On Friday afternoon I took the train from London to Nottingham as if escaping from captivity. I was with my friend Nick, whom I have known since we were schoolboys in Aberdeen. Life felt easier back then. The world was relatively sane, our responsibilities were relatively light, our futures relatively open. Now we are both working parents, tethered to our nests. It’s a life we have chosen, and neither of us wishes it away, but this was a timely bid for freedom. We had sixteen hours of jailbreak together before our responsibilities kicked in again early the next day.

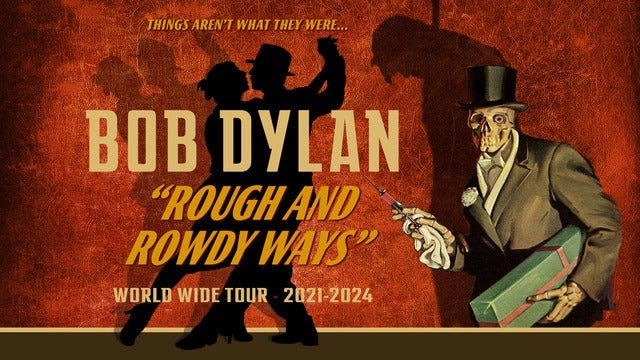

We were heading to a Bob Dylan concert, part of his Rough and Rowdy Ways World tour. Nick had earned the bronze medal of availability in Nottingham after London and Edinburgh sold out almost immediately. It takes time to create time that matters, and courage to re-prioritise pleasure, so I am grateful for the very notion of the trip, and delighted that it happened.

Adult friendship is often undervalued and neglected, which is weird because there are few things so obviously good for us.1 It felt great to be a different kind of self for a while. They say old friends are the best, and I think that’s because so much goes without saying. There is a relief in not having to narrate who we are all over again. There is a bond in already knowing the crosses each other has had to bear. There is oxygen in not having to pretend to be someone other than the confusion that we are. Memories of specific details allow for an arcana of in-jokes that live as if in folk memory. This time we created a new one, with the sincere irony of whisky and cigars overlooking the city at the end of the day, accompanied by two packets of Quavers and some fruit cake from home.

There is a commendable no-phone policy at Dylan concerts, so we all surrendered our phones like the weapons of mass destruction that they are, and we placed them into a pouch, shields for our minds stuffed into the unsuspected battlefield of our pockets. The pouches can only be unlocked by staff members when the crowd disperses at the end, a curious moment when we voluntarily re-submit to the fate of digital atomisation that now connects us.

So I was one of ten thousand people who were liberated for a couple of hours. I have no photographs of the capacity crowd at the Nottingham Arena and, mercifully, did not feel obliged to zoom in for a blurry image of Dylan on stage.

You had to be there.

I discovered Bob Dylan in my early twenties and listened to his earlier songs repeatedly to metabolise the lyrics. A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall (1962) and Chimes of Freedom (1964), come to mind, but there were other lesser-known tracks like To Ramona (1964) and I Shall be Free no. 10 (1971) that I never tire of. Dylan won the Nobel Prize for literature, no less, in 2016, "for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition". His music has evolved over six decades, and I don’t know all of it, but regardless of the genre, his lyrics are invariably prophetic, subversive, fabulous, and surreal. While Dylan is a genius songwriter, the lyrics often seem to come through him rather than originate from him. He acknowledges as much in this short clip from a relatively recent interview.

So when I hear Dylan sing: “And the one-eyed undertaker, he blows a feudal horn”, I don’t know what he’s talking about, and I’m not sure he does either, but I feel the truth of it, and I trust the meaning of it.2

And I know “I heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world” was not written with climate collapse in mind, but it speaks to the flooding we recently saw in North Carolina and Spain.

In a 1963 radio interview, Dylan explained another lyric in Hard Rain:

“In the last verse, when I say, ‘the pellets of poison are flooding the waters’, that means all the lies that people get told on their radios and in their newspapers”. Radio and newspapers! Sixty years later the pellets of poison are still flooding our waters, now as deep fake videos and other forms of disinformation.

Bob Dylan is 83. His voice is tentative, erratic, and uneven, but still exquisitely his own. The tones are reassuringly familiar and they connect with fans viscerally, who then wait, knowing dessert is still to come; soon they are swooning over the harmonica, taken on a trip down the foggy ruins of time. In his later years, the fact that his voice was never conventionally sonorous helps, because nobody expects him to hit the high notes - that’s not where the emotional connection is. People are there on a kind of pilgrimage, in solidarity with each other through him; a wayward Sangha looking to a reluctant Buddha for his oblique Dharma. Many attend simply to say that they saw him, to pay homage to what his music has meant to them over the years.

We all have our favourite classic songs, but Dylan is notorious for refusing to play what the crowd craves to hear. Mostly he plays new material, unwilling to be complicit in the indulgence of nostalgia. And yet he does cater to it a bit, as the concert’s setlist shows.3 After we left The Arena, about a hundred people assembled around a smaller street arena created by a busker. Here’s a twenty-second clip of “It ain’t me, Babe” where your scribe breaks the fourth wall.

I’m sorry that the street scene felt a little too rough and rowdy to get the busker’s name. I wanted to ask him if he does this captive-market-after-show-nostalgia-fest-gig for a living. He played lots of the classics, like Blowing in the Wind, The-Times-they are-a-Changing, Mr. Tambourine Man, The Hurricane, It Ain’t Me Babe. The crowd dutifully forgives Dylan for not playing these songs, but we still long for them, so it felt as if the busker was providing an emergency community service.

**

The official concert ended with a song I had never heard before - Every Grain of Sand. Dylan has a vast canon, but apparently, this one is among his most famous. It was written in 1981 when Dylan was about forty and the song is influenced by Blake’s poetry and Dylan’s Christian journey, and it has stood the test of time. Details of the song can be found here and the verified lyrics are here, but I want to focus on one line in particular that jumped out at me:

Don’t have the inclination to look back on any mistake

Like Cain, I now behold this chain of events that I must break

In the fury of the moment I can see the Master’s hand

In every leaf that trembles, in every grain of sand.-Bob Dylan, Every Grain of Sand (1981)

All these lines are evocative, and the last line makes me think of the idea that the essence of the sacred lies in uniqueness; a recognition that just as the many are profoundly one, the one is profoundly many.

Yet on the night I was most struck by the injunction to behold this chain of events in the context of what’s happening in the world, not least Trump’s re-election, the destruction of Gaza, and recent climate catastrophes. There is a lot of scrambling going on, not beholding, but scrambling. Scrambling to reorient our sense of perspective and agency. So the idea that we must break with causal forces is powerful because it implies that the scrambling is part of the problem, but to get there we first have to behold - not just look, but attend, contemplate, inhabit…

At first, I wanted to ignore ‘Like Cain’, because it felt like an awkward detail, but it wouldn’t leave me alone, and attending to it is an integral part of the beholding.

Why Cain? The book of Genesis is allegory not history, told as a story in which Cain was the first child of Adam and Eve. Cain killed the second natural born human, his brother, Abel, through envy, a misplaced sense of entitlement, and a lack of awareness of consequences. Some believe this story speaks to the roots of war throughout human history. While it might seem cute that the first naked humans had some trouble with an apple and a snake, it’s not cute that the story of the human family starts with murder.

I’ll leave it to Theologians (or even Jordan Peterson on a relatively good day) to make fuller sense of it, but to give some idea, the names are significant, with Cain meaning something like acquisitve and Abel meaning something like empty. And after God discovers the fratricide, Cain is sent into exile, but he is also protected with a mark, which is at once a sign of sin but also the allegiance of God. Cain is lost, but not forsaken. And then there’s the importance of land, what grows upon it and how. The blood of Abel that Cain spilt leads to corruption, and does not offer the spiritual irrigation offered by the blood of Christ, but it contextualises it in important ways. What is explored here is not just sacrifice but different kinds of sacrifice, including the ultimate sacrifice of the cruxifiction and what that means for ending cycles of memetic violence and the possibility of peace and redemption. Cain’s fate is also about the rewards of human effort, the importance of wholehearted offerings, second chances not taken, and the moral foundations of civilisation.

It’s too much for now.

What I can say, with Dylan’s contemporary relevance in mind, is that Cain represents our reality-avoidant culture, which is another way to understand separation from God, and the idea of sin understood as the human propensity to f*** things up (tHPtFtU).4

Just as Cain has to contend with the weight of the past, and all that he has done, we all do. We are all caught up in hysteresis, the apparently inexorable influence of the past on the present. When Ganfalf says in Lord of the Rings: “Understand, Frodo, things are now in motion that cannot be undone” he is talking about hysteresis. To illustrate, I remember a Rory Stewart Lecture that begins with a ‘chain of events’ that he believes has precipitated the collapse of liberal democracy, includling the bogus basis for the war in Iraq, the financial crash, social media and the internet enabled smartphone, and the failure of international institutions to deal with climate collapse.

‘This chain of events’ has broader meaning. The pogroms are implicit in The Balfour Declaration and The Balfour Declaration lives on in the destruction of Gaza. Barack Obama’s joke at Trump’s expense in the White House Dinner in 2011 did not cause the mass deportations that are now threatened, but it is implicated. The fossil fuel industry created extraordinary wealth for decades, but it is now literally killing people, albeit indirectly through climate impacts, which the law could show if only it would behold, reckon with complexity, and update its conceptions of agency and causation. Hysteresis can even be understood as a secular conception of Karma. It is not just the past catching up with you, but the past that is already baked into the future. That is why, for instance, we are not yet at 1.5 degrees celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, but it is guaranteed that we will be, due to prevailing energy demand and endemic inertia in the global system. It is already there.

And yet it’s worth looking again at Dylan’s lyrics: “Don’t have the inclination to look back on any mistake”, he says.

The need to ‘behold’ ‘this chain of events’ goes beyond correcting past wrongs or learning from particular transgressions (‘any mistake’). What is described here is not regret at careless acts or roads not taken, but a deeper reckoning with the human predicament. What we ‘must break’ is the root cause of the problem, which is delusion, our wonky relationship to reality.

Again there is too much to say, but I love the Robin Williams joke:

“Reality? What a concept!”

Reality is not just what is ‘out there’ objectively, or ‘in here’ subjectively, or even ‘between us’ inter-subjectively and inter-objectively; it is all of these things which have their own ontologies, epistemologies and axiologies; I believe they are related but irreducible to each other. Improving our relationship to reality is therefore about improving the alignment between what Perspectiva calls our systems, souls and society.

That’s the relatively dry, if important, philosophical angle, but there is also a more psychological and emotional point. Namely, we need to forgive ourselves if we are to have any chance of transforming ourselves or the world. Otherwise, we are just trapped in the persistence of resistance, projecting onto others, blind to our immunity to change, inadvertently chasing our own tail on an epic scale.

As psychotherapist Carl Rogers once put it:

The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I change.

I think that means accepting that we have already failed on climate change, and that means not trying harder but thinking differently. Transformative acceptance also means accepting that representative democracy as we have known it has already broken down because our education and media systems are no longer fit for that purpose. That doesn’t mean giving up on democracy, but reconceiving it, and renewing it through the roots that matter most.

What does it mean then, in the fury of the moment, to behold this chain of events, and break them?

I don’t know.

But that’s the question.

In the meantime, here’s the song.

Liz Oldfield - a friend - even calls friendship her theory of change.

A comment below indicates that the lyric is actually ‘futile horn’, which makes slightly more sense, though it’s still cryptic. The way it is sung by Dylan sounds more like ‘few-dal’ than few-tile to my ear, even after knowing this detail. There is an overlap with “midnight’s broken toe” in note three below in the sense that I am slightly disappointed to find the lyric is less ambiguous and surreal than I originally thought…

This refusal to be motivated by pleasing the audience may be part of any creative excellence. Dylan succeeds in not lapsing into schmaltzy sentimentality because he is Protean, always somehow evading conceptual or emotional capture. For instance, the lyric that I and millions of others heard and sang as “Far between sundown’s finish, and midnight’s broken toe” is actually “midnight’s broken toll”. I felt visceral disappointment when I learnt that. Dylan can hardly be blamed for that, but more generally he insisted on disappointing people; he was not in the business of cow-towing to the audience’s desires for things to be a certain way. Dylan’s recent concerts vary enormously in quality, with some lasting merely ninety minutes and featuring no vocals. I am not a music critic, but I was relatively lucky on Friday, feeling lost *in* the music, even though it was new to me. Dylan spent most of his time behind the keyboard and came out to show himself periodically, always to critical acclaim - it reminded me of a game of peekaboo played with babies.

The human propensity to fuck things up is Francis Spufford’s definition of sin in his brilliant book Unapologetic.

Wow, man. This is beautiful.

This particular verse from "Every Grain of Sand" is nestled quietly among the rest; but it's the one that always jumps out on me. He closed with this song when I saw him last year in Asheville, too. It's mysterious what these songs have meant for some of us.

PS: There's a bootleg recording out there, which I prefer to the album version. It's simpler, somehow frailer. You can hear a dog barking in the background.

Agree with John, blown away by this piece.