Starting in Mysticism; Ending in Politics

Charles Peguy, Bruno Latour, and the curious case of 'amodernism'.

Everything begins in mysticism and ends in Politics. - Charles Peguy

Since the age of about ten, I’ve been drawn to quotations like this one, but in recent years I’ve become keen to learn more about the person behind choice words. Quotations now spread all-too-easily online, and often get distorted as they drift further from their source in space and time, but the person who said or wrote them is somehow anchored, always unique and singular, speaking from somewhere at some time, and for some reason.

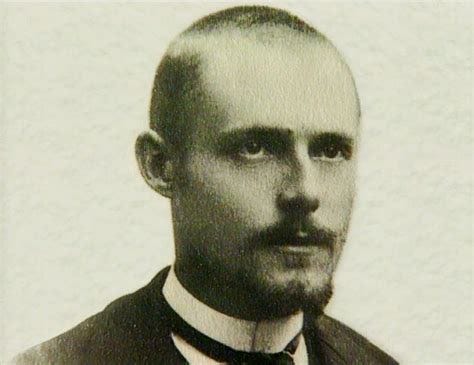

Charles Peguy was a French Catholic Poet who penned those lines - everything starts in mysticism and ends in politics - in his book Notre Jeunesse, ‘Our Youth’, which was published in 1910. Peguy (1873-1914) was a contemporary of the sociologist Emile Durkheim and the philosopher Henri Bergson, though not as well known as either, perhaps because he died just as his intellectual contribution was beginning to peak, at the tender age of 41.

True to the aphorism for which he is perhaps best known, Peguy’s life ended in politics. He enlisted to fight in the first world war where he led a French charge against the Germans; but like many such charges it led to nowhere but death. The so-called Great War was pointless, even by the standards of most wars, killing about 40 million people for je ne sais quoi.

So much for endings. Peguy’s life, like all lives, began in a kind of mysticism. Wittengenstein argued that it’s now how life is, but that it is that is mystical. And while this thought applies to life-as-existence in general, it also speaks to the uniqueness of each life, a notion captured by the Zen koan to “Show me your face before you were born". That koan is supposed to be difficult to parse, while sitting with the difficulty is supposed to help us begin to see our original face in the ultimate source of life, which is something other than a reproductive chain of events. Indeed Rowan Williams suggests that one of things a religious attitude to life gives us is the sense that “we are not our own origin” - I certainly feel that way. But I can imagine atheistic and non-relgious friends being quick to argue that religion has no monopoly on the mystical, which can also be considered an umediated experience or direct perception of reality that is in principle available to anyone.

Once more, with feeling: everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics.

Perhaps part of the problem is that so much of life now begins in politics. In my conversation with Oliver Burkeman at the Realisation festival in June I was struck by his suggestion (he was quoting someone) that for all the talk of cultural and political polarisation the counter-point is not just that beyond the noisy extremes most people appear to be relatively unpolarised. The deeper point is that it’s entirely possible to spend quality time with people and not talk about poltics at all. If you want to feel less divided, try to spend time doing things that are grounded in shared experience not in divergent opinion. We share a prior unity, as Peguy’s line intimates, and though such unity will and should fracture and divide over time, we don’t have to start from there. People are always saying that ‘everything is one’, but it’s equally true that one is everything.

This point applies to politics too, which often forgets about the pre-politicsl unity and and by-passes mysticism entirely. Moreover, the question of the ultimate nature, meaning and purpose of life is rarely considered part of the political conversation, which is why I was so impresed by Tim Jackson’s book Post Growth which looks at them directly. This challenge of reimagining the world from first principles, navigating the spiritual and the political, is central to my work with Perspectiva, the charity I co-founded in 2016 and now direct on a day-to-day basis. We say that our work is about understanding the relationship between systems, souls and society in theory and practice. One way of restating that, and only one way, is this: if Peguy is right that everything starts in mysticism and ends in politics, what follows?

I have not read much of Peguy’s primary texts, but I hope life allows me to soon. A Hedgehog Review article on a biography of Peguy contends that he had his own school of thought called Amodernism. I am purportedly a metamodernist which is another conversation, but amodernism is one of many composite words with a prefix before ‘modernist/m’ and is definitely among the more intuitively attractive ones. In my essay on metamodernism I briskly try to define modernism and postmodernism as part of the conceptual context, and it’s worth sharing what I wrote about modernism there so we can better understand Peguy’s negation.

The term ‘modern’ is derived from the Latin modo and simply means ‘of today’, distinguishing whatever is contemporary from earlier times. Modernity refers to our contemporary civilisation built over the last 400 years or so through scientific, industrial and technological revolutions, but what makes modernity is not just method or machines. We are not, as sociologist Peter Berger puts it, ancient Egyptians in airplanes, not least because so many of us are future-oriented, at least in our younger years. Indeed Habermas’s description of modernity is precisely about that. In The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, he writes: ‘the concept of modernity expresses the conviction that the future has already begun: it is the epoch that lives for the future, that opens itself up to the novelty of the future.’ As we open up to the future, and as the world changes, we change too. And so modernism, although voluminous and outrageously ambiguous, refers to the worldviews that arose from human culture stewing in the juices of modernity for decades. Modernism expressed itself in art, architecture and literature and evolved into political institutions and ideologies. Science is quintessentially modern but capitalism and communism are also modernist endeavours, and so is the organised aspect of religion and human rights law. Perhaps most relevant for current purposes is that modernism entails an irresolute process of secularisation and also the growth of civic and commercial institutions powered by bureaucratic and instrumental rationality and an exploitative relationship to nature. Modernism is therefore about presumed material and scientific progress, but it is often accused of wearing blinkers about its collateral damage. For instance colonialism, slavery and fossil fuels drove much of modernism’s so-called ‘progress’. In a related sense, in Habermas’s later work, Modernity: An Unfinished Project, he argues that modernity is characterised by the separation of truth, beauty and goodness; of science, art and morality. That separation of our value spheres was a source of fragmentation and alienation that lived on in postmodernism, and part of the purpose of metamodern metaphysics mentioned below is to somehow bring them back together.

To be amodern then is to deny the central importance of the claims included in this paragraph. To be amodern, I guess, is to ask: what if using modernity and modernist as the fulcrum around which to locate ourselves is a fundamental part of the problem? Peguy seemed to think that, and his thought featured prominently in the Doctorate of Bruno Latour who sadly passed away earlier this week. Latour brilliantly combines science, politics and religion - I loved Down to Earth(2018) especially - and his intellectual debt to Peguy helps me make sense of amodernism as an idea. Perhaps Latour’s most famous argument (also one of his book titles) is that We Have Never Been Modern.

Latour means many things by that statement: that modernity is not as distinct an epoch as is claimed, that the assumption of progress is questionable, that the conceptual maps of the modern world are not true to the lived experience of the territory it is supposed to describe; and so mabye we are not so special after all, and maybe the conceptual and institutional distinctions and divisions that characterise modernity are not beacons of progress, but also or rather ways of systemtically denaturing and disenchanting the world. In light of Latour’s claim that we have never been modern, the fact that Peguy - an amodernist who believed everything starts in mysticism and ends in politics - had a formative influence on Latour makes a lot of sense.

Peguy seems to have noticed back in the very early 20th century that there is a deep problem within the liberal/reactionary bifurcation, namely that by imagining there is such a thing as modernity we invent reasons to be for and against it too, and this leads to a loss of overall perspective and undermines cooperation. In Joseph Ananda Josephson Storm’s recent book on Metamodernism which I currently reading, there is a particularly brilliant chapter on some of the major problems today in academic social theory, including the apparent non-existence and yet conceptual necessity of objects of inquiry like modernity. I cannot resolve that question now, but suffice to say that while metamodernism may place you in a certain kind of reflexive relationship to modernism, amodernism seems more likely to refuse to be part of that kind of relationship on the grounds that it’s ultimately unreal. Here’s an extract from the Hedgehog review article that speaks to Peguy trying to escape the progressive/reactionary juxtaposition:

Instead of such immanentist ends of history, Péguy hoped for an era of “competence,” one that would incorporate a healthy regard for liberal ideals and empirical science (including a skepticism about the limits of the latter) with real tolerance for a variety of deep metaphysical commitments, including ones admitting of the transcendent and the mystical. Such “metaphysical federalism,” Maguire writes, “would limit the excesses of a constrictive metaphysical hegemony in contemporary culture.” Péguy believed that advocates of metaphysical hegemony on both the left and the right were foes of the liberal arts that were indispensable to republican democracy. Joined invisibly in their shared immanentism, these hegemonists embodied the deep intolerance of late modernity—and therefore were to be exposed and resisted for what they so dangerously espoused. Call it one of the great tragedies of modernity that the warnings of this clear and prophetic voice were lost not just to his time but to the century that has since unfolded.

This notion that immanentism is part of the problem is subtle but profoundly important. Peguy is keen to keep a place for transcendence in political conversations, but that place should not be subsumed by the trappings of convention, hierarchy and organised religion. The problem for the progressive is that they don’t know how to speak of the transcendent; the problem for the reactionary is that they think the transcendent is theirs and theirs alone to speak about. This conundrum reminds me of an outstanding essay on Blake’s imagination by my colleague and friend Mark Vernon where he distinguishes between four main forms of imagination, with the latter, known as Eternity, as the ultimate lodestar.

Eternity likewise casts a different light on contemporary concerns about ecological devastation. It shows that the material world alone is too small for us. Our capacity for transcendence means that we are creatures of infinity. We can notice ‘Heaven in a Wild Flower’ and ‘Eternity in an hour’, though the perception should also be a warning; as Blake stressed: ‘More! More! is the cry of a mistaken soul, less than All cannot satisfy Man.’

His vision for ecology is, therefore, not one of managed exploitation (Ulro), managed consumption (Generation), or even managed cooperation (Beulah), but instead one aimed at radically extending awareness of the ecologies of which we’re a part. It means embracing not just the environments and organisms studied by the natural sciences but the divine intelligences appreciated by the visionaries, plus a panoply of gods, spirits and daemons that our ancestors took as read.

I suspect it might be fair to say that Blake was an amodernist. To start with modernism, after all, is to risk losing sight of Eternity, and risks making the mistake of starting with politics. A relationship to modernism is no bad thing, even if modernism is ultimately unreal, but it might not work well as a fundamental premise for individual or collective life.

Perhaps Charles Peguy is right that when trying to fashion a shared world we want to live in, it may be better to start from a perspective that has nothing to do with ‘modernity’, but with mysticism, a direct experience of our relationship to reality as such.