The folk wisdom “when the student is ready the teacher will appear” has become an internet meme, but we shouldn’t hold that against it. I believe in the idea’s intellectual dignity. Contrary to what a quick Google search will suggest, the statement is probably not an African proverb, it seems too straightforward for Lao Tzu, it is one of the more obvious Fake Buddha Quotes, and if a version of these words is in the Kabbalah, they are beyond my sight. The idea does have an origin in Theosophy, with a relatively solid reference on page 48 of the book Light on the Path by Mabel Collins from the late nineteenth century, and while there is probably more to the provenance of the idea, I wanted you to know that I am not just making it up.

We become ready for certain things only when time has had its way with us. Life happens, years go by, our receptivity ripens and suddenly, or so it seems, we can hear, understand and feel things that had previously passed us by. In my case, at the not entirely tender age of 47, a spiritual teacher seems to have appeared, and I feel a renewed readiness to learn.

This post is mostly an introduction to Cynthia Bourgeault and why her work has come to mean so much to me (it feels most natural to call her ‘Cynthia’ here, but she is also Dr. Bourgealt and an Episcopal Priest). In the context of claims of a Christian revival, where legions of men and their beards are apparently finding Jesus and keen to tell the internet about it, I should start by saying why that’s not what I am doing here.

What I am doing neither amounts to ‘Christianity is the answer’ nor ‘Christianity is not the answer’. Instead, I seek to outline my enthusiasm for a discerning set of lateral and transformative perspectives from within the world’s largest religion; by doing so I hope to make an invitation to the questions and the answers a much roomier proposition.

***

I had been aware of Cynthia Bourgeault for a few years, and remember being charmed by the glistening water and boat ride that greets you on her website. However, when I heard Cynthia described as a ‘Christian mystic’ the adjective overshadowed the noun and I wasn’t ready to explore her work further.

I struggle with Christianity’s subsumptive character. The premise of the unique historical particularity of Jesus creates a mantle of revealed truth that always risks fostering pride by association. I am generalising here, but in my experience other religions and worldviews are welcomed by Christians not so much as challenging or complimentary truth claims, but more like cultural curiosities to be gently jettisoned or warmly assimilated within a greater Christian vision.

It is not trivial to be religiously Christian in a truly pluralist way, in which you accept that other religions offer equally good pathways to God. As I have indicated elsewhere, the idea that Jesus is a unique cosmic lynchpin should not be ignored, and nor can it lightly be set aside. If part of the point of God becoming human was to know us through embodied participation in what it is like to be human, that can only happen by reckoning with defining features of human existence, namely our uniqueness and our mortality. I don’t want to get high on axioms, but it seems to me that God cannot know what it is to be human unless he knows what it’s like to be a particular person in a particular place at a particular time. That appears to mean that for the incarnation of God to fulfil the cosmic purpose of ‘becoming one of us’ it can only happen once. It follows that ‘the scandal of particularly’ that is Jesus has moral weight, a kind of philosophical coherence, and therefore poses an intellectual challenge. The Mythos and Ethos and Pathos of the Christian religion may permeate the modern world, but in terms of Logos, it seems to me that the historical question - did it actually happen? - is worthy of our attention (even if ‘it’ needs some clarification). “I don’t know” is my answer, but that’s another way of saying maybe, and the question lives on.

So I am not a Christian, but nor am a-Christian or anti-Christian and it would be foolish to be so. Indeed, perhaps the main personal impact of the work I led on public engagement with spirituality a decade ago was that I came to appreciate the wellsprings of truth, beauty and goodness within my own cultural tradition. As a result, I have taken time in churches, in prayer, with the Bible and to some extent in community, to give my cultural and religious inheritance a chance to do its work on me. A highlight was reading Francis Spufford’s brilliant book Unapologetic, where I thought: ‘Wow! If being Christian really feels like that, and allows you to write that well, I’m in.’ But somehow I couldn’t get in. I have only recently realised that I did not actually seek to get in. I believe my path is different. Adjacent perhaps, but distinct.

For a while, I thought maybe I lacked the humility to surrender. Perhaps my life was too comfortable, or the religious conversion experience was just around the corner. But that framing situates everything within a Christian manifold. There’s an evocative moment in the Oscar-winning film Forest Gump when the main protagonist, Forest, is sitting with a weary Lieutenant Dan, a Vietnam veteran, disabled and disillusioned by war, who asks with feigned solemnity:

“Have you found Jesus yet, Gump?”

Forest replies: “I didn’t know I was supposed to be looking for him, sir.”

Lieutenant Dan laughs, as do millions watching, and not for the first time in the movie, Forest’s simplicity breaches the presumptions of the social order. Are there not other things to look for, and other things to find? Do we have to search at all? If God is with us, are he and she and they not all of that?

**

Through reading and merely living, I have become partly Buddhist and Taoist and sympathetic to the coherence of a world without a monotheistic God, or the abracadabra of The Resurrection. Through my marriage of almost two decades, I have also become partly Hindu, and my main spiritual practice for the last twenty-five years, transcendental meditation (TM), comes from the Vedic tradition. I even have an Indian spiritual name, Vivekananda (‘discriminating bliss’). This name feels real, and I talk to Vivekananda sometimes, though in public I am always Jonathan. My spiritual name was acquired in a fire ceremony so that as a white man at large in a land of brown faces, I could enter Guruvayur Temple in Kerala and not look like a wayward tourist. I was not there for Dharshan but because my upper body strength was required to carry our baby son Vishnu who was still being fed by my wife Siva. We were all there in Krishna’s purported abode on Earth to ritualistically discover our weight in bananas. The temple rules are such that to be in that sacred place I had to commit apostasy and renounce my faith in Christianity in a fire ceremony.

They say you never know what you’ve got until it’s gone. I never actually had such faith, but the act of giving up Christianity brought home to me that at some level I will always be Christian. But at what level, exactly? I think at the level that I am willing to stand up for it, as I would hope I could stand up to a bully picking on another child in the playground. There is this saying: “not even good enough to be wrong”. I feel that way about a lot of casual criticisms of Christianity from people who don’t know the religion as a practice, or a community, or a doctrine or an experience. I want to say: You don’t know what you are talking about. You don’t know what you already have. You don’t know what you are disregarding.

At the same time, however, I would like my Christian friends to see that it is possible to explore and experience Christianity with a genuine appetite for God, and find it wanting. That felt sense of the inadequacy of Christianity might simply be a matter of not finding the right church or community, but it might also be related to the stage of history we are in, where we live with the spiritual and material exhaustion of modernity known as the metacrisis. I suspect the kind of spiritual and material renewal now called for will have to be based on much more than a two thousand-year-old story, even if it’s true.

I have been speaking or writing about the importance of understanding the spiritual dimensions of major collective action challenges since around 2013. In that time, I have been looking for a form of spiritual commitment, community and practice that is not a facile ‘spiritual but not religious’ free-for-all, and not so personal or syncretic that the narcissism of small differences prevails. I’ve been looking for a living tradition that remains in wholehearted conversation with other traditions and welcomes a post-conventional sensibility like my own. And, recently, I found Cynthia Bourgeault.

What I sought, and what I believe Cynthia offers, is a credible and beautiful metaphysics that transcends and includes Christianity; offering a worldview that is not Christian in a conventional sense, but not not Christian either. This creative tension is why I feel comfortable saying Cynthia Bourgeault feels like my spiritual teacher, even though I would not describe myself as Christian. The non-Christian elements of her Christianity do not feel synthetic or gratuitous or merely diplomatic; rather they have grown out of decades of dedicated contemplation by a disciplined mind and perceptive heart. Cynthia Bourgeault offers a way of situating the Christian religion within a larger cosmological vision that is capacious and inclusive by design.

***

This ‘appearance’ of a spiritual teacher came about in an unusual way. I heard this esteemed teacher liked a video of me talking about the metacrisis, created by one of her longtime students, Katie Teague. Cynthia has used this video at the beginning of some of her workshops as a way of grounding the practices and discussions that follow in the state of the world we are called to respond to. That’s a deep point of connection and it made me pay attention. I felt flattered of course, but I heard about this before I knew her work. When I say the metacrisis is ultimately a spiritual problem I have some idea what I mean, but I know now from reading her books and listening to her talks that Cynthia has a much richer and fuller sense of it, which is why I am touched by to have been noticed in this way.

The natural next step would be to write an email or try to attend one of her retreats, but I decided I would first get to know her work better. Over the last year, I have read and re-read The Eye of the Heart, The Holy Trinty and the Law of Three, At the Corner of Fourth and Non-Dual, The Wisdom Jesus, The Heart of Centering Prayer, and I listened to her recorded lectures on The Meaning of Mary Magdalene and read her written Lessons on Jean Gebser. I have not yet attended one of her retreats, mostly due to family constraints, but plan to do soon. I believe she is, as they say, the real deal.

‘Bourgealtian Christianity’ is distinctly different from what most people, Christian or not, imagine the premises and parameters and practices of Christianity to be. I cannot do justice to the depth and acuity of her ideas here, and may come back to each of them in more depth if time allows, but I want to offer a taste of what I see as her most important touchstones.

***

Cosmology: The Cosmic Intertidal Zone, and Imaginal Causality

Cynthia begins The Eye of the Heart by quoting Evan Thompson: “Although some illusions are constructions, not all constructions are illusions” and that’s a good way to think of the cosmology that I can only touch on here. It may not be a map that is true to reality, but it is a map informed by our experience of reality that gets us closer to truth.

Cynthia situates our spiritual struggles within an apparently fantastical but eerily plausible celestial (and weirdly chemical and musical) ‘Ray of Creation’ that stems from the Central Asian enigma known as Gurdjieff. Layman Pascal has written a playful new biography of Gurdjieff and describes him as a unique combination of “Indiana Jones, The Buddha, and Borat”, while Cynthia refers to his “inimitable mixture of cosmic truth and pure blarney” (Holy Trinity and the Law of Three, p22).

The influence of Gurdjieff on Bourgeault can hardly be overstated, but it is one influence among many, and she selects from it, and tweaks what she selects with great care; her range of comparable references allows her to see it in perspective and intuit its brilliance and relevance while not getting lost in the ‘blarney’. At first, I thought she might be joking with the way she works with Gurdjieff’s Meglacosmos, but once you realise she is serious, you begin to understand why. This is a cosmology - a story of the nature of the universe - that provides the setting to help build coherence with what Cynthia writes elsewhere (tacitly) about ontology - what exists, epistemology - how we know, and axiology - what’s of value. I believe those four elements together comprise any well-thought-out metaphysics.

The operative principle of this construction is the varying density of The Absolute. She quotes Valentin Tomberg from his Meditations on the Tarot as follows (p17, The Eye of the Heart):

Modern Science has come to understand that matter is only condensed energy….Sooner or later science will discover that what it calls “energy” is only condensed psychic force - which discovery will lead in the end to the establishment of the fact that psychic force is the “condensation”, pure and simple, of consciousness, i.e. spirit.

There’s a lot to interrogate there, but one corollary idea is the reality of an imaginal realm intersecting with our own, inspired by Islamic mystical thought (especially Corbin). On this way of looking at things, if you’ve ever experienced synchronicity you are probably encountering ‘the cosmic intertidal zone’ between ‘World 24’ and ‘World 48’, by which she means between the imaginal realm and earth.

The idea of imaginal causality is that a great deal of what happens on earth happens because of ‘World 24’. Understanding the nature of that causality calls for a fuller vision of the self and an awareness of different kinds of time, a fuller understanding of space, and an appreciation for chiastic patterns. Again, this can feel like a stretch, but I believe it’s a good stretch towards reality rather than away from it.

While (the imaginal) is typically associated with the world of dreams, visions, and prophecy, i.e. a more subtle form, the imaginal…designates a sphere that is not less real but more real than our so-called “objective reality” and whose generative energy can (and does) change the course of events in the world.

I don’t know how much sense any of this can make to those who haven’t read The Eye of the Heart, where the case is built up carefully. What I can say is that considering the relationship between World 24 and World 48 has helped to make sense of my life, especially by normalising those moments where it feels like the universe is winking at me and I have to figure out how best to wink back.

**

Metaphysics: The Law of Three

Cynthia also posits a distinctive ‘Law of Three’ Metaphysics that elucidates the Christian Trinity but is fundamentally free from it; it is also distinct from Hegelian synthesis, and universal in application. She takes 250+ tightly argued pages to explain the law of three, and apologises to the reader for the final third of the book which she describes as an “admittedly eccentric conflation of mystical vision, metaphysical ‘math’, and quasi cosmology.” She adds, “You may wonder what realm of reality I think I’m describing here. I wonder the same thing myself.”

I admire this inquiry into ‘ternary metaphysics’ all the more for the sense that she is reaching beyond her considerable grasp. It is weird and wonderful, but there is a steely coherence within it all, it feels palpably like she is doing the work she alone is meant to do, which is charismatic.

I am not going to try to delve deeply here, but the idea is worth your time, and it is described in eight foundational principles:

In every new arising there are three forces involved; affirming, denying, and reconciling (or affirming, denying and neutralising).

The interweaving of the three produces a fourth in a new dimension.

Affirming, denying and reconciling are not fixed points or permanent essence attributes, but can and do shift and must be discerned situationally.

It is always at the neutralising point that a new triad emerges.

Not any set of three items constitutes a trinity but only those sets in which the three can be seen to be dynamically intertwined according to the stipulations of the Law of Three.

Solutions to impasses generally come by learning how to spot and mediate third force, which is present in every situation but generally hidden.

New arisings according to the Law of Three will generally continue to progress according to the Law of Seven.

The idea of third force is found in religion in the conepte of the Trinity.

Point two is the key operative principle, illustrated for instance with flour and water becoming bread only when fire is added. There are a few more things to note. The law of three apparently applies to all phenomena of all scales “from subatomic to cosmic”. The third force is an independent force and not produced by the first two forces.

Also, Cynthia believes The Law of Three is “Christianity’s hidden driveshaft” that yields “Christianity’s missing feminine”. However, she begins the book The Holy Trinity and the Law of Three by explaining why she feels that ‘feminising the trinity’ by rendering the holy spirit as female does not work. She believes the mistake is to confuse '“the metaphysical principle” with “a doctrinal prop” and thereby miss how the feminine manifests in “time as sequential process” and in “the inherent energy for transformation” that can be found in a metaphysics that is prior to and beyond Christian doctrine, but also therefore within it.

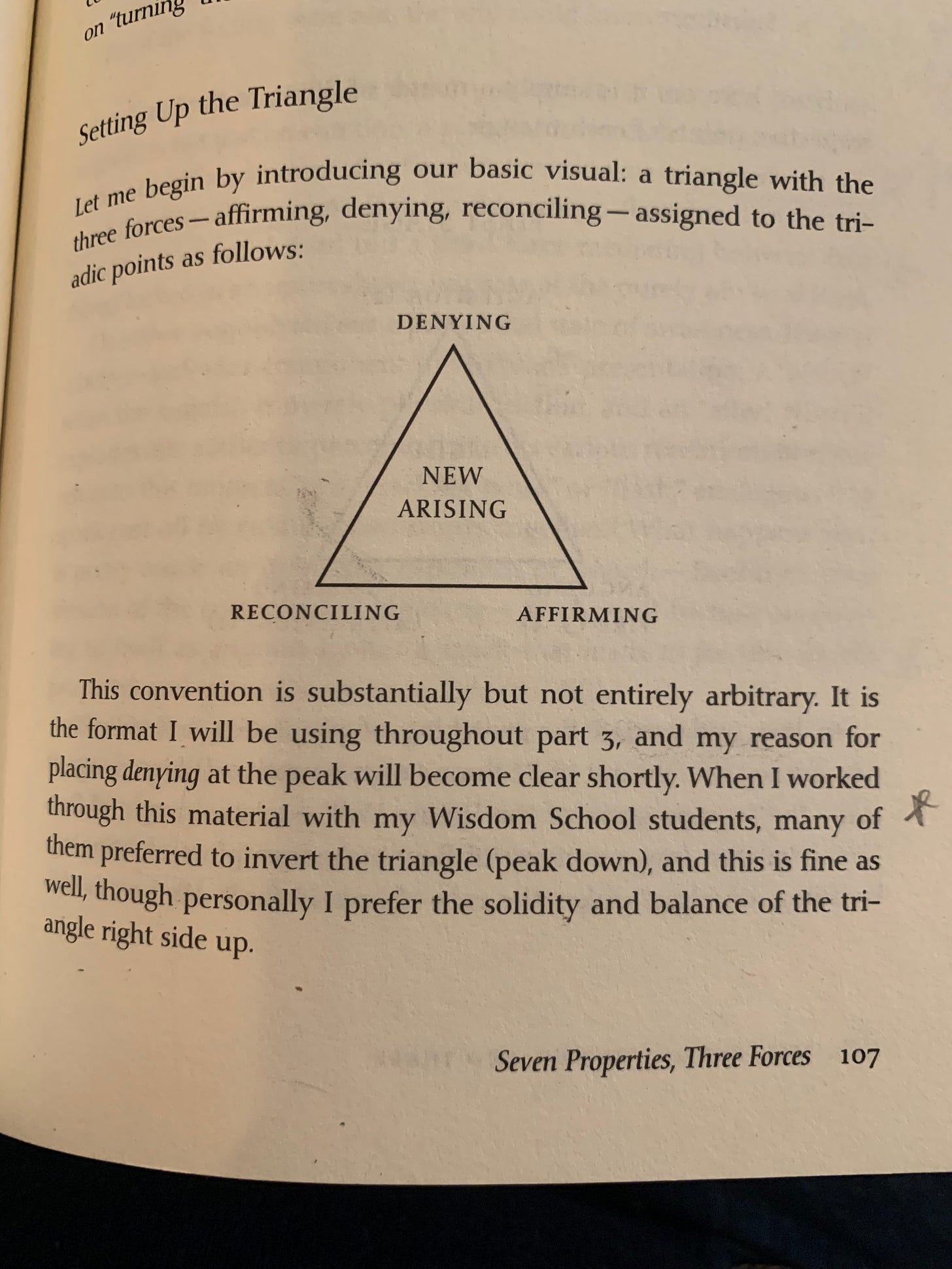

The diagram below from The Holy Trinity and the Law of Three (2013, p107) offers a simple visual, and there are several more of these triangles in the book as the idea deepens.

I don’t know of Cynthia’s politics, but I know from her appreciation of my metacrisis thoughts that she is worldly aware. I believe there is a metapolitical dimension to the law of three, which places creative generativity at the heart of reality. I feel a kind of deep hopefulness in this deep ternary structure - always open and alive - that I don’t feel with the relatively closed and conservative notions of ‘the coincidence of opposites’ or ‘metamodern oscillation’.

**

Practice: Centering prayer. Putting the mind in the heart.

Cynthia’s outlook is grounded in her many years of religious training but her main practice and teaching is Centering Prayer. Though a distinct practice in its own right, with Christian mystical roots in the classic text The Cloud of Unknowing from the 14th century, it can also be viewed as a Christian adaptation of Transcendental Meditation. This is meditation as intention to remain open to what feels like a natural unfolding process within us, rather than attention to anything in particular. The practice is not about petitioning God or improving your mind, but gradually relocating your mind in your heart.

Indeed, Cynthia makes the case for the heart, both figurative and literal as “an organ of perception”, and the place we need to perceive from in order to get beyond the the subject/object duality that distorts perception. Centering Prayer is about cultivating your nervous system so that it moves in that direction. In fact, Cynthia quotes Robert Sardello (approvingly) who writes in his book Silence: The Mystery of Wholeness that “The physical organ of the heart…functions simultaneously as a physical, psychic and spiritual organ”. The heart beats, perceives and connects. She later refers to a famous Biblical line from the Beatitudes in The Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God”. Cynthia adds: “In this one sentence, the whole of the teaching is conveyed”.

**

Religion: Jesus as a Non-dual teacher, Gnostic gospels, Mary Magdalene

Cynthia sees Jesus primarily as a wisdom teacher transmitting non-dual consciousness and metanoia. She is well versed in the synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) and often starts there, but she seems inclined to believe in the validity and transformative potential of many (not all) of the more recently discovered Gnostic gospels from Nag Hammadi in 1945. A very different picture of Jesus emerges from these texts, including a reappraisal of Mary Magdalene as Jesus’s most trusted disciple and what that implies for how relations between men and women might have been different, and might yet be.

In an early chapter of The Wisdom Jesus called ‘Jesus as a Recognition Event’ she writes:

We are living in an era right now which some would call a major paradigm shift, where there’s an opportunity as perhaps there hasn’t been before to really open up the core questions again and ask, “What is that we mean by ‘Christianity’? What is this filter that we’re looking through? Who is this Master we profess to confess in our life as we call ourselves Christian?’

…Jesus is first and foremost a wisdom teacher, a person who clearly emerges out of and works within an ancient tradition called ‘wisdom’, sometimes known as sophia perennis…it is concerned with the transformation of the whole human being…from our animal instincts and egocentricity into love and compassion; from a judgmental and dualistic worldview into a nondual acceptingness…

…I’m mindful here of one of my favourite quotes, attributed to the British writer G.K. Chesterton: “Christianity isn’t a failure; it just hasn’t been tried yet.”

It’s worth adding that Cynthia believes Mary Magdalene is a much more significant figure than we have come to believe. In episode three of her ‘The Meaning of Mary Magdalene’ course she laments the way the history of Christian doctrine played out:

The enlightened ones are the ones who got cut out of the story, and the ones who we think of as the apostolic, the unbroken lineage, are actually the narrow and rigid ones. The play-by-the-rules guys who with their stranglehold on the unenlightened story, block the enlightened story for all of us…

**

Consciousness: Reincorporate the magic and mythic to temper the mental and elicit the integral (!)

More recently, Cynthia has reflected on Jean Gebser’s prophetic vision of how consciousness evolves. She suggests that our challenge is to allow our magic and mythic forms of consciousness to co-arise with our mental-rational function such that a new kind of consciousness can arise, informed by what Gebser calls ‘diaphanous awareness’; a mind more suited for our times that will allow us to ‘see through the world’.

On page thirty of her full reflection, she writes:

While the inner work of us Wisdom and contemplative/evolutionary folks may be to tend our own conscious emergence, I believe that the cultural work we must undertake together is to help REPAIR and HEAL the traditional structures we’ve inhabited so that they can become healthy vessels of the repressed mythical and magical (and for that matter, mental!) structures. My wager is that when this imbalance is corrected, the full emergence of the Integral (so clearly already waiting in the wings) will be its own unstoppable force. We don’t need to race on up to the front of the train in order to reach the station first; we have to make sure that the passengers in all the train cars are well tended and still hooked up as the station in fact rushes to meet the train.

This analogy risks being self-congratulatory and superficial, but I thought of Cynthia’s take on Gebser when considering what went right with The Realisation Festival this year. We started with a dance, there was singing, improvisation, storytelling, poetry…it was by no means all mythic and magic, but as a relatively intellectual fellow I felt my intellect was somehow ‘in its place’ in a good way - legitimate and valued but not sovereign. And because the mental, mythic and magic vibes (if not ‘structures of consciousness’) were all attended to, it felt like there were some moments of emergence and transcendence too.

***

This has been a very brisk appraisal of Cynthia Bourgeault’s extraordinary body of work, and there is a scope for a lifetime of inquiry here. There is much more to share than I can express but I wanted to take the time to explain why I find Cynthia’s vision of reality brilliant and beautiful. I notice I can orient myself within the Bourgealtian vision, that it speaks to my experience more directly than any other source.

For those familiar with Integral Theory, as a shorthand, and a signal to indicate exceptional insight, with all due caveats about the significant limitations of stage models, I would even say that Cynthia is ‘third tier’. Her work is spiritually inspired and creatively generative. Her thinking goes well beyond the mere capacity to take multiple perspectives and integrate head and heart, towards a consistently transpersonal transmission. I am not fit to judge, of course, but the only comparable theorist I know - in terms of the majesty of the visionary scope, intellectual rigour, audacity, intricacy, and vitality - is Sri Aurobindo. (As a heretic within the Christian tradition, Ivan Illich is another comparison, but I don’t find him to be quite as inspiring).

It seems to me that one of the main qualities of Cynthia’s vision is that it is expansive and varied enough to allow for a kind of ‘bothbothandandeitheror’ approach to religious affiliation. By that I mean we move from either/or: ‘Christian or not Christian?’ To both/and: ‘Both Christian and not Christian’ and it doesn’t stop there. From a ‘both both/and and either/or’ vantage point one can decide, for principled, pragmatic or personal reasons, whether to consider oneself Christian or not.

I can see why that elision could feel slippery to true believers. But I am not alone in feeling that the more expansive and non-exclusive view is the sine qua non of spiritual homecoming and the only kind of Christianity I can see all of myself in. I am grateful to Cynthia for helping me to hold such a view wholeheartedly, and the journey is not yet over…

I am also appreciative of Cynthia’s work. She is a great communicator for our age. It’s uplifting for me to see how she can pass old esoteric knowledge and vivify it with mercurial lightness and eloquence. But I would like to emphasise that to my sensibility what makes her views truly significant and compelling is a solid background of spiritual praxis. It is not a coincidence that she has been profoundly influenced by Christian monastic tradition. In other words, her outward communication rests on a very rich and cultivated inner soil, that allows one to be in touch - directly - with the inexhaustible, ever rejuvenating source.

Moving to a wider, collective level, I too am fond of Chesterton’ quote “Christianity isn’t a failure; it just hasn't started yet”. Underneath a witty formulation there is plenty of material for contemplation.

It reminds me of a key moment of inflection I experienced as a young person when I first opened myself to Christian teachings. Until that point, I had been raised to be consistently dismissive and suspicious of religions—especially Christianity. I found myself considering that the message of Jesus had likely faced the most distortion, vilification, and undermining of all major spiritual traditions. And I remember a thought coming to me: “And isn’t that… interesting?”

That was the beginning of my journey, which also feels far from over.

Cynthia has been an important teacher for me for a long time. Having attended several of her retreats and teaching events, I assure you she is indeed ‘the real deal’ - one who teaches from her own direct knowledge. I appreciate your characterization of her work as being rooted within the Christian mystical path but not constrained by rigid beliefs. I am a Christian, but I couldn’t be if I had to understand it as the only path. It’s a language, with dialects, trying to describe reality.