Flirting with Modernity(2)

Are we really in a time between worlds?

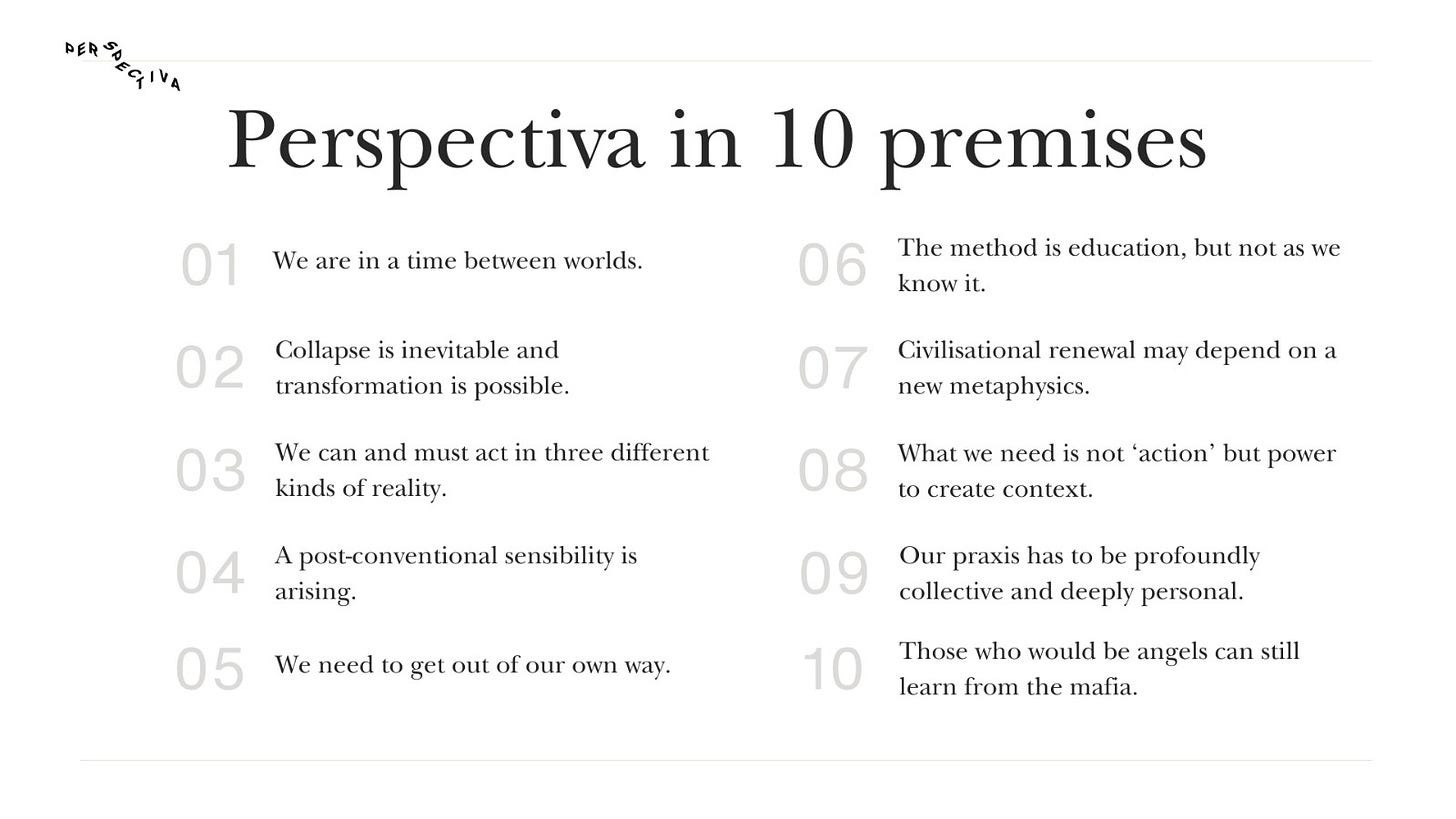

The first of Perspectiva’s ten premises is that we are in a time between worlds, which is our way of acknowledging the importance of history and the value of giving some shape and specificity to the character of this historical moment.

The expression ‘a time between worlds’ originated in Zak Stein’s excellent book Education in a Time Between Worlds, published in 2019. The claim is empirically grounded and theoretically elaborated in the first chapter, especially informed by models from metahistorical analysis (eg Peter Turchin) and world systems dynamics (eg Immanuel Wallerstein). In other words, it’s not just an elegant turn of phrase.

A little later, Zak further developed his ‘time between worlds’ idea in his Perspectiva essay on Comenius (see pages 18-21, especially), which includes an image (below).

We also spoke about this together in early 2022.

Despite the depth, acuity and richness of this analysis, recently I have noticed I lack conviction when I say ‘we are in a time between worlds’ and I’m trying to understand why. My qualm is not about any particular detail of Zak’s analysis but the experience of incredulity, discomfort, and perhaps even vainglory I feel when I speak of “a time between worlds”.

To function with a time between worlds as a premise is a kind of ‘conceptual practice’. This is a helpful idea of Matthieu Queloz from his book The Practical Origin of Ideas, where he defines it as follows:

A community’s practice of letting its thoughts, attitudes, and actions be shaped and guided by a given idea. Unlike mere practices, such as walking on one’s feet rather than one’s hands, conceptual practices are essentially shaped by sensitivity to conceptual norms or reasons—take away the idea in terms of which those norms and reasons are articulated, and the practice collapses.

My aim here is not to “take away the idea in terms of which those norms and reasons are articulated”, but to question what is implicit in the claim and what I touched on in the prior post, namely, that modernity is ending.

‘Time between worlds’ has been an important part of my conceptual practice because it helps to clarify the big-picture context of the work of my day job at Perspectiva and provides the historical (and historiographical) context for other aspects of our work, including the philosophical coherence of metacrisis (all the premises, but perhaps especially premise 2) and to a lesser extent the cultural relevance of metamodernism (likewise, but especially premise 4).

However, if “our thoughts, attitudes, and actions” are to be guided by this idea, it’s important to feel and embody it.

At a more vernacular level, “we are in a time between worlds” is often uttered descriptively, as an assumed matter of fact, or a statement of tribal belonging. I have noticed “this is a time between worlds” can also sound like a coercive framing, as if those who see clearly must acquiese to modernity to ending, and want it to end, and help it to end, until before we know it we are kicking modernity out the door and on to the street, as if taking control in a house party that got a bit wild.

“Sorry mate, but this is a time between worlds. Come back when it’s sorted, yeah?”

*

The time between worlds idea matters because it implies everyone’s work is part of an even bigger process beyond anyone’s direct control. Whether you are working on climate, biodiversity, law, democracy, education, health, technology, finance, philanthropy, or journalism, your context should be informed not only by a what and a how and a why and a where and a who, but also by a when, and perhaps especially by when. You are a historical actor, living and working in time, and this historical moment is qualitatively distinct. It asks something of you. But what?..

There is an aesthetic dimension to the qualms, too. Ideas often have half-lives, and they can gradually become depotentiated from overuse. A few years ago, particularly during the pandemic, ‘in a time between worlds’ felt charming and elucidating, but now it feels overfamiliar, too easy to say, and less beguiling. It is tempting to tack on ‘a time between worlds’ as a conceptual modifier to confer gravitas to almost anything. There is comic potential here, for instance: “Eating bananas in a time between worlds” or “Washing your hair in a time between worlds”. Last year, Perspectiva issued a funding application for a series of new books with the working title of ‘Thinking in a Time Between Worlds’, and Layman Pascal called his cheeringly eccentric new book: Gurdjieff for a Time-Between-Worlds. We are all at it!

We should not conflate aesthetic reactions to the use of terminology with the intellectual coherence of the underlying idea. ‘A time between worlds’ is, or at least was, an elegant way to express a more general pattern of claims about betweenness that stem from a wider range of sources, disciplines and traditions in anthropology (‘liminal’) and sociology (‘interregnum) and meta-history or historiography, as I outlined in a prior post about being between worlds in 2021 here.

However, framing language matters a lot, for reasons I outlined in prefixing the world and my Perspectiva colleague, Ivo Mensch, who is working on innovations in spiritual practice feels the ‘time between worlds’ premise is a descriptive ontology that keeps us trapped in revelling in the in-between rather than a generative ontology that might move us out of it. I describe that distinction as follows in my third post on threeness:

Descriptive ontologies focus on cataloguing, classifying, and analyzing existing entities and relationships. Generative ontologies seek to produce new realities. Both are required, and the former can even be a kind of training for the latter.

A descriptive ontology says: this is how things are, we can see the world through it.

A generative ontology says (or rather enacts, enables, instantiates…): In light of how the world presents itself to us at the moment, here is how we can think of things, here, now, and for the purposes at hand (informed in some cases by years of metabolising descriptive ontologies). Generative ontologies are closely related to moral imagination which I have described before as perhaps being a sine qua non for the peaceful resolution of conflict. We have to allow ourselves to see anew.

There is some danger of fatalism in a descriptive ontology that signifies a holding pattern rather than a generative ontology that forges a direction (though to be fair, they are not mutually exclusive).

In recent months, I have also noticed some people don’t like how the expression displaces you from the world we are in, as if to say, contra James Bond, the world is indeed enough.

Regardless of the objective basis of the between-worlds claim, some find the idea of being ‘in-between’ inherently discomforting, perhaps optional, or even gratuitous, and they prefer not to start from there: “I am not between anything. I am here! Now! Let’s go!”. When I was in Mexico City in 2019, I came across the term Nepantla, which is also about betweenness. I asked our thoughtful tour guide and translator if Nepantla could ever be experienced as a good thing. It’s a small straw poll of one person, but for him, the valence of the idea was distinctly negative, and I remember that surprised and disappointed me - I was over-invested in the charm of being ‘in-between’. And yet, if I consider that sometimes I get to ‘time between worlds’ by saying we have entered a new phase of geological time caused by human overreach, with an entirely new information system run on a new kind of ‘intelligence’ that dehumanises us, and an economic model based on a frontier logic that is running out of frontiers - it’s clearly not a positive appraisal.

Others don’t like the framing because they hear a pre-tragic, ‘all shall be well in the end’ wishful thinking, as if the collapse and violence and delusion that permeate the news are some kind of legitimate precursor or the birth pangs of a better world. If you are wedded to a beneficient evolution of consciousness, that might mean we are, in a sense, waiting for God, but it risks being more tragicomic, like Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. I jest, but something like this:

“Let's go."

"We can't."

"Why not?"

"We're waiting for Godot, in a time between worlds…”

**

The historiographical time between worlds claim, the philosophical idea of metacrisis, and the cultural theory and practice of metamodernism all co-arise and mutually inform each other. In 2021, Perspective Press published a book compilation called Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds to flesh out these ideas with multiple stars of the liminal web writing across disciplines and genres.

That book was one of the many casualties of the pandemic and has been somewhat neglected, but the material is high quality and still pertinent (and on sale!). We still plan to make that book the first of several such Dispatches. As part of introducing the series, I try to clarify the ‘time between worlds’ claim as follows:

The premise of this series is that the myriad forces that shape global history are now burgeoning to such an extent that our conventional patterns of collective understanding, sentiment and expectation are failing to make sense of how we should act. Sometimes it feels like even the best we can do won’t be good enough to save ourselves from ourselves. For instance human rights and international law often look insipid in the context of transnational financial power, the political spectrum seems otiose when policy proposals are subsumed by culture wars, and metrics like IQ and GDP seem increasingly quaint because they are ostensibly solid empirical ground, but when we inspect them for their fidelity to the world as we find it, they lack a sound metatheoretical basis, appear to lie on conceptual quicksand, and fail to guide discerning action.

While we are struggling to make sense of the world we have known, an experience of ambient potentiality is arising within and between people too. This metamodern feeling is shaped by our global digital context and ecological reckoning but also cosmological reenchantment, in which our shared insight into the precarity of planetary life and its elusive meaning heightens our sense of intimacy and elicits new impulses of wonder and tenderness. These sentiments are also manifesting in intellectual and creative output, and in design and policy processes that seemed far-fetched until recently, but are clearly emerging; for instance bioregionalism, universal basic income, land reform, post-growth economics, wiser crypto currencies, and the transformative civic education known as Bildung.

These new patterns of living have not yet matured or coalesced, and may not, because they lack political capital and they have not been properly tested by time, so the better world that might arise is merely intuited, glimpsed, and not quite tangible. Yet we cannot but hope that something is arising that will speak to our pervasive sense of intellectual disorientation and aesthetic longing. That sense of discomforting betweenness is sufficiently strong that the attempt to wholeheartedly consider the nature of ‘truth’ and ‘we’ and ‘time’ that define our experience is not of mere philosophical interest but part of saving civilisation from itself. These philosophical considerations may appear niche, but they are about our place in the evolution of consciousness and history’s great cosmic unfolding, detailed by visionaries like Teilhard de Chardin and Sri Aurobindo and reappraised in recent scholarship on Owen Barfield and Jean Gebser.[i]

The notion of ‘worlds’ is about the evolution of (inter)subjective and (inter)objective aspects of our shared reality, while the idea of being between worlds is meta-historical and historiographical, concerned with how the meaning and pattern of events and processes of history might best be organised through the designation of epochs, periods and phases of transition. The subjective(psychology) and inter-subjective(culture) aspect of being in ‘worlds’ stems from social theories about patterns of common understanding, meaning and expectation sometimes called our social imaginary, which Charles Taylor describes as “a wider grasp of our whole predicament...not a set of ideas; rather it is what enables through making sense of, the practices of society.”[ii]

And yet our imaginary arises through the objective (material) and inter-objective (institutional) features of reality. These features of ‘worlds’ are disclosed not by human experience as such, but by data, though it is only through theoretical concepts derived from our imaginary that we can turn data into information, and thereby decipher trends about underlying dynamics in demographics, economics and politics.

Please note that the contention is not that we are merely in a time between stories, systems, or paradigms, but that ‘the world’ as we have known it and as it is manifest - inside and out, individual and collective - is ending.

But is ‘ending’ quite right? I am reminded of the saying that what a caterpillar sees as the end of the world, a wise person sees as a butterfly. Bonnitta Roy builds on this metaphor to say we often forget that the caterpillar has to die to allow for the transformation to happen. Some feel this inexorable ending more than others, and it’s possible to feel it in many different ways, as loss, as anxiety, as discombobulation, as hope, as urgency, as challenge. But I think it’s noteworthy that many millions of people do not feel it at all.

The use of ‘worlds’ rather than paradigms, systems, or stories is important because it encompasses all aspects of reality – subjective, objective, inter-subjective and inter-objective. I flesh out this idea with ‘five flavours of betweenness’ where I ask whether the best way to understand the ‘time between worlds’ claim is cultural, systemic, paradigmatic, ontological, metaphysical, or all of these.

Given that full range of meaning is potentially ending (in some sense), the scale and scope of change in question are epochal. And now we get to the point that ‘modernity’ is perhaps the only conceptual object with sufficient depth, familiarity and capacity to capture the fullness of the claim. The simplest way to understand ‘time between worlds’ is to suppose that the world of modernity is on the way out, and some other ‘world’ or historical epoch (maybe better, maybe worse, but definitely different) is on the way in.

But that’s not simple at all! A world cannot be traded in like you might trade in an old car for a shiny new one, nor will any such change be universally accepted. The idea implies many decades of struggle on multiple fronts, probably wars, and it implicates a world-historical process lasting several decades, and a lived experience of indefinite betweenness.

This is why, if we hold ‘time between worlds’ as axiomatic, we need to make better sense of what it would mean for modernity to end. And if we don’t or can’t understand the ‘time between worlds’ premise as ‘modernity is ending and we-know-not-what-is- arising’, we must work a little harder to justify the premise, or let it go as part of our conceptual practice.

Next in this series I plan to consider Anthony Giddens’s conception of modernity as being “a juggernaut” and what follows for it being unable to stop, to look at Jason Ananda Josephson Storm’s contention that modernity is a myth, and to consider Vanessa Andreotti’s ideas that our challenge is to learn how to hospice and/or to outgrow modernity.

It might seem like a lot of theoretical work, but practice is informed by theory, and I remain drawn to it. I see it as part of my job to understand what our big picture historical context is, and communicate what it means for civil society actors, businesses and governments trying to do good work in the world; a world that can seem like it is falling apart, but may not be.

Let’s see where we get to. For now, I’ll play you out with the R.E.M. classic:

It’s the end of the world as we know it, and I feel fine.

I resonate with what you wrote about here. I have been eager to find others who want to discuss, rather abstractly, what a new order could look like (because I think that's what's needed). Much of this "in between" that you wrote about (and seemed somewhat unsure of how to define it in words) is merely what I see as "transition." We are in a transitional phase, one in which old models are no longer serving us and are now collapsing. I have plans to write about this in my blog soon. A big aspect of this collapse is that we need new types of leaders when we rebuild, which would result in a new type of leadership model. We can't just use old models because they are no longer appropriate for our modern society--plus, they are being destroyed too completely, making it too difficult if not impossible to change things back to how they were if Trump disappears.

In terms of new leadership and creation of a new structure, I sense that females, artists and introverts will play a big role here. But most people don't think this far ahead about society, nor do they sense these changes on an intuitive level. That is why I'm excited to read your post. Please let me know if you are part of any blog or groups that focus on what you wrote in your post.

Thank you, Jonathan, for this textured musing. I find myself both resonating with and troubled by the phrase “a time between worlds”—not because I doubt the analysis behind it (as you rightly note, Zak Stein’s grounding is robust), but because of the subtle grandiosity the phrase can carry when spoken aloud, especially in public or strategic contexts.

There’s something about it that feels a bit too… cinematic. As if modernity is already halfway buried and we’re all standing around waiting for the new protagonist to emerge. But perhaps modernity isn’t ending—it’s composting. And composting isn’t linear, nor is it photogenic. It’s slow, messy, and full of rot and life at the same time.

This is where I’ve found Vanessa Machado de Oliveira’s work—Hospicing Modernity and Outgrowing Modernity—especially useful. She doesn’t frame this moment as a clean exit from one paradigm into another, but as a deeply relational and metabolic process: one of sitting with grief, with complicity, and with what she calls “the dis-ease of separability.” Modernity may not be ending like a novel; it may be dying like a body, and we are midwifing and mourning it at the same time.

So rather than asking whether we’re between worlds, I’ve been wondering:

• What are we metabolizing, and what’s metabolizing us?

• What rhythms are ending in us, whether or not modernity ends around us?

• What does it mean to stay with the compost heap, rather than escape into transcendence?

I’m deeply grateful that you’re asking these questions in public. They need tending, not just answering.