In my opening post on The Future of Peace I wrote of my growing realization that peace is not merely preferable but also more interesting, challenging, and imaginative than war. I shared a few existing rigorous ways of understanding peace and suggested - though I would be happy to be shown otherwise - that we may not (yet) have an idea of peace or a praxis of peace that is worthy of 21st-century challenges. Our challenge today is not just that nations are at war, but also that the world appears to be at war with itself, by which I mean at war with nature, with reality, with vanishing islands, with other species, and with the past, the present, and the future. In my second post, I wrote about Gaza, and this post was supposed to be the last one, about Ukraine, Climate Collapse, Democracy, and AI. But then to my surprise, the muse wanted to write about Star Wars, which means I have to postpone those thoughts until the fourth and hopefully final post on peace.

As indicated, I believe peace is the defining intellectual and spiritual challenge of our times. To put it simply, we have three main possible futures (or ‘attractors’ in the complexity basin sense of drawing us towards them), and two of those three futures lead inexorably to a version of World War Three. This is just a model, not a prediction, but when you look at the co-arising of threats to global security over the next decade or two, the most plausible (to me) scenarios appear to lead to ecological, social, economic, and political collapse and the wrong kind of anarchy, and/or dystopia in the form of tyranny, for instance through authoritarian governments using AI to control populations through mass surveillance.

There is, however, a ‘third attractor’, at least in principle, and people are beginning to articulate it. Somehow, perhaps propelled by ‘the flip’ in perspective about who we are, we navigate technology well and evolve through a spiritual, cultural, and intellectual renaissance into some kind of (and here I’m freewheeling a bit…) wisely governed, polycentric, pluriversal, regenerative, cosmo-local, bioregional, open society that is continually learning, creating and caring, not merely as means to other ends, but as our preeminent societal ends. Maybe. Such a world will also need some resistance, some struggle, and some conflict to remain resilient and healthy.

See you there?

So much, so fanciful and speculative. What is clear however is that in light of our technological power and ecological precarity, peace is a necessary condition for a wisely governed world to even have a chance.

Peace is the sine qua non of any third attractor.

And if you don’t know what sine qua non means, I didn’t either until I was 26. While considering where to do a Ph.D., and with half an eye on my chess career, I asked an anthropologist at the University of Edinburgh if I could do their three-year doctorate without doing a year of fieldwork overseas. He said: “No. Fieldwork is the sine qua non of Anthropology.” I didn’t proceed but came to love the term, which is literally ‘without which not’ in Latin, and means the thing that makes the thing the thing it is.

So far, so abstract. What does this mean in practice?

First, if you’ll indulge me, let’s consider what it means in outer space (which is after all where we are) where there is a weapon that is almost the antithesis of peace, and to consider it we need to begin:

I have lost count of the Star Wars films, and I’m not sure which I enjoyed the most, but I did like The Last Jedi. That final scene with a disgruntled but ultimately redeemed Luke Skywalker tele-transporting an apparition of himself to buy time to save the others before literally disappearing is the quintessence of the Eriksonian choice of integrity over despair in our latter years. (I also love the intensity of the chemistry between Kylo Ren and Rey).

However, Rogue One is a peace allegory that I want to explore here.

The film was released in 2016 but sits in a narrative chronology just before the original Star Wars in 1977 (when, along with 3,326,631 other people, I was born).

At a time when The Empire (fascists) are in charge, the plot of the movie is about the gradual formation of a rebel alliance (open society enthusiasts) that, against the odds, succeeds in preventing The Empire from using its diabolical planet-destroying weapon, The Death Star, to annihilate whole planets from a safe distance.

There are some subtleties. The Death Star has only recently become operational. The main architect of the hyper weapon (which is a space station and looks a bit like a planet) is a rebel scientist captured and coerced into completing it several years before, and he deliberately created a weakness in the design; a detail that can only be found if you know to look for it (and where) in the well-secured and protected infographic plans hidden on the planet Scarif, which have to be retrieved.

Learning of that subtle act of rebellion gives a glimmer of hope to the rebels but the challenge is keeping morale intact, building a movement, and then finding the plans, getting back to the Death Star, and finding and exploiting the vulnerability in a way that disables the weapon before it can destroy (more) planets; all of which requires abundant skill, guile, luck, and the Hollywood bias towards happy endings.

The setting of Rogue One is ambient despair and the plot is resistance. The point is that to win any given battle your first job is often just to prevent defeat. The heroism in play is that of the goalkeeper who saves the penalty, not the striker who scores the goal. And so when Rogue One ended, initially it felt to me like something was missing.

Is that it? All those characters and their struggles add up to disarming a weapon? Where’s the epic lightsaber battle, the thrilling twist of fate, the post-tragic “I’m your father, Luke” verkempt crescendo? Instead, disarming The Death Star felt temporary and anticlimactic because the baddies were still at large, and the weapon could and probably would be rebuilt.

But then, suddenly, I ‘got it’ at an emotional and philosophical level (for me they’re often the same). The heroic efforts on a galactic scale are for the love of continuing to exist, for the sake of preserving life as possibility. Director Gareth Edwards said of Rogue One: "It comes down to a group of individuals who don't have magical powers that have to somehow bring hope to the galaxy."

As one of the characters, Jyn Erso, puts it about the improbable odds of retrieving the plans (only one part of the overall scheme).

"They've no idea we're coming. They've no reason to expect us. If we can make it to the ground, we'll take the next chance, and the next, on and on until we win, or the chances are spent.”

If that sounds like low-brow hyperbole, the statement reminded me of a line attributed to the Italian mystic, poet, and friar St.Francis of Assisi (c. 1181 – 1226):

“If at first you do what is necessary, and then do what is possible, soon you find you are achieving the impossible.”

I’ve used that line in talks I’ve given about the challenge of climate collapse, and it applies just as well to peace. The necessary/possible/impossible framing also corresponds roughly to triage/transition/transformation in the three-horizon model detailed in a previous post about The Inner Life of the Future here.

First, do what is necessary.

Then do what is possible.

Hope for peace lies in seeking out ‘The Death Star’ and disarming or destroying it.

*

But what is the modern-day equivalent of a weapon of absolute destruction?

The obvious answer is nuclear weapons, but that misses the point. You don’t have to believe in mutually assured destruction (MAD) theory being a deterrent to see that a situation where at least seven countries: USA, Russia, China, UK, France, India, and Pakistan, have such weapons; and at least three others: Israel, North Korea, and South Africa may have them, is different from the Star Wars asymmetric binary where only one side seeks to destroy. We are not in the middle of a Cuban Missile Crisis, and it’s easy to forget that nukes are still there, waiting to be used; but it’s important to remember that the situation could rapidly change. As Bertrand Russell once put it:

“You may reasonably expect a man to walk a tightrope safely for ten minutes; it would be unreasonable to do so without accident for two hundred years.”

Since The Death Star is merely the physical manifestation of an underlying idea, there are many ways to think of how it manifests more or less latently today.

Last week, in The Future of Peace 2/3, I began with the current situation in Gaza, where in my view the prospects for a lasting peace are, sadly, now vanishingly small. As things stand, it is very hard to see anything resembling the social, economic, cultural, and political conditions for ‘structural peace’, and that’s because, in Gaza at least, things don’t stand. They have mostly been destroyed. In that particular situation, it seems to me that the Death Star is the misplaced demand for absolute security from terrorists manifesting as indiscriminate violence against civilians.

The situation is only slightly better in Ukraine. There the Death Star is old-fashioned imperialism, the blood lust for territorial expansion. On ecological collapse, the Death Star is delusion and denial, on AI the Death Star is lack of regulation and on Democracy the Death Star is disinformation. We’ll come to all those in the next post.

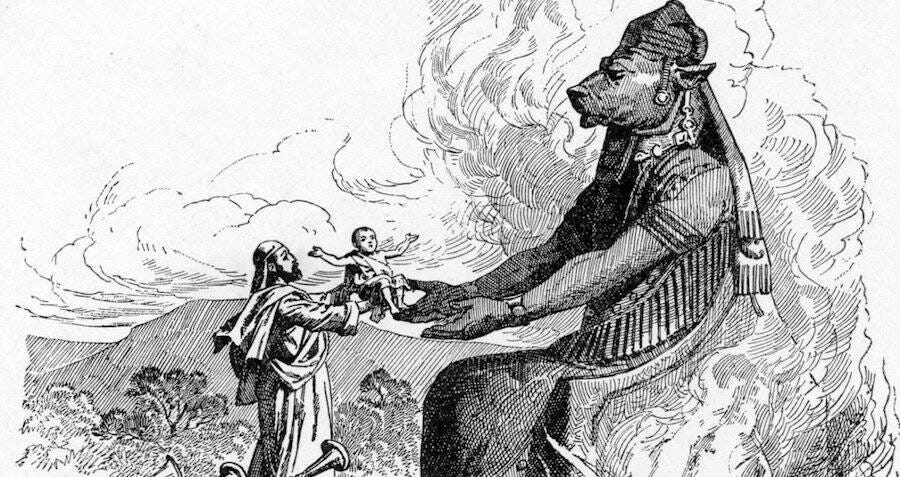

The more discerning modern match for the Death Star is Moloch. In Moloch in Therapy I describe how game theory sets up Moloch as “The God of coordination failure, or the spirit of unintended consequences, the secret reason that good things turn bad. Moloch…is usually depicted as inorganic, as some kind of statue or machine…the thing that is not of true value toward which people nonetheless feel obliged to sacrifice things that are of real value.” If peace today means recognizing that we are at war with ourselves, Moloch represents our inability to respond to ecological collapse or technological developments with sufficient resolve due to the inertia caused by competing commitments.

It’s difficult to pin down Moloch ontologically, and perhaps unwise to try because Moloch is, in Bayo Akomolafe’s terms, onto-fugitive, somehow always fleeing capture by categories. Moloch is the symbol of negative outcomes caused by inexorable competitive logic arising from a lack of imagination and unwitting design. Moloch is a complex suprapersonal notion, but you can think of it as our underlying socio-economic logic, which is why I see a parallel between slaying Moloch and the need to retrieve the infographic to disarm/destroy The Death Star.

The future of peace depends upon vigilance about Death Stars. Our challenge is not just to prevent material death stars by slowing the (further) development and spread of weapons of mass destruction, but also to consider spiritual death stars, and protect peace from being destroyed indirectly by socioeconomic, political, and cultural means. What is necessary is not just to destroy violent weapons but to transcend harmful ideas.

(That was a strange post, but somehow it had to be written. See you next time!)

"But then, suddenly, I ‘got it’ at an emotional and philosophical level (for me they’re often the same)."

Important line here.

What I never see addressed, is the huge and essential difference between analysis, after the fact, like you do with the Star Wars plots, and modelling or prediction. While there is good reason to apply experience to expectations, these indicators can never lead the way. So the question becomes what can, should be in charge moving forward.

The guy from Assisi is telling us, and I recognise a person with good hands there. Who knows how to accomplish stuff in the physical world. Ask the master builder, not the strategist, and he will tell you the soul is in charge, not the plan, not the possible, not the imagined outcome, not the will. And this is very similar to what McGilchrist calls the right hemisphere way. It says, among many other things, that we must become weary of all forms of representation. Not do away with them, but prevent them from having the deciding power.

Making a list of all that should not be in charge and outline appears. Never to be named, never to be grasped, never to be set in stone. But kept holy. It is the unwritten.

The crazy thing with McGilchrist's work is that the insight is nothing new. And the great danger of his analysis is that it now is up for grabs. To be integrated and institutionalised. Like a fourth move in the hemisphere manoeuvre. Peace to me, is not external first. Internal peace is about the relationship of me and my ecology. Me and my home. It radiates outward from my core. Making my peace my responsibility and nothing more.

I don't believe in attractors, I believe in radiators.

Thanks Jonathan. My comments at https://johnstokdijk538.substack.com/p/lets-defeat-moloch.