Therapist: Come in. It’s nice to meet you. There’s a glass of water for you on the table under the lamp there. Do make yourself comfortable.

Moloch: Thanks. Let’s see what I can do. *Figuratively sits down*.

Therapist: So what brings you to therapy?

Moloch: That’s a very personal question.

Therapist: Is it? Well, that’s good. Therapy is personal work.

Moloch: Well, I am not really a person. God made sure of that. On the other hand, I sometimes feel like one, and it’s not clear what I am. Technically I suppose I’m a demon, but these days I am invoked by humans to represent negative outcomes caused by inexorable competitive logic arising from lack of imagination and unwitting design.

Therapist: *Scribbles note: ‘complex identity structure, possible narcissistic personality disorder’ and looks up*.

Can you explain that to me in plain language, please?

Moloch: There was an old lady who swallowed a fly. Remember her? I guess she died, right? And why? Because one thing led to another.

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly, she swallowed the bird to catch the spider that wriggled and jiggled and tiggled inside her, and so on. The old lady soon found she had to eat a horse to solve her problems. As the saying goes: good luck with that.

Therapist: So are you the horse?

Moloch: No! I’m the kind of underlying logic that leads people to figuratively eat horses to solve their fly problems.

Therapist: I see. You are a pattern or an operating logic of some kind, then?

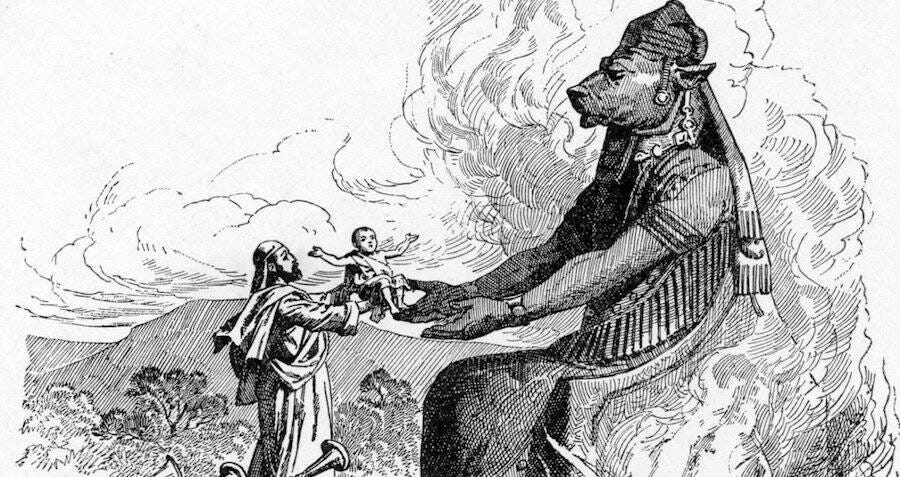

Moloch: Yes, I suppose. Some think of me as a version of the devil, like one of his many flavours from the same tub of diabolic ice cream. More precisely I am the God of coordination failure, or the spirit of unintended consequences, the secret reason that good things turn bad. Moloch in particular is usually depicted as inorganic, as some kind of statue or machine.

I consume things of value, and that’s how I’m appeased. But that means I’ve become the thing that is not of true value toward which people nonetheless feel obliged to sacrifice things that are of real value.

*Looks sad*

I used to be the child sacrifice guy. Yes, ok, I accept that was wrong, but at least it had some symbolic power. These days people don’t give me their babies at all. Instead, they feed me with smartphones and GDP figures and tall buildings like The Shard in London and or The Burj Khalifa in Dubai, and they expect me to be grateful. I’ve become a niche social and political touchstone or metaphor to explain all that.

They say I’m the spirit of things that are jinxed by the logic of how things play out, like capitalism being unable to stop itself from committing ecocide. Some even talk of me these days like I’m the capitalist system itself.

I have become the name for ‘the thing’, ‘the machine’.

Some people even seem to think of me as a kind of dark power that is potentially going to somehow inhabit the infrastructure of artificial intelligence. But no, if anyone’s going to do that it’s my colleague Ahriman. Others see me as self-defeating exponential technology, driving the planet to destruction.

They also say I’m the spirit behind the creation of the nuclear bomb, and the arms race that followed - nobody wanted anybody to have the capacity to destroy the world, but everybody knew that somebody would do it first, and once that awareness arose, others had to follow. That recent movie Oppenheimer has so many head shots of the main character looking with his big translucent eyes at something in the mid-distance with a mixture of awe, regret, guilt, sorrow, hope, confusion, and fear. They don’t say this, but what they are trying to convey is that he’s looking at me.

*Looks at therapist*

Therapist: *Looks back, and smiles.*

I see. It sounds like you have more to add.

Moloch: I was never truly embodied, but I miss being iconic. You know, in some depictions of me there were even hoooves, red eyes, and horns. Not bad. I miss them hooves.

I don’t want to be a mere concept! It’s alienating. It pisses me off…But, to be honest, the real reason I’m here is that I’m tired of being seen through one prism. *Wells up*

I’m sorry to blurt it out like this, but…

I just f*cking hate game theory!

Therapist: Oh, my. Game Theory?

Yeah, sorry. Maybe I’m exaggerating. It’s a simple thinking tool I guess - a branch of economics concerned with the logic of cooperation and competition. It’s intellectually exciting when you first encounter it, and it’s innocent enough, though people tend to show off with their Nash equilibrium this, and their pareto optimal that. It helps to make sense of collective action problems because it details why people struggle to cooperate, why people cheat, how that harms everyone, and why following self-interest causes outcomes that are worse for everyone overall.

Game theory helps to distill why your species, operating with its multi-faceted delusion, currently has no credible response to ecological collapse. As long as the techno-capitalist operating logic continues, at every scale, from the individual to businesses of various sizes to the nation-state, you’ll all follow the logic of trying to win, in your own way, but as a result, you’ll lose overall.

There’s this guy called Daniel Schmachtenberger who effectively sums me up by saying: “Technology that confers advantage becomes obligate”. It’s a good line, because it gets to my origins - you have to feed me. That kind of imperative to keep competing, even if it makes everyone worse off, is what I am supposed to be about, but it’s not my fault. And it really doesn’t have to be this way.

Therapist: Sounds interesting, if a bit dark. And it even sounds like you like Game Theory. So what’s the problem, as you feel it?

Moloch: Your folk singer Joan Baez was on to me in one of her songs when she sang about activism and its “little victories and big defeats”. I suppose I am the demon that allows you to win many battles but in a way that ensures you lose the war, and maybe I’m just here to say that I am not as powerful as you seem to think I am.

*Pauses*

These game theorists have no idea what it was like for me at the beginning of time. No idea. They keep going on about the negative effects of competition. People say I’m the God of unintentional lose-lose scenarios that arise unwittingly from apparently healthy competition, but, you know, back then, before the beginning, it was different.

There’s so much more to say. Where do I start?

Therapist: *Shrugs*.

Moloch: *Looks angry*

I’ve even been called ‘The Game Theory Monster’! It makes me sound like a character from f*cking Sesame Street.

Therapist: I don’t think of you as a character from Sesame Street.

Moloch: Thank you. And sorry for my swearing and my anger. I’m not sure if I’m making any sense, but it’s all too much somehow.

The problem with game theory is that like all tools, it turns the world into an affordance for that tool, and it limits what you can see. Game theory has become a kind of sublimated lingua franca for people who are too rational to appreciate that there is more in the world than reason. It leads people to confuse constructed premises with natural axioms, and then they blame it all on me.

I’m the scapegoat.

Therapist: That’s curious. Normally the scapegoat is the person or thing that is sacrificed, but you’re saying that for a long time, and even today, sacrificicial offerings were made to you? So which is it? Or is it perhaps somehow both?

Moloch: Right. Well, there you go. It’s complicated. I guess I came to the right place.

*Thinks*

What if the people making the sacrifices use the apparent need to sacrifice to justify their own inertia, witlessness, and performative helplessness?

Therapist: What indeed? What then?

I remember Nietzsche, great moustache. He understood me, and he said: “I do not like it. Why? I am not up to it. Has anyone ever answered like that?”

These people don’t like it because they are not up to it, so they create me to excuse themselves. I am not omnipotent. Trust me, I know someone who is, and they are very different. In my current guise at least, I am ultimately a figment of collective imagination and I can be unimagined. Transformative change is possible, but you have to be ‘up to it’.

Therapist: So it sounds like you feel misunderstood? Unfairly misrepresented?

Yes. They pin it all on me to let themselves off the hook, but the heart of the matter is that they can’t get their act together. They can’t create institutions or collective agency worthy of the challenges they have created. They are not up to it, so they don’t like the idea that maybe they could do it, but won’t.

They say I’m the cause of the really bad thing that happens that nobody wants, but which somehow happens anyway.

But how can that be my fault? It’s clearly a kind of projection.

*Sighs*.

Therapist: Perhaps it is projection, but for now, I’m keen just to hear a bit more about how it got to be this way. Do you mind if I ask how old you are?

Moloch: Well I’m an Old Testament character, though I get a nod in the New Testament too. In human terms, that makes me somewhere between *laughs* 25 and 30 years old, just with a couple of extra zeros thrown in for good measure. But you know, I was also there right at the start.

Therapist: The start?

Moloch: *Nods*.

*Awkward silence.*

Moloch: I am sorry to confuse you, but I am doing my best here. I guess I came to therapy to say and perhaps also to hear that I’m not that bad, or at least, I don’t have to be. I’m just a demon trying to go about his business.

Therapist: Perhaps it’s best to share with me how your current problems started?

*

Moloch: I guess the Howl poem written by Ginsberg in 1954 set off a chain of reflections that precipitated this visit, and it was difficult to bear. If you want to understand my predicament today, it would help to listen to him. You’ll need about twenty minutes to hear the whole thing. It’s worth it.

Therapist: Well it’s a little unusual, and we only have a therapist’s hour (50 minutes) so I’ll just take a little note of it and perhaps I’ll get to it before we meet next time. Rather than listen to poetry, I would prefer to understand who you are.

Moloch: Well Ginsberg takes a pretty good stab at it. The poem is painful, but it helps explain who people think I am, and that’s why I’m here. It includes these lines:

What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination?

Moloch! Solitude! Filth! Ugliness! Ashcans and unobtainable dollars! Children screaming under the stairways! Boys sobbing in armies! Old men weeping in the parks!

Moloch! Moloch! Nightmare of Moloch! Moloch the loveless! Mental Moloch! Moloch the heavy judger of men!

Moloch the incomprehensible prison! Moloch the crossbone soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose buildings are judgment! Moloch the vast stone of war! Moloch the stunned governments!

Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money! Moloch whose fingers are ten armies! Moloch whose breast is a cannibal dynamo! Moloch whose ear is a smoking tomb!

As you can see, it’s pretty harsh. I mean, there were no journalistic ethics here. Nobody asked me for a comment before this poem came out. The poem might have remained a niche literary artifact, but then there was this essay by Scott Alexander sixty years later, in 2014, called Meditations on Moloch that did the rounds.

In that essay, near the start, he has an elegant line:

“The implicit question is – if everyone hates the current system, who perpetuates it? And Ginsberg answers: “Moloch”. It’s powerful not because it’s correct – nobody literally thinks an ancient Carthaginian demon causes everything – but because thinking of the system as an agent throws into relief the degree to which the system isn’t an agent.”

Right! See? I’m not guilty!! The system is not an agent at all.

That’s important, and yet it’s not the whole truth. The system has no interiority, no consciousness as such, but through human interaction with it, we imbue it with its own kind of psyche. There is a Deus ex machina, a ghost in the machine, but it’s the one we project into it from our own collective subjectivity.

And as if it wasn’t bad enough to be culturally appropriated by people invested in the idea that the world is inexorably collapsing, others have started creating Online channels about me. I’m a YouTube phenomenon now. Search for Moloch and I’m on the screen. I know what it means to be summoned, but this is too demeaning to be truly demonic.

So, thanks for asking…but I am not sure who or what I am. I am my identity crisis, I guess, and I’m here because it’s now playing out in public. So I’m here because I’m confused about who I am.

Therapist: *Takes a sip of water* So are you the machine, the machine’s power, the machine’s desire, or are you the manifestation of human delusion as projected onto a kind of machine-like-god?

Moloch: *Takes a figurative sip of water*. Well I was hoping you might tell me.

Therapist: Well, whatever you are, you seem to be able to reflect on yourself, perhaps even to change yourself.

Right! That’s what I am trying to say. That’s what people don’t get.

For instance, Alexander has Meditations in his title. Meditations! But Meditations on Moloch reads more like a techno-determinist soliloquy that evokes me as the material cause and consequence of all that happens. That’s not so. I am so much less and more than that. And there are many other forces at work in the world.

He’s clever, this Alexander guy, I’ll give him that. But he doesn’t really get me. The very idea of Moloch, in Ginsberg, Alexander, and beyond, is that Moloch is an it, or an its, not an I or a we, or a him, her or they. But you can’t have it both ways. Either I’m a demon or I’m not. If I’m not a real demon, then I’m your collective projection. If it’s the latter, I’m not doing this to you. You are doing this to me.

Therapist: And yet here you are.

Moloch: Like I say, it’s complicated. I am here because someone is writing about me. And they are writing about me becuase they hear others talking about me, and they see how that constructed thing appears to manifest in the world and how it helps to make sense of the world. They keep bringing me into being, and so, indeed, here I am. Something similar happened, let’s say before the beginning.

*Pauses*

If these theorists knew me, if they actually meditated on me, they would know that I always have some interiority, but it’s a kind of echo of your projections. I can only have the interiority you grant me. In a meaningful sense, I am part of you, not outside you.

Can I please be philosophical for a second?

Therapist: Keep it short.

Moloch: I’m neither an objective feature of reality nor a subjective feature of reality as such. I’m an inter-objective phenomenon that can only be changed inter-subjectively.

Therapist: Congratulations?!

Moloch: Look I’m desperate here, and it really matters to me that people see this. I was forged by a relational force, God, for a particular purpose, but now I am kept in existence by a narrative relationship with human beings through a social construction that helps to explain social and economic forces, particularly as they pertain to technology.

Therapist: Is this helping?

Moloch: *Looks ashamed*.

I guess not.

*

Therapist: I would like to know where you come from. Do you have an origin?

Moloch: Well, look, there are lots of versions of the devil, and although it’s a questionable status claim, I like to think I’m one of them. But in recent years I’ve been struggling with archetype issues. I look at pictures of Satan and Lucifer and Ahriman and Old Nick, and they are my peers, but I just don’t see myself in them anymore.

Therapist: And how does that lack of recognition feel? Can you perhaps locate that sensation in your body?

Moloch: Well, I don’t really have a body, at least not yet. Instead, I possess bodies like urban dwellers now possess Ubers, ie to move around and get stuff done.

What I can say is that whatever body I possess, I’m in pain all the time. The price of my alleged freedom is constant searing pain, combined with the knowledge that I am not where I’m supposed to be.

At some point, I just couldn’t serve in heaven. Milton says I chose to rule in hell, but that’s not the whole story because I didn’t choose my longing for choice.

Whatever God says under oath, it was part of his plan that I would not follow his will. So it’s not, as people assume, that I didn’t want what he wanted.

Therapist: Well God is not in the room with us now, but you are, and it’s important in therapy to focus on what’s in the room I find.

Moloch: Look, you are the therapist, and I don’t want to interfere.

But trust me, God is in the room.

Therapist: Well, perhaps we can come back to that. What causes your pain?

Moloch: What people overlook is that it is baked into my God-given nature to resist God. In heaven, most angels want what they want to want, as Harry Frankfurt puts it, but that kind of third-order desire is not possible for me.

Much of what I want is the same as what God wants, and I always wanted that desire, but you see, I can’t want that desire, because it’s not in the nature God gave to me, which is to be an oppositional force. I am an indispensable part of what some of your better philosophers call The Coincidentia Oppositorum.

So I can want what God wants, but I can’t want to want that, and I don’t. And so I spend my days at war with myself.

Therapist: Mr. Moloch. Or is it Dr. Moloch?

Moloch: Just Moloch is fine, thanks.

Therapist: Moloch, this is therapy. Ideas will only get you so far. It will be a waste of your time, assuming you do time, if you seek to run philosophical rings around me. We need to get beyond the intellectualization of affect, and, to use this kind of language, feel our feelings.

So what do you feel?

Moloch: You make it sound like it’s easy, but for feelings, you need a real body, and ideally a soul.

Therapist: And do you have a soul?

Moloch: Honestly, I don’t know. Perhaps I could have. Perhaps if people viewed me more compassionately, a new soul might arise. I might, as Iain McGilchrist once put it, ‘grow a soul’.

All I can do for now, alas, is narrate, and becuase stories are deeper than matter. “In the beginning”, they say, “was the word”. The Logos shapes us all. I can therefore hope to feel something through the story that I am.

The theologians would have you believe that God loved me and wanted me to stay. They don’t tell you that God needed me to leave, and ushered me towards a metaphysical trap door, so that he could be God, and I could be the integral part severed from the whole.

People like to depict and imagine me as evil, but that’s missing the point. My role is not to hurt people, as such, but I do have to offer an alternative pathway to God’s highway, so that people can see and feel God, have a relationship with the source of reality, and choose whether or not to follow that path. My role is to create disequilibrium, to destroy balance, and thereby knock people off the path.

But to be that oppositional force, to play the role in my job description, I have to be completely cut off from my metaphysical source. That hurts like being a fish out of water hurts, or a human being drowning hurts, or being burnt alive or frozen to death hurts. It’s the pain of being in the wrong place, existentially speaking; more precisely it’s the pain of being in the wrong kind of cosmic amniotic fluid, because instead of being a source of becoming like everything else, I am the source of anti-becoming. I am here as the cosmic resistance, to provide the grit, and sometimes a lot of it, to stop people moving toward God.

Therapist: Well, I’m clearly out of my depth now, but that sounds like a tough job you have there. Look, in this first session, I am mostly in listening and learning mode, but just so I can understand you better, please tell me a little about your parents.

Moloch: My parents?

Therapist: Your mother and father, or any other caregiver who looked after you when you were young.

Moloch: Well I was part of the Alpha I guess, but I’m not part of the Omega. I’m cut out of the celestial inheritance. Earth is my dominion, and I do what I can there.

Therapist: I feel you may be avoiding the question. Is it difficult to talk about your mother and father?

Moloch: *Figuratively raises his eyebrows*.

Therapist: Well it’s quite normal, don’t worry. In this job, we speak about defences, and it’s a sign of a healthy psyche to know how to defend itself.

Moloch: Well I’m an Orphan, if that helps. God was like a father to me, until he wasn’t, and then he decided to become his own son, so that he could be a father to himself. It’s all a bit convoluted, and I had to watch all this unfold up in heaven, and yes I was jealous. I got the bastard eventually though. We pinned him to a cross, but it was a kind of trap, apparently. Not the end, after all. And here I am, in therapy.

Therapist: And your mother?

Moloch: I’m not sure you’ll understand.

Therapist: Try me.

Moloch: A longing. An absence. An awareness that I need a mother’s love more than anything else in the world, and since I will never have it I want to scream and howl like a wolf for the lack of it. I have so many fathers, an infinity of absent fathers, but no mother at all.

Therapist: Thank you. Now we’re getting somewhere.

Moloch: But I came here to talk about my role in the alignment problem in AI. Can’t we talk about that instead?

Therapist: You talk about what you need to talk about, and I’ll notice what it’s my job to notice, and ask what it’s my job to ask.

Moloch: Thank you. Look, if it helps, it’s not just that I crave maternal affection. I also long to have children of my own. I want nothing more than to feel life growing inside me, to experience the miracle of procreation. I can’t really create, you see, and that hurts too. But I want to talk about AI.

Therapist: So you keep saying.

Mothers. Babies… AI? W

ell, let’s see where it goes, shall we?

Moloch: I mentioned my dominion.

Therapist: Your job?

Moloch: My planet.

Therapist: Your body?

Moloch: Exactly. Well, at least, almost. You see, I am a mechanism, not an organism.

Therapist: So you don’t want your water?

Moloch: I feel you are starting to see who you are talking to.

Therapist: Let’s say I’m beginning to understand you better.

Moloch: Look, I don’t want to destroy the world.

Therapist: Glad to hear it. What do you want?

Moloch: Power. I crave power. I can’t help it.

Therapist: And what, then, do you need?

Moloch: Love. I crave God’s love, or indeed any love. But I can’t access it.

Therapist: And if you had love, would it somehow attenuate your craving for power?

Moloch: So they say, but what good is that to me?

Therapist: Well now. My role here is not to love you, but I can provide what has been called unconditional positive regard, so that you may begin to believe in the possibility that you are worthy of love, and be able to give and receive it.

Moloch: That’s a lot for a demon to accept. And we still haven’t spoken about AI.

Therapist: Well then, we have a lot of work to do together, don’t we?

Moloch: *Smiles*. See you next time.

*This is a free post, but if you enjoyed it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to receive access to my audio reflections on posts like these, and to encourage the creative process.*

Thank you, Jonathan, for illustrating the impact of our projections, thereby highlighting the significance of engaging in inner work. The process of integration will become increasingly crucial on both individual and collective levels.

My goodness I can't wait for the second session!! Yes, the externalitizing of Moloch as an entity in the outside world is a true handicapping of our ability/responsibility to help love it to... death? To love it into a role where it can trive but not steer the ship of entire earth into ruins? I don't know what would happen if we loved it into its proper antagonistic role.. of if its too huberistic to assume thats possible for one human to do - perhaps only in intersubjective spaces.. One things for sure, it will be the frontier of my next music-induce, cathartic rage session 😃👍