Primary Schools are the Cradles of Civilisation

On admiring the work of an outgoing headteacher.

Primary schools are the cradles of civilisation. It is here that we come to believe in our reliable world that is full of surprises. It is here we learn what is expected of us, and what to expect from others. It is here that we are praised for how we sit on the carpet when a story is read to us, and tacitly absorb all that that means: respect, composure, the presence of others, and the joy of concentration. It is here we learn how to get back up when we fall down and discover that it’s ok to cry, and to stop crying.

Teachers ask us to do things with our hands, legs, eyes, ears, and voices, and we notice on a daily basis that we can do things we couldn’t do before. We learn how to think well, how to speak well, how to listen well, how to play well, and through it all we learn how to learn. It’s not always easy, and we’re not sure if that’s ok or not. My seven-year-old son Vishnu is a bit suspicious of the idea of effort, and there are Taoist sages who would agree with him. But the teachers tell us it’s good to keep trying and sooner or later we believe them.

It is in primary school that our tender egos start sprouting and we all encounter a perennial law of life: I constantly want things I cannot have. At first, this feels like a scandal, but by coming to appreciate rules, gentle discipline, and moral encouragement, we become socialised. We learn to compromise. We come to see that there is enough to go around. It is not wrong that we want both remaining pieces of our own birthday cake, but the classmate with the runny nose next to us whom we don’t necessarily like needs a piece too, and we might feel bad if we don’t give it to them, and the teacher might find out, and then we’ll definitely feel bad. And so, over time, such fairness becomes a norm, making the world kinder. And so, in the gentle hum of the classroom, we learn to pay attention to what matters. And so, over time, we may come to love the experience of attending. And meanwhile, in the drama of the playground, we learn to choose peace over war.

Primary school is also where we learn what institutional authority looks and feels like, though we won’t know it by that name. The best primary schools, like the one I know - Brandlehow School in Putney, London - are suffused with a spirit of moral equality: everyone matters equally. And yet, not every kind of equality matters equally all the time. When it comes to running a school, there is an inequality of authority, and it is no bad thing that someone is in charge. Not when that person loves you. Not when that person is giving the best years of their life so that you can make the most of yours.

Last night I asked my charmingly taciturn son, Kailash, now 14, if he had any memories from his time at Brandlehow about his headteacher, Ms. Loughnan, who sadly leaves the school this week. Perhaps he remembers a story I might share to help mark her leaving the school? “No”, he said, and then paused. “She was nice though.”

I was reminded of the poet Maya Angelou’s celebrated line: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said and people will forget what you did, but they will never forget how you made them feel.”

Ms. Loughnan’s departure is a local story and came as a surprise, but in terms of the news cycle it followed the resignations of Jacinda Ardern and Nicola Sturgeon and appeared to be a similar pattern of popular female leaders who sensed their time in the role was up before others did. The contexts are different of course, though all of them had the unenviable task of leading through the pandemic. Yet having the wisdom to know when enough is enough is impressive. They all left after anticipating there was a matter of months remaining in which they could continue to give the job everything they had, rather than grind on beyond the point it was healthy for them, or good for the work they served. At a personal level, I find this kind of resolve validating because the thing I am most proud of in my chess career is finding the courage to let it go, but I can’t help but wonder if we could do better. Does it really have to be all or nothing? Couldn’t we have more sabbaticals or something?

In my last post, I spoke of discomforting political admiration, but this reflection is a more straightforward case of admiration. I know what Kailash means when he says Ms. Loughnan is nice but what I want to convey here is that through knowing Ellie (it feels a bit strange to call her Ms. Loughnan in this context) I gained some sense of what a primary school headteacher does from a lateral vantage point outside of professional education, and ‘nice’ alone will not cut it. A primary headteacher needs highly developed intellectual, social, emotional, and leadership qualities, and much more so than I think people outside of education realise. Being the headteacher of a primary school is a multifaceted and exacting job that calls for extraordinary human beings.

I don’t say that just because my mother, Lesley Owens, was a primary school head teacher back in the day. I am very proud of her career, and she went on to be an advisor to headteachers, or as we called it in Aberdeen ‘A heedie’s heedie’. But I never really knew what she did at the time, because I was too young to get into the details, and the details are where the acumen is revealed (though I do remember the pressure she was under). Most of what I know about being a primary headteacher comes from observing Ellie Loughnan over the last decade as part of the Brandlehow school community.

Kailash started reception class in 2013 when Ellie was still deputy head. On one of our first days at school, my wife Siva and I joked that you could tell who the senior teachers were in the playground at a glance, because both Ms. Loughnan and Ms. Grove - then head teacher - were wearing power boots, with commensurate but dignified swagger. When Ms. Grove resigned, a few of the parents made a point of encouraging Ms. Loughnan to apply for her post. She was more than ready and would have done so anyway, but I remember that it meant something to her that we said so. Ellie has this quality of leaving you in no doubt that she has heard you say something. A year or so later we ran the school chess club together, which we’ve done most years since then. Over the years we have of course spoken about Kailash and Vishnu, who is currently at the end of year two. But most of what I learned about ‘the job’ came from my time as an elected parent Governor in 2016/2017.

The main value of that voluntary experience was having a behind-the-scenes look at the enormity of what a headteacher contends with. They are by no means alone, and it is always a team effort, but the team looks to the headteacher to decide what to do and they are obliged to decide even (and especially) when it is not clear what should be done. After a while, it becomes clear that the school is not just a building where a curriculum is being delivered, but an ecosystem of a thousand relationships; relationships between people, within people, and in the struggle between people and policies and procedures. Not to mention all kinds of situations, which arise every day. You are called to decide, and your decisions are scrutinised inside and outside of the school.

Headteachers can be fun, and it may even be their duty to be fun, to bring joy to their colleagues and pupils, as Ellie has done many times, not least with her choreography. Ultimately, however, a headteacher bears a solemn responsibility. Learning and happiness are touchstones, but the job is, above all, to keep young children safe. Parents and guardians entrust the school with what is most precious to them. No harm should come to the children while under the school’s care, at least not beyond the joyous struggle of growing up. That’s a heavy load to bear, and it’s not an abstract concern. It was particularly intense during Covid, but it applies to children who may want to escape from school and sometimes succeed in doing so, and it applies to children with peanut allergies placed in danger by unwitting parents of classmates.

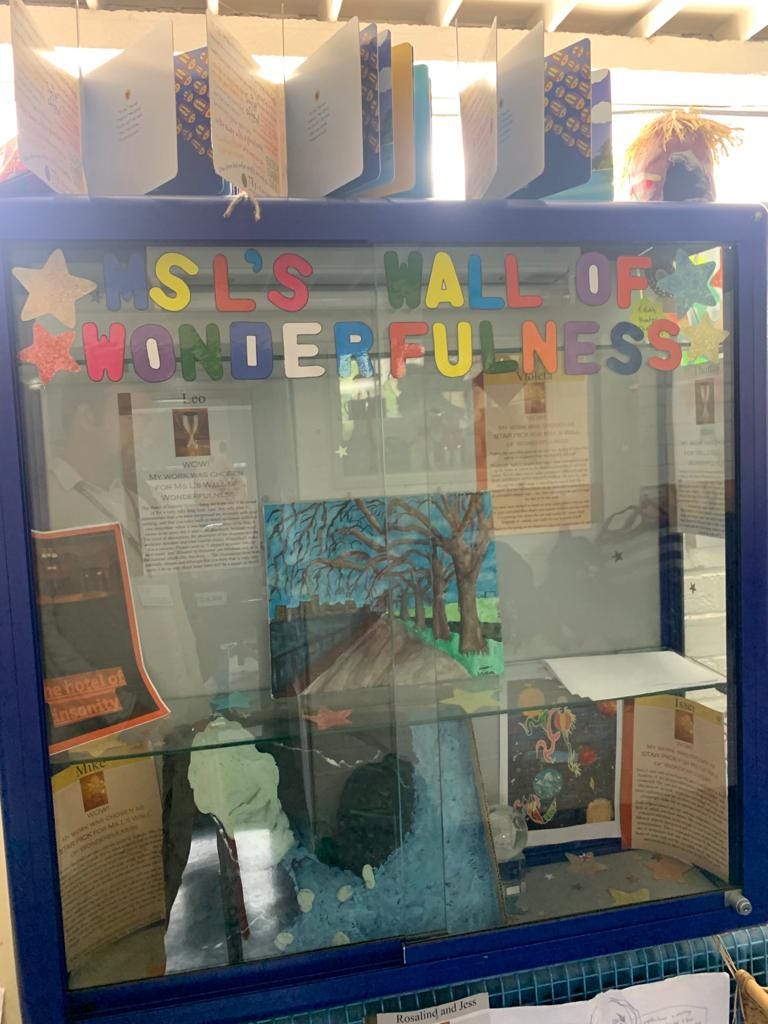

Brandlehow pupils all know about Ms. Loughnan’s Wall of Wonderfulness, the place where work of special effort and care is given due credit for the whole school to see. Pupils really want to be on that wall, and not just for the kudos, but for the experience of being really seen by the headteacher.

What most pupils don’t know, however, is that towards the end of every governance meeting, and not just then, there is usually at least one very difficult case to contend with, and often more. From among two hundred and fifty or so pupils, often there is a child who is struggling in some way, perhaps with some kind of neurodivergence, perhaps because their parents are separating, or perhaps even due to hunger or lack of sleep. A headteacher regularly has to deal with vexed and harrowing situations beyond the school that live on in the children during the day.

What struck me was not just the intensity of the responsibility but also its range. The headteacher has to deal with core matters of good teaching and child development but they have to do that while also dealing with the shifting needs of Wandsworth Council, the caprice of government legislation, leaky roofs, the constant spectre of an OFSTED inspection, periodic complaints about school lunches, worries over punctuality and attendance records, a larger than usual batch of children with special educational needs, lost property, broken equipment (I’ve noticed Ellie takes pride in fixing things), lack of space for new clubs, problems with parking, the challenge of teacher recruitment, stress-related teacher absences, interpreting school exam results and discerning why they matter and why they don’t matter, diplomatically assuaging challenging parents. And several times I have observed Ellie coaxing a crying child who hasn’t been to school for weeks across the threshold of reception. One thing after the other. On it goes. The beautiful exhausting privilege of it all.

When battling on all those fronts, it can’t be easy to return home and be available to other parts of yourself, or for others, and there is a limit to how long you can put up with that. I imagine sleep is not easy with all those issues and all those people in your head, knowing that the next day you have to get up, show up, and make a hundred new decisions with a thousand new consequences.

Whether such things apply to Ellie I don’t know, but she appears to have an extraordinary capacity to keep the soul of her work alive. I have the impression that her resilience - formidable but not infinite - comes from never allowing the bureaucratic demands of the job to detract from the love of education and the spiritual call of teaching.

As far as I can tell, she remembers the name and context of many hundreds of parents, but every colleague, and the name and context of every child in every class; the details of their allergies, their siblings, the parents, the family story – all those things to remember; as well as remembering the unique burden of leadership - all those things learned in confidence that can’t be shared. And yet, throughout it all, the meaning and vitality of the human connections remain. Ellie appears to be no more or no less herself when she looks a parent in the eye, or says no to a colleague, than when she kneels down to give her full presence to a child.

Brandlehow is a happy, nurturing school, and most people feel that from the first moment they walk in the door. That is a credit to everyone at the school, but I believe it starts from the top. Ms Loughnan sets the tone, transmits the vibe, and models the sensibility. Through the headteacher’s leadership, a whole world is brought into being: a precious haven, a crucible of delight, a home from home, a safe place to grow, a cradle of civilisation.

Thank you for taking the time to write this, we are about to take on the serious responsibility of helping London Primary schools with branding, a necessary but sometimes seen as a begrudging task mainly because of all the things you have talked about. Your article has radically changed how we will approach these head teachers - thankyou 👍🙂🫶

This is a wonderful piece Jonathan. My wife retires as primary head teacher today and your words express exactly what it takes to be a leader of a school. Each day they have to deal with a huge range of issues and challenges and the toll can be tremendous in terms of stress and exhaustion. But the rewards are enormous in terms of job satisfaction and the opportunity to inspire children to discover their gifts across the whole spectrum of life. Let's recognise that head teachers and the teachers they lead create the foundation for a successful, happy and healthy society.