is still eager to help, but the capital markets were not kind to their endowment last year and they are inundated by requests from those tea researchers who should be your allies but sometimes feel like rivals, and they say that they can only offer you £150,000 this year. So you forgo the raise you think is warranted and lay off two valued staff members who feel they have no choice but to become co-founders of a cafe chain that may not last a year.

Meanwhile, you spend two months trying to raise additional funds for your more ambitious project that you think will cost £300,000 in total, but nobody seems to understand it, you can’t find or afford a suitable designer to give it the deft visual oomph it needs. So you accept you have to proceed with something more modest this year, but then your main contact at the foundation changes jobs, and your new contact does not connect with you in the same way, and they seem a bit disappointed by the apparent lack of progress since the great start, and they won’t return your calls. So you wonder how you’ll keep the show on the road.

There is another scenario in which you succeed in raising the £300,000 (though it takes several months of work) and keep growing, but that means your costs keep rising. Unless everyone who joins the team is fabulously entrepreneurial or you are funded by a private individual with deep pockets and long arms, sooner or later you will need to create a different revenue model. That shift means asking for fees, charging for your outputs, and very often means compromising on doing the work your expertise tells you is most necessary and your team is best placed to do, and you would do if you were not financially constrained.

Perhaps I exaggerate. I shared that confected coffee drama to convey that merely surviving and staying on task is a challenge. If you are doing meaningful work, just to keep it going and not collapse into merely serving Capital can feel like a heroic achievement. You may rightly perceive that to keep going is not enough for the world’s needs now, but if you believe in your work I hope you are surrounded by people who encourage your commitment and tenacity. It is your duty to go on, maybe, and it confers hope.

So keep going.

*

I’ll end with a 15-second clip from The Two Towers, the second movie in The Lord of the Rings trilogy, which I recently watched again with my younger son Vishnu. Just before this moment, the dwarf Gimli is clearly struggling to keep the pace, feels completely unsuited to the terrain, and amusingly says: “I’m wasted on cross country, we dwarves are natural sprinters…”. Gimli is a tragicomic figure in the films more generally; tragic because he may be the last of his kind, and comic because his character is frequently at the centre of moments of levity in an otherwise serious story about the fate of the world. I’m sharing this moment here because we all have some Gimli in us, and because to keep going we need to follow his advice:

Keep breathing. That’s the key. Breathe.

With a nod, a wave, and some fond memories, I’ll leave commentary on Tennis sporting careers to others, but persevere is an interesting word. The English word ‘severe’ is hiding there, but the term is not generally so harsh and relates to steadfastness and enduring persistence.

While Google n-grams are NOT reliable and should not be confused with science, at a purely indicative measure from the search of books available to Google, it looks like we have not persevered with the word perseverance.

You can’t infer anything from something that means nothing, but I’m still curious about why the word went out of fashion. ‘Persist’, for instance, apparently made a comeback around the time electric lighting entered commercial production and the two-blade electric fan was invented.

Persistence overcomes resistance, they say. Some years later, “Nevertheless, she persisted” became a morale-boosting motto for aspects of the feminist movement…

C.f. Dory's 'Just keep swimming'

Good piece! keep on writing!