There was a moment about five years ago when millions of people were suddenly running out of breath, hospitals were besieged, and I was scared. I found myself up late at night, trying to figure out whether to send my sons to their schools that had recently reopened. There were not yet vaccines or adequate medicines available to deal with COVID-19, and as a type-one diabetic, I was in an at-risk group, strongly advised to ‘shield’ and stay at home. The chance of becoming seriously unwell was high, and the possibility of dying was not negligible. It appeared that younger children could contract the disease and take it home with them, and the idea that my sons might unwittingly become patricidal biological weapons was not a happy one.

And yet, education really matters. The children were bouncing off the walls at home, the whole family wanted them to be at school, and we didn’t know how long the situation would last. My wife Siva left the research to me, and I spent hours reading epidemiology papers and following public health experts on Twitter, trying to make a sound decision in good conscience. (A dark detail from the time - there was one research paper for every 16 Covid-related deaths). The ethics of the relationship between knowledge and action had never felt so palpable.

I sought to grasp both the hazard - the increased likelihood of getting Covid if the boys went to school, and the harm - was there really a threat to life? It seems bizarre now, but it really did feel like an existential decision. I remember thinking: this is how it feels to learn as if knowledge really matters. This is how it feels for truth to be a kind of oxygen, for my continued existence to depend on making full use of my capacity to make sense of the world.

My sons stayed home for a couple more weeks, and I wrote about the decision on Medium (before I knew about Substack). Thankfully, new knowledge soon came to light that changed the odds, or maybe I just needed to feel that I could say no, to feel I could protect what I cared for. I managed to avoid getting Covid until two years later, by which time I was already vaccinated and felt much less at risk. What I am keen to convey now is that sense of learning really mattering, and the kinds of attention and diligence it evokes. I think we need more of that today.

*

Some readers may not know that I used to play chess professionally, but I can share that it’s no accident that the explosion of the popularity of chess coincided with Covid, and not just because of The Queen’s Gambit on Netflix. Life becomes more meaningful whenever we take responsibility for something or someone, as many had to do at the time. Responsibility is purposeful – it helps answer the perennial human question: what should I do? And that question should be informed by the open secret of all of our inevitable deaths. Chess simulates the meaning of life because it is a ritual encounter with death in disguise (Checkmate comes from the Persian Shah Mat, meaning ‘The King is Dead’). As with those vulnerable in a pandemic, in chess, we experience the responsibility to stay alive one move at a time. I illustrate this idea with a twist on a Zen story, in the prelude to my book The Moves that Matter (Bloomsbury 2019).

A wayward young man sought guidance in a temple on the outskirts of his city. He was weary, tired of pretending that he knew what life was for.

The resident master looked him over. ‘What have you studied?’ he asked.

‘The only thing that ever really captivated me was chess.’

The master fetched his nearby assistant and reminded him of his vows of trust and obedience. He instructed him to fetch a chess set and a sharp sword.

He returned to the young man. ‘You will now play a game of chess with my assistant, and I will behead whoever loses. If chess is really the only thing you feel is worth mentioning, and you can’t beat someone who barely knows the rules, your life is not worth saving.’

On sitting down to play, the young man noticed he was beginning to tremble; the prospect of death bringing him to life for the first time in months. Suddenly something mattered. After a few familiar moves he rediscovered the bliss of concentration and the beauty of ideas, and his superior understanding became obvious.

On realising that he would soon deliver checkmate, he looked up at his opponent. The master’s assistant was so unlike him. On the chessboard he was floundering, but he looked disciplined, dignified, and full of the goodness of life.

The significance of the next few moves would live on in perpetuity and the young man was no longer sure what he wanted from the game. He maintained his advantage, but started to make small mistakes to keep the game going.

The master noticed this change in perspective and swept the pieces from the board. ‘No one needs to die here today!’ he said. ‘Only two things matter on life’s path: complete concentration and complete compassion. You have learned them both today.’

But the master did not fully convince. The players knew the game might have ended differently. The young man stayed a while in the temple and the opponents became lifelong friends. It is not known whether they ever played chess again.

Not every game of chess feels quite so important, but I am curious to know how it would feel to live as if every moment was precious and evanescent, knowing that our time might soon be up. This dispositional quality is not about Covid or chess but about contending with the challenges of our times.

*

To attend, and learn, and think, and decide as if our lives are on the line - how often do we do that?

Not often enough. Understanding has become fugitive. There’s too much scrolling, skimming, and scanning going on, and too many promissory notes. It is now commonplace to like reading material as an act of merely noticing it, rather than appraising it. Liking is now a reflexive digital impulse as much as an underlying sentiment. Sometimes we even email ourselves online material as if squirrelling away brain food for the winter, or take a screenshot as a kind of proof for an imaginary court case, or make a brief comment to mark our social presence as if waving from across the street. And all the while, we disavow that we are unlikely to invest further time in whatever we just signalled to ourselves and others to be so worthy of attention.

I note these tendencies not as judgment but as compassion. I am as guilty as anyone of these patterns, which are a structural feature of an information system parasitic on attention and built on the pretence of giving people what they ask for and the false promise that if we have to part from what seems to matter now, we can always be reunited in the mythical land of Later. The problem is not just that we are drowning in information, screaming for knowledge, and hoping for wisdom, but that shallow learning has become ubiquitous. Our dysfunctional infosphere is compounded rather than caused by AI large language models, which appear to militate against the need to learn deeply. We are being duped into thinking that it’s enough to get the gist, and outsource the graft, and perhaps even canny to do so.

And all of this co-arises with the growing realisation that, as Zak Stein put it, Education is the Metacrisis. Here is how I put it in the preface to that essay:

The playful and profound analysis in Education is the Metacrisis helps the reader reimagine education from a significantly more expansive perspective than they may be used to, and connects that to the psychological and spiritual crises lying behind our major societal and ecological challenges... Through Zak’s work, the very idea of education is profoundly and helpfully defamiliarized, such that the word does not refer primarily to the conventional arcana featuring classrooms and exams, but becomes the beating heart of intergenerational transmission and social autopoiesis, the fundamental matter of how society maintains, renews, and transforms itself. That emphasis is of no small importance in this historical moment, where there is so much precarious excitement, much is asked of us all, there is so much to lose, and so much is up for grabs.

The importance of learning is pancontextual and inter-contextual, and it applies not merely to the transformative civic, moral and aesthetic education of Bildung but also to the curriculum and cultures of schools all over the world. There is a quite literal sense that it is time for us all to learn as if life depended on it.

*

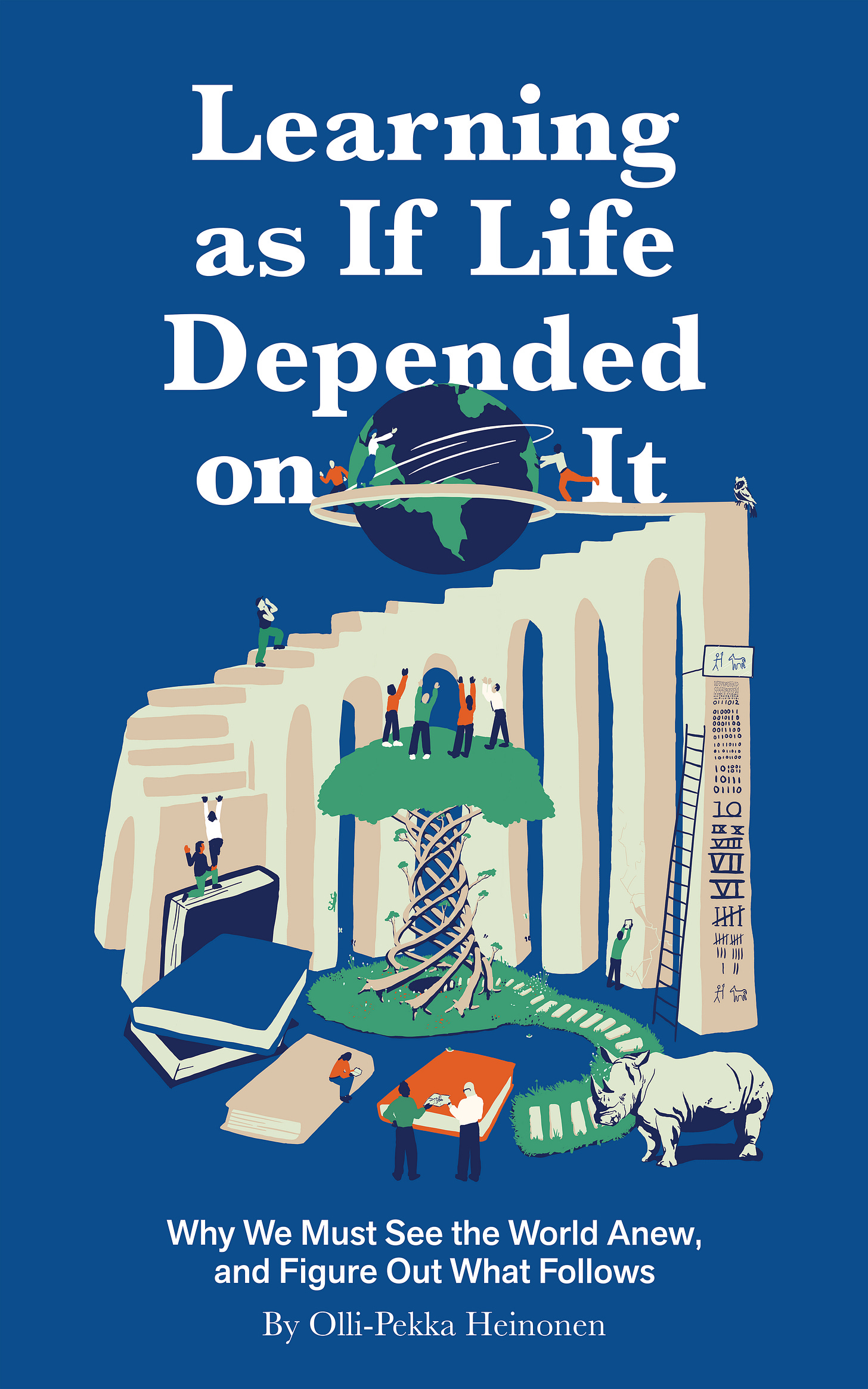

I am therefore pleased to have played a role (through my day job at Perspectiva) in bringing into being: Learning as If Life Depended on It: Why We Must See the World Anew and Figure Out What Follows, by Ollie-Pekka Heinonen. This book will be released very soon, on November 4th 2025, so please pre-order it in the UK now or in the US, or in the EU (Pre-orders really help!).

The cover design is by Christopher Burrows, but all responsibility for the rhinoceros rests with me. It is a nod both to the reality of extinction through our failure to learn and the threat of fascism through our failure to learn.

Learning as if Life Depended on it is a work of planetary reckoning by the Director General of the International Baccalaureate, Olli-Pekka Heinonen. Informed by his statesmanship and Finnish cultural heritage, Heinonen explains why the root cause of global crises is the failure to perceive the ideas we live and work with. Heinonen offers a four-part journey through our current predicament, the illusions we live by, our untapped potential, and transformative pathways. Education, he argues, must now become a collective act of reorientation.

My former PhD supervisor, Guy Claxton, endorses the book as follows:

Civilisation is under threat. Large numbers of people who are thoughtful, ethical and brave are required to protect it. Education ought to be the incubator of such people. Educationists who can see clearly what’s needed, and show schools the way back to their fundamental purpose are in short supply – but Olli-Pekka Heinonen has emerged as the leader of this small but crucial pack. In this wise, lucid and heartfelt book he offers us hope and direction, not just for the regeneration of education, but for the preservation of our planetary home.

– Professor Guy Claxton, author of The Future of Teaching and the Myths That Hold It Back.

*

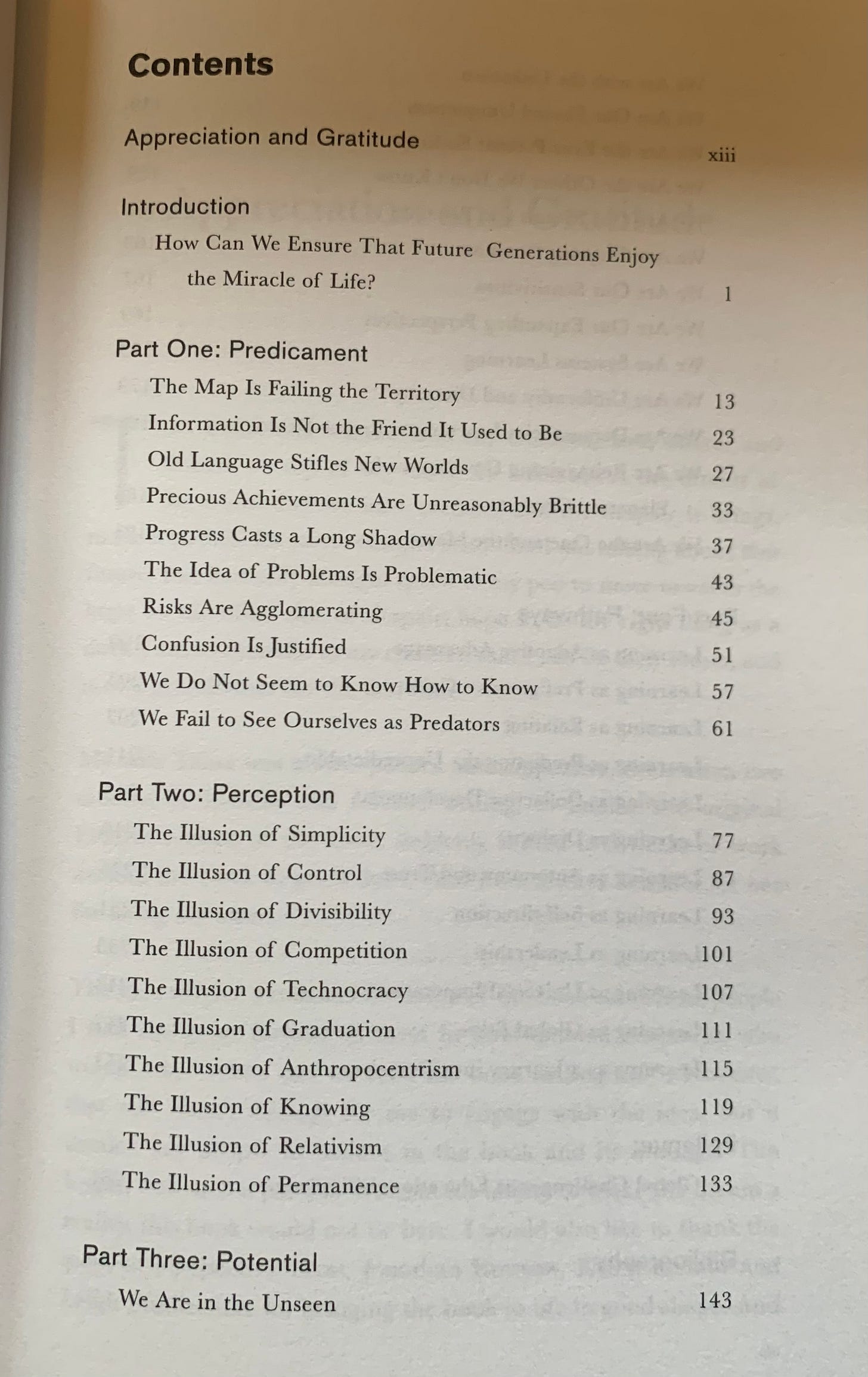

The book began as an English translation by Eva Malkki, from the original Finnish text, Eletaan Ihmisiksi - Yhteisollista viisautta etsimassa by Olli-Pekka Heinonen. That translation was adapted and edited in close collaboration with the author, to reshape the structure and expression for a new readership, as you can see in what are hopefully intriguing contents pages:

I see the book as a work of epistemic leadership - it’s about encouraging educators to wholeheartedly reckon with the state of the world and consider what follows for how we encourage each other to try to understand it well enough to protect our only viable habitat. We almost called the book Beyond Problems and Solutions because it is expansive in spirit, encouraging readers to see the world anew (and yes, ‘anew’ is a word, and a lovely one.)

There is more to say substantively, but one thing that drew me to the book was Olli-Pekka’s distinctive writing style, which is curiously Finnish, and sometimes strikingly aphoristic. I will whet your appetite for the book with a few gentle zingers:

We are like coastal flowers transplanted into the mountains.

Utopias are like meta-level answers to questions that were unanswerable in the first place.

Horseless carriages – later known as cars.

The sport of jumping to conclusions is not a healthy one to practise: the risk of jumping in the wrong direction is high.

Invulnerability is a dangerous illusion, which makes us unable to prevent the snake from slithering into Eden.

Like driving on a windy mountain road in a car with a locked steering wheel.

Fear drives groups together like herds of antelope running from a lion.

Democracy cannot be based on fear; it must stand on reciprocal trust, which is one of the hallmarks of love.

Humanity appears to have regressed into adolescence.It is not enough to be authentic, because you can be inauthentically authentic.

A game is only fun when you take it seriously.

Breaking poor routines is an act of everyday heroism.

“Being yourself” doesn’t work by yourself.

I would like to have been a fly on the wall, back when there were no flies or walls.

Tomorrow morning, when you squeeze your stripy toothpaste onto your brush, consider how it got there.

The system changes when the nature of its interactions changes.

Instead of carefully defining what each member of the organisation should do, it is more important to determine what no one should be doing.

It is a perspective shift from solving problems to developing the system.

We believe that we, as humans, protect nature. The situation is fundamentally the opposite: nature protects us.

Slowness is a quality of the brave.

So please buy Learning as If Life Depended on It, published by Perspectiva and distributed by Penguin Random House. And I am curious to hear whether you’ve had this experience of ‘learning as if life depended on it’, and if so, how it manifested.

Until next time.

Jonathan.

For those of us in the US boycotting Amazon (because Bezos has openly embraced Trump and censored the Washington Post, while Amazon maintains a warehouse injury rate twice the warehouse industry norm and fights unionization), the book is available for pre-order through local independent bookstores too, at the same price. I've done so.

It feels like Education has rarely lived up to its definition mistaking substance for process. Even in its narrow interpretation that is widespread in schools it treats knowledge as the prize rather than the skill of acquiring it.

The book sounds interesting and appears to have some resonance with the recent series of chapters published on Substack by Anarcasper the first of which is here: https://open.substack.com/pub/anarcasper/p/the-learning-grove?r=2rwmeb&utm_medium=ios

Life is absolutely dependent on learning and it is a miracle of the human spirit that many are able to transcend their school experience and find their own path to enlightenment.