Imagining a World Beyond Consumerism

Five forgotten essays written by the sea in Cornwall in March 2017

Dear Readers,

I hope this finds you well, or at least finds you. I’m busy preparing a ten-week online/offline hybrid introductory course on the metacrisis. I am also working to vivify a dormant media project, preparing Perspectiva’s next batch of books, and keeping the show on the road at home. I have several drafts I am eager to get back to here - especially the one about the women who made me cry - but I don’t think I can write creatively here until next week at the earliest.

However, I do have something that I am excited to share.

I just remembered that back in the day, I wrote a series of posts on Medium about getting beyond consumerism. I am glad to rehome them here on Substack in one place. All is new that is well-forgotten, and these posts are so old now that they feel new, if that makes sense.

While early conversations about Perspectiva began in the summer of 2015, the charity I co-founded and now lead was not established until late 2016. These posts formed the thinking behind our first successful funding application to the JRCT, which - to their credit- still has a ‘beyond consumerism’ strand of inquiry - I wish more funders invited that kind of transformative thinking.

I wrote all five posts in a small studio flat in St Ives, Cornwall, in March 2017, where I was on a week-long writing retreat. I remember I had other writing plans, but these posts just popped out, one after the other, as if the muse needed to give birth to quintuplets. I believe March 2017 was the last time I managed to set parenting aside for more than a day or two. I remember the view of the ocean from a first-floor window and periodically going out for a walk in the elements - mostly rain and wind at the time. I felt enlivened by the sound of the waves crashing against the rocks and the sensation of salty moisture in my hair and skin. I also remember being eager to get back to the desk and that sequence of opening the door, hanging up my wet jacket, closing the door, taking my shoes off, and walking from the hallway to the main room to perch myself back on the chair to look out over the ocean again.

**

Five posts together make this a monster post! You may require more than one session to get through it. I have written sub-heading titles and it makes sense to read them one at a time, but if you want to binge-read, that’s ok too. Netflix can wait. I edited them very lightly, but there are some typos and inconsistencies and they are all more or less as they were over seven years ago.

I begin by detailing the emotional logic of consumerism, then consider what a post-extrinsic society might look like and how we might move towards it. I then consider human limitations and how we might overcome them, and try to answer the perennial question of what we should do. The final part is a little addendum reflecting on the connection between a policy emphasis on well-being and the role of human maturation and education in forms of well-being that are not merely hedonic, but also tied to learning and purpose.

I am slightly embarrassed by the posts now! There is some naivety here, too much explicit emphasis on ‘human growth’, and no real anticipation of technological change. I have mixed feelings about human development as a societal aspiration, and am wary of ‘the growth to goodness fallacy’, as I recently indicated in The Inner Development Goals on Trial. However, I am also very proud of my younger self’s attempt to have the audacity to think about what it might mean to get ‘beyond consumerism’, and there is a lot of rich material below that I am glad to see again, and share with a fresh audience.

Over the years these ideas were revised and they matured into essays including Bildung in the 21st Century(2019), An Open Letter to the Human Rights Movement(2021), and latterly to The Flip, The Formation and The Fun (2023) and Deactivating the H2minus Vortex (2024).

It’s good to go back though, sometimes, to our younger selves trying to figure it all out.

The Logic of Consumerism (March 14, 2017)

I am responding to a brief about how we might go ‘beyond consumerism’, which is much harder than it sounds. Consumerism is deeply problematic, but despite its obvious limitations, harms and absurdities, it is remarkably difficult to displace as our default societal setting and plot.

Consumerism is not consumption, which is a basic human activity that predates capitalism. Hunter-gatherers, for instance, consumed the products of land and used animals for various ends. Consumerism is not capitalism either which is a slippery notion that takes many forms, but it is a key aspect of the most common modern expression of it.

Consumerism is simply our prevailing cultural and economic modus operandi. It is what we do, to some extent who we are, and it is ideological in nature because it defines our sense of normality. Perhaps consumerism is what capitalism does to consumption — it turns a simple human activity into something culturally hegemonic.

The familiar critiques of consumerism include its deleterious ecological impact, its failure to offer enduring satisfaction and the comical absurdity of ‘spending money you don’t have to buy things you don’t want to impress people you don’t like.’ So consumerism is unsustainable, unrewarding and ultimately absurd. Yet it endures, and it’s hard to imagine replacing it.

Why?

Consumerism is fundamentally more logical than it might at first appear. I started thinking about this after connecting two references that use ‘logic’ in untypical ways. Tim Jackson writes about ‘the social logic of consumption’ in Prosperity without Growth (2nd edition, 2017) and Martijn Konings has published a (brilliant but inaccessible) book called The Emotional Logic of Capitalism (2015).

Konings is particularly noteworthy because he believes progressives of all stripes fail to grasp that money is more like an icon than an idol, in other words it is not something people worship in itself (‘Money is God’) but rather something that represents forms of life that people identify with (‘Money is me’).

“Progressivism, in short, overlooks the immense social and psychic power of capitalism to be affectively persuasive”. This line comes from a good review of the book by Bryant William Sculos who adds: “Put simply, capitalism and its subjects are co-constitutive of everyday life, and therefore any comprehensive analysis or critique of capitalism, must take the emotional and meaning-producing aspects as central defining characteristics of contemporary capitalism. This is “what progressives have missed.”

Forget about ‘progressives’ for a second, and remember that consumerism as usual is just not an option full stop. If nothing else, consumerism drives our use of fossil fuels, which are the preeminent cause of climate change, a pre-competitive issue for everyone: no viable planet, no competition.

So what to do?

The first part of the answer is about the ideological context for modern consumerism, neoliberalism (‘The state led remaking of society on the model of the market’ — Will Davies). It has become hard to be intentional about the future — to imagine and shape the worlds we want to live in — because the modern state rarely assumes any role in doing that or in encouraging us to do it either. I wrote about this challenge last week in my new capacity as a CUSP Fellow — here. That’s not about going beyond consumerism as such, but it is an important part of the context, and helps explain why the right level of analysis for consumerism is probably the level of the social imaginary.

‘Imaginary’ is not a term widely used in public debate, but it has been developed by the Canadian Philosopher Charles Taylor and the Greek-French social critic Cornelius Castoriadis amongst others. I think it’s an increasingly necessary conceptual tool to make intellectual sense of what is going on in the world. Perspectiva’s researcher Sam Earle gives a good overview of what it means, with a simple definition of an imaginary being: “the encompassing paradigm of ideas, beliefs and practices that makes society possible.”

The imaginary is not ‘the system’, it’s not ‘the culture’, it’s not ‘the ideology’ — it is our experience of navigating all of these things in search of a sense of acceptable behaviour and desirable forms of life. We are stuck in a consumerist imaginary and it is very hard to see a way out of it because we see through it. Imaginary is related to imagination in some very specific senses, and this is one of them — our imaginaries constrain our imaginations because they circumscribe our felt sense of what is knowable, viable and doable. As Pablo Picasso once put it: “Everything you can imagine is real.” To which I would add: but only everything you can imagine.

The relationship between imaginaries and logics has not been developed to my knowledge, but here is one way to look at it. People, communities, organisations and governments do things for reasons that make sense relative to their imaginary, but not otherwise. The background setting that shapes implicit operational logics and narrative parameters. The imaginary determines when explanations need to be given, and when they don’t. This helps make sense of why growth is endlessly discussed, with all its adjectives (inclusive, green, strong, low) but the need and desire for growth as such is rarely considered ‘on the table’ in public discussions. It is not so much a policy idea to be debated as the idea that determines which policies are to be debated — that’s why the notion of imaginary is helpful — it reveals what we are subject to, and what we can ‘take as object’ and relate to through discussion.

What then are the implicit logics of consumerism, and what would it take to get beyond them?

The emotional logic of consumerism is about meeting human emotional needs. A detailed account of emotional needs is outlined in the impressively well evidenced and interdisciplinary ‘Human Givens’ approach whereby it is argued that we all need security, autonomy and control, status, privacy, attention, connection, intimacy, competence and achievement, meaning and purpose.

The important thing to grasp here is that such emotional needs do not seem to be ‘socially constructed’ — they are a function of being a human animal and appear to be universal. The basic proposition is that all emotional distress and mental illness are caused by a failure to get innate needs, particularly emotional needs, met in balance.

And here is the thing that is hard to accept for many. Consumerism, for all its faults, does meet all of the above emotional needs, at least to some extent, and the other logics of consumerism are in some ways derived from this basic achievement. It follows that the key to going ‘beyond consumerism’ is to understand these emotional needs better and fulfil them in different ways.

The social logic of consumerism is about meeting the need to create, maintain and experiment with identity (status, attention, connection, meaning) and there is a role for conspicuous consumption in that process in that at an experiential level, at least momentarily, ‘you are what you buy’. The key psychological process here is cathexis which describes a process of attachment that leads us to identify material possessions as part of our selves — those things — homes, cars, clothes, teddy bears that we consider ‘part of us’. (Attachment to rupas in Buddhism fulfils a similar function.)

The economic logic of consumerism is about meeting the need to maintain the cycle of investment and return through growth that keeps the economy functioning — that’s what keeps us in ‘jobs’ and our livelihoods intact(security, autonomy and control, meaning and purpose). However, Tim Jackson pertinently asks (ibid p117): “Is the system still serving us, or is rather that we are now serving the system?”

The technological logic of consumerism is that it meets a need for novelty which stems from other needs, for instance competence and achievement in relation to a new phone, or meaning and purpose through a new car.

The legal logic of consumerism is that it meets a need for ownership (privacy, status, control) not only directly, but by creating markets for products stemming from ideas that can be owned through intellectual property protection.

The political logic of consumerism is a little harder to fathom. It meets a need for better futures (security, purpose, control) such that politicians can make promises on which to get elected, for instance by improving purchasing power through tax breaks, or job creation.

The spiritual logic of consumerism is a deeper question, and Tim Jackson seems to argue that it is about allaying anxiety by ‘filling the empty self’. In 1955, economist Victor Lebow stated the point more broadly:

“Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction and our ego satisfaction in consumption. We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced and discarded at an ever-increasing rate.”

The mention of rituals is noteworthy, but I wonder if a deeper way to state the point is that consumerism meets the spiritual need not to think about death, through endless ritualistic distraction. A much wider discussion of spiritual need is detailed in my 2014 report, Spiritualise.

Jackson sums up why consumerism is so ‘sticky’ as follows(Ibid p116):

“The empty self is a product of powerful social forces and the specific institutions of modern society. Individuals are at the mercy of social comparison. Institutions are given over to the pursuit of consumerism. The economy is dependent on consumption for its very survival….Perhaps the most telling point of all is the rather too perfect fit between the continual consumption of novelty by households and the continuous production of novelty in firms. The restless desire of ‘the empty self’ is the perfect complement for the restless innovation of the entrepreneur. The production of novelty through creative destruction drives (and is driven by) the appetite for novelty in consumers.”

If consumerism meets emotional needs, and if those emotional needs manifest through a variety of logics, and if those logics derive their validity from our prevailing imaginary, what follows for how we go ‘beyond consumerism’?

In essence, we need to disembed ourselves from the prevailing consumerist imaginary and introduce competing logics that meet our emotional needs in different ways.

How we might do that will be the subject of my next post.

Towards a Post-Extrinsic Society (March 19, 2017)

I ended part one with a rhetorical question and a promissory note about how we might wake up, and go ‘beyond consumerism’.

The first thing to say is that we are already beyond consumerism, but in a diffuse, localised and mostly private way. Anthropologist David Graeber argues that even communism is embedded all over the place if you know where to look for it. For instance the Marxist principle ‘from each according to their ability to each according to their need’ is what happens in families every day — most of my work as a father is communist in that respect.

Gerry Cohen’s famous essay ‘Why not Socialism?’ pushes the point further with his claim that there is no principled reason why ‘camping trip values’ - in which everybody naturally chips in for the common good - should not be the values that we adhere to across contexts. More generally we know what it’s like to value something or somebody as ends in themselves, we know how it feels to create something beautiful, to experience wonder, be touched by admiration, or learn for the love of it. We know how it feels to be at ease, and not have an itch to buy something. We are clearly beyond consumerism in so many ways.

The challenge is that the sources of value and practise that lie beyond consumerism are not politically enfranchised. There are several levels to the challenge, including macroeconomic, political, cultural, technological, social, psychological and spiritual. We need to be able to separate these levels in theory in a way that remembers they are joined together in practice.

The last post focussed on the logic of consumption for individuals, but those logics are constantly reinforced by the perceived (deluded) political imperative to perpetually increase the size and speed of the economy. For a thorough and nuanced account of that issue I highly recommend Tim Jackson’s work. The solution is not as simple as ‘degrowth’ which has its own (economic and social) problems. While the fetishisation of growth is deeply problematic, particularly from an ecological standpoint, the fixation on asking ‘growth: yay or nay?’ is not a particularly productive way forward. It’s a fundamental question, but not as fundamental as many seem to think.

What matters more is meeting the needs and aspirations currently met by growth in a sustainable way, and improving the quality of the thing (the economy) that is growing, if indeed it needs to grow. Jackson argues that we can change the operating principles of the macroeconomy — enterprise, work, investment and money — such that enterprise is less about productivity and profit and more about service; work is not a personal sacrifice but desirable cultural participation; investment is not risky speculation that perpetuates debt but a commitment to the future; and the money supply is not a private plaything, but a social good issued by a progressive state.

These issues of economic structure are essential for any serious attempt to go beyond consumerism, but while they are necessary, they are not sufficient. I want to focus here on what I think are the more challenging constraints of the imaginary — the broader ideational struggle to speak not just truth but also beauty and goodness to power.

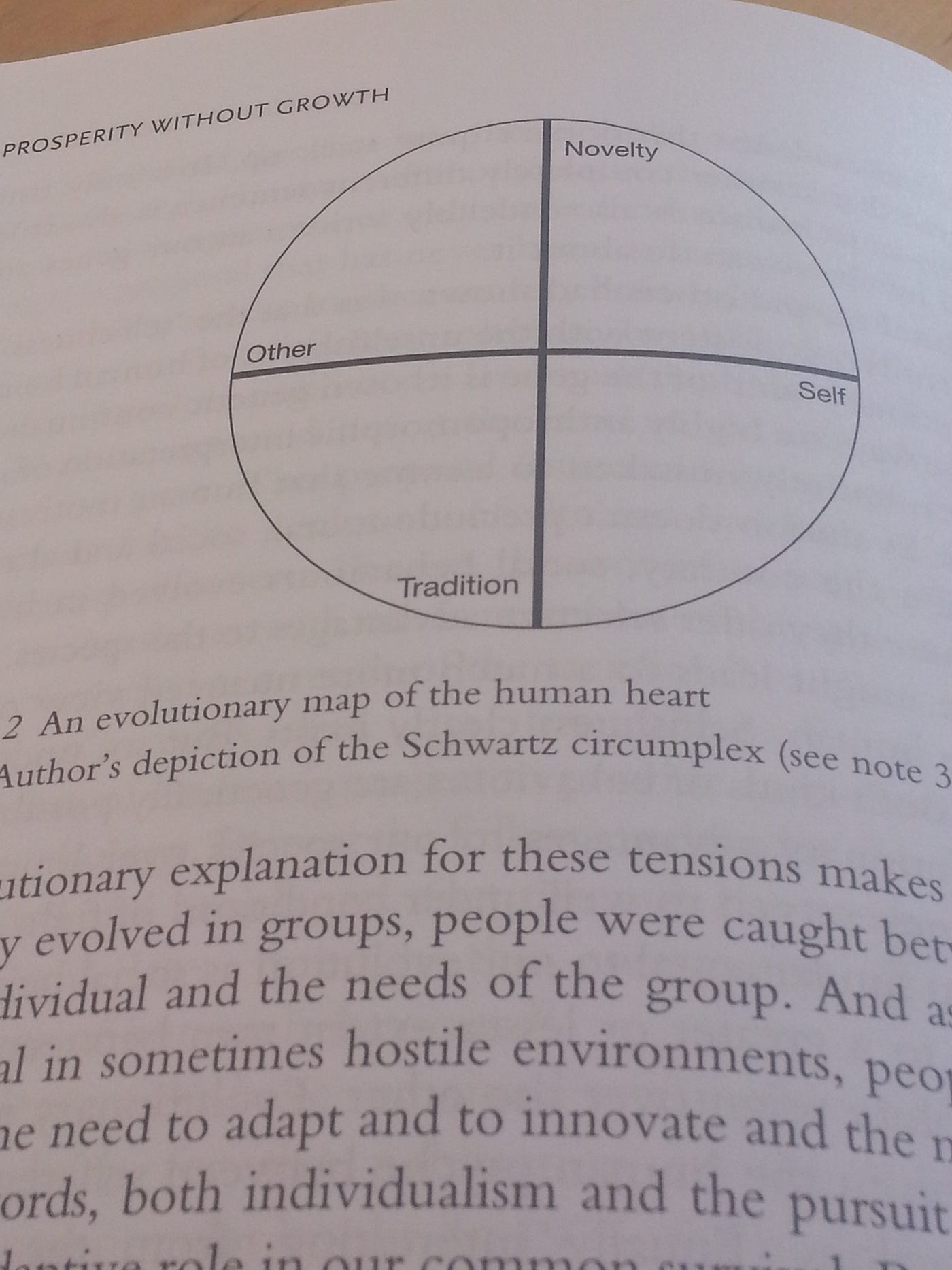

Tim Jackson makes this point particularly vivid in the second edition of Prosperity without Growth (p136) when he reflects on Shalom Schwartz’s values research that leads to an ‘evolutionary map of the human heart’ or ‘circumplex’. With the y-axis marking variations in novelty and tradition and the x-axis marking the extent to which we are self or other directed, Jackson observes that ‘self’ and ‘novelty’ is a legitimate part of the story, but it should be only part of it (roughly a quarter!). Instead, as he puts it: “ What we’ve created in consumer capitalism is an economy which privileges, and systematically encourages, one specific segment of the human soul.”

The resulting feeling that fundamental questions of human and social life are not publicly permissible is reflected in the preeminence and tangible nature of extrinsic and novelty values (eg profit, success, status, fashion) compared to the relatively orphaned and nebulous nature of intrinsic and traditional values (eg friendship, craft, belonging, compassion). This unbalancing is related to the degrading of civic institutions, secularisation, the coarsening of public debate, and the relegation of philosophical questions to private and academic realms.

It was in the context of this maddening sense of intellectual asphyxiation — ‘There is more to life!’ ‘Why don’t we talk about the things that really matter?!’ ‘Why don’t we properly value the things that are really valuable?’ ‘What is this all for?’ — that I won funding to lead a 2 year project on reimagining spirituality at the RSA in London which involved about 300 people directly and many more indirectly (The Political and the Spiritual captures the journey quite well). While considering how to communicate ‘the message’ of the final report, Spiritualise, at the end of 2014, I received a wonderful email from Ian Christie:

I wonder if the framing needs to be about the post-extrinsic? We have had two centuries of a civilisation of unparalleled material progress, abundance and development based on extrinsic values (self-interest, materialism, economic growth, keeping up, social mobility); intrinsic ‘beyond-self’ and religious values have periodically been reasserted but they have lost their institutional hold and centrality to the stories that make sense of our lives. The extrinsic values celebrated by industrial society are now under real pressure in the West as scarcities begin to return and confidence in the future wanes, for good reasons of ecological disruption, social fragmentation and economic dysfunction and inequality.

Well said, and note that ‘post-extrinsic’ doesn’t mean anti-extrinsic — it’s about going beyond rather than rejecting wholesale. A post-extrinsic society wouldn’t necessarily be anti-growth. It would just be very clear that growth is not an end in itself; ends in themselves would become the focus. We would continually debate what they are, but they would coalesce around for instance the good the true, the beautiful; love, virtue and so forth. Particular economic models including ‘growth’ or otherwise would be considered and tested against these kinds of ends, and may or may not be found wanting.

The post-materialist emphasis that appears to be emerging in Nordic countries is a good case in point. Projects like Tech Farm or 29k in Sweden emerge from stable market economies respecting ecological constraints rather than an entirely different economic model. I don’t doubt Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Iceland have major problems to overcome, and they remain vulnerable to world events, but they have reached a stage of political and economic development where questions about how to keep the show on the road have evolved into questioning what the road is made of and where it is leading. Too many people assume that the only alternative to consumerism is something stiflingly communal, technophobic or regressive, but it need not be. Consumerism needs to be tamed and dethroned, but not necessarily eliminated. I am a big fan of book shops for instance.

Harvard Professor Michael Sandel captured the essence of the problem when he said that ‘a society with a market’ has become ‘a market society’. The state and civil society should be proactively socialising and humanising the economy, but instead governments have allowed markets to gradually economise and dehumanise society. In Rowan Williams’s wonderful review of Michael Sandel’s What Money Can’t Buy in Prospect he pinpoints the premise of Sandel’s critique into excessive marketisation as follows:

The fundamental model being assumed here is one in which a set of unconditioned wills negotiate control of a passive storehouse of commodities, each of them capable of being reduced to a dematerialised calculus of exchange value. If anything could be called a “world-denying” philosophy, this is it…a possible world of absolute commodification.

He goes on…Those who know Rowan Williams — a first rate academic philosopher and theologian and incisive social commentator — will know that he chooses his words very carefully, so read the following with that in mind:

If we want to resist this intelligently, we need doctrine, ritual and narrative: sketches of the normative, practices that are not just functions, and stories of lives that communicate a sense of what being at home in the environment looks like — and the costs of failure as well.

I admire Rowan Williams hugely, so I want to try to develop what he offers as the beginning of an answer to the challenge of going beyond consumerism. Each of these suggestions contains a certain amount of ‘logic’ that can meet our ‘human givens’ and counteract the logics of consumption mentioned in the previous post. (The analytical nature of those connections and a fuller development of each idea is beyond the scope of this post.)

Doctrine.

During the RSA project on spirituality the anthropologist Matthew Engelke said of the core term: “the word has a history, and that history has a politics.” The same point applies to ‘doctrine’, but that doesn’t mean we should reject it. Doctrine really just means a shared commitment to certain ideas, principles or values. I would say we have lost that, and we are suffering for the lack of it.

Beyond slightly maddeningly vague and aspirational references to ‘shared values’ we lack shared institutional or textual touchstones to clarify who we are and what we care about — both nationally and internationally. Where we have them -for instance in national constitutions or the declaration of human rights- there is no longer a palpable sense that such things are sacred or even fully accepted.

We need doctrine of some kind to bind people together in a way they would willingly choose to be bound. What we need to foreground is not just laws but the principles and purposes that laws reflect. I would say the front-runners here include human rights but also ‘happiness’, and the hard work begins when you try to develop such notions without violating freedoms. My preference here is for eudaimonia and a detailed account of flourishing. To make that commitment entails that the state has a role in providing conditions conducive to human development and the cultivation of virtues. (There is a subtle philosophical point at the heart of this about human rights being justified through a prior recognition that there is human responsibility to develop).

Ritual.

The world is full of rituals, but most of them have been disenchanted. Football matches, Sunday lunches, walks in the park after school drop off (that’s me), cake for gratuitous celebrations, and even ‘wine o’clock’ which is 6pm at a friend’s house (I often find myself there at that time). Such things add pleasure and texture and meaning to life — I’m not knocking them! — but they are a bit gratuitous and I don’t think they are what Williams has in mind. Rituals may have social elements but they need to point beyond the social to something larger, fuller and deeper. The relationship at the heart of ritual is the relationship between life and death, mediated by elemental forces. The kinds of rituals that fall out of that might be a monthly day of silence, perhaps periodic fasting, perhaps singing around the fire. All such things need to be done as a symbolic testimony to the joy and sorrow of being human, not because they are fun or convenient.

Narrative.

We suffer from a kind of mythic deprivation. We don’t just need ‘new stories’ because we are inundated with stories. The point, as Alex Evans has recently argued, is that we need to bring mythos back into our lives. Evans argues that such myths need to be expansive enough to contain ‘a larger us’ and ‘a longer now’, but how exactly? Isn’t there something absurd about manufacturing myths as tools to solve problems of meaning? Or maybe not, perhaps that’s just what creation and storytelling is about.

I wonder though if the point is that it’s not myths or even meta-narratives that we need. French philosopher Francois Lyotard encapsulated the postmodern attitude as ‘increduility towards meta-narratives’ but he was looking backwards to the meta-narratives of modernity and finding them wanting — lacking the vivid and defining contexts that shape our actions. What we need now is to look forward to the meta-narratives beyond postmodernity. If you want to be precise about it, we are looking for a ‘meta-meta-narrative’. Knock yourself out.

But it’s true. We need ‘a story of stories’ and that story has to be a magnificently inclusive and inspiring vision of how we survive and thrive. And I’m not sure it will be mythic in nature at all, at least not for a few thousand years.

Sketches of the normative.

One example of a ‘sketch of the normative’ is Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics about the social and ecological constraints within which an economy has to operate. It’s an impressive idea and a hugely important contribution, but the economy as such may not be a large enough frame to shift the social imaginary.

The political and philosophical think tank Metamoderna offer a more compelling example of what a ‘sketch of the normative’ looks like. Their forthcoming book The Listening Society attempts to build a comprehensive vision of what society as a whole should be trying to do. Their argument is broadly that one meta-ideology has ‘won’ — basically the Nordic model, and now the challenge is both to steer the world towards that model and then improve it by making the cultivation of the inner lives of human beings the paramount political objective — and that idea is very clearly delineated; it’s not just ‘we should all be better people’ but rather why and how, in what manner for what purpose and to what extent? From those parameter certain policies and economic models become more or less viable and attractive.

I don’t agree with every aspect of Metamoderna’s case by any means and look forward to reviewing their work in detail before long, but it’s refreshing to hear an attempt to ‘sketch the normative’ ie to say ‘this is what I think we should all be trying to do, why, and how we might go about it’ . Alas, this kind of bold and visionary thinking is all too rare.

Practices that are not just functions.

This curious expression is presumably about the importance of undertaking practices that are not co-opted by instrumentality; a defence of doing being in a way that is not subsumed by doing. For instance, meditation is widely practiced and promoted, and rightly so — the research evidence for its benefits to mental health and productivity for instance is very strong. But looking more deeply, the purpose of meditation is arguably purposelessness — it’s about stopping that incessant chain of doing A because of B and B because of C…and Z because of A.

In his commencement address at Stanford, Zen Priest Norman Fischer was adamant that spiritual practice must be “Useless, absolutely useless”:

“You’ve been doing lots of good things for lots of good reasons for a long time now…for your physical health, your psychological health, your emotional health, for your family life, for your future success, for your economic life, for your community, for your world. But a spiritual practice is useless. It doesn’t address any of those concerns. It’s a practice that we do to touch our lives beyond all concerns — to reach beyond our lives to their source.”

More generally the idea of practise is important. German Philosopher Peter Sloterdijk is both a respected scholar and a former follower of Indian Mystic Osho. In his 2013 book You must change your life (p11) he states: “In truth, the crossing from nature to culture and vice versa has always stood wide open. It leads across an easily accessible bridge: the practising life.”

The challenging aspect of this emphasis on practise is that it ceases to work once you formalise it. Once you say ‘let’s set aside an hour a day to do our own thing for its own sake’ you’ve already undermined the idea. There is something of the ‘relax!’ and ‘be spontaneous!’ paradoxes here — you can’t capture and operationalise something where the value inheres in being non-instrumental.

Stories of lives

We envy too much and admire too little, partly because the latter emotion takes longer to cook. Most of us are surrounded by like-minded people living broadly similar lives, but there are so many ways to live well, and we don’t hear enough examples to expand our imagination of what is possible. Our thoughts are so bound up in projection — we see ourselves in others, but rarely manage to see the otherness in others because we are not actively encouraged to. The example that comes to mind is a BBC documentary about an Australian man who rescues baby kangaroos from the highway and nurses them back to health on his small farm — watching that documentary expanded my notion of what it might mean to live well, and not because I have a sudden interest in tending to baby kangaroos.

A sense of what being at home in the environment looks like.

Matthew Crawford’s work about the importance of working with your hands and the need to protect ‘the attentional commons’ (‘the right not to be addressed’) is very helpful in making sense of what ‘being at home in the environment’ looks like. As Crawford puts it: “We find ourselves situated in a world that is not of our making.” For Crawford, ‘getting real’ means at least three things: working with material reality, acknowledging other people and the inheritance of the past. We need to embed such things in our daily engagement in the world to resist the flights and fancy and projection that arise through over-emphasis on textual understanding and the virtual world.

And the costs of failure as well.

None of this sounds easy, but we don’t really have a choice. In an essay published in 2014 — Spirituality and Intellectual Honesty — philosophy professor Thomas Metzinger wrote the following challenging words:

Conceived of as an intellectual challenge for humankind, the increasing threat arising from self-induced global warming clearly seems to exceed the present cognitive and emotional abilities of our species. This is the first truly global crisis, experienced by all human beings at the same time and in a single media space, and as we watch it unfold, it will also gradually change our image of ourselves, the conception humankind has of itself as a whole. I predict that during the next decades, we will increasingly experience ourselves as failing beings.

Will we increasingly experience ourselves as failing beings? Perhaps we do already? But while I hate facile positive thinking as much as the next person, I’m not ready to give up. Developing Rowan William’s suggestions above is a good start, but the deeper and related hope, surely, lies is in Metzinger’s premise — “the present cognitive and emotional abilities of our species”. Those abilities of our species are not fixed.

We know, as well as we know anything, that human beings can grow and change for the better. And it’s no longer optional. In fact it’s the new categorical imperative. We simply have to understand what it means for human beings to grow and develop and think about what follows for political and civic institutions and social and economic policy. It’s no small task, but you have to start somewhere, so that’s the subject of my next post.

The Cognitive and Emotional Abilities of Our Species (March 21, 2017)

In part one we examined the extraordinary tenacity of consumerism despite the evidence against it, and in part two we alighted on the idea that in order to go ‘beyond consumerism’ it might be necessary to improve what German Philosopher Metzinger calls “the present cognitive and emotional abilities of our species”.

What does that mean, and how do we do it? The first question is our focus here, and the second is for the final post in this series.

But before plunging in, let’s keep the promise in mind —we are looking for a much more penetrating understanding and engagement with the major challenges of our time, not least climate change — this applies both in terms of greater capacity of those working on the problem, and richer diagnosis of the human dimensions of the problem.

We also need to begin by understanding that this idea of pro-active human development feels uncomfortable or subversive to many, and simply obtuse to others. For starters it sounds like a truism: if people were better, the world would be better! And yet the thing about truisms is that they tend to be…true. What is more interesting is when something is clearly true but politically neglected because it doesn’t seem like normal practice.

Again, we need to think at the level of the imaginary to make sense of perplexing attitudes and actions, in this case why we don’t think developing human beings in a systematic way is a legitimate political issue beyond childhood.

As Charles Taylor puts it in Modern Social Imaginaries(Public Culture 14(1): 91–124, 2002): The social imaginary is “a wider grasp of our whole predicament”. Also, it is “not a set of ideas; rather it is what enables through making sense of, the practices of society.” Taylor goes on to write about ‘the moral order’ or ‘moral background’ of a society which has changed through secularisation:

“Humans have lived for most of their history in modes of complementarity, mixed with a greater and lesser degree of hierarchy. There have been islands of equality, like that of the citizens of the polis, but they are set in a sea of hierarchy once you replace them with the bigger picture…What is rather surprising is that it was possible to achieve modern individualism — not just on the level of theory, but also transforming and penetrating the social imaginary…”

Taylor traces the source of default individualism in the west to reformed Christianity, particularly the rejection of ‘higher vocations’ (eg the monastic life) and the notion that if everybody is 100% Christian regardless of vocation the normal lives of the vast majority are as hallowed as any other. He adds, tellingly: “Indeed, it is more sanctified than monastic celibacy, which is based on the vain and prideful claim to have found a higher way.”

Taylor argues that this is the basis for subsequent democratisation and the sanctification of ordinary life, and also the anti-elitist thrust of modern civilisation:

“The mighty are cast down from their seats, and the humble and meek are exalted. Both these facets have been formative of modern civilization. The first is indicated by the central place given to the economic in our lives and the tremendous importance we put on family life or “relationships”. The second underlies the fundamental importance of equality in our social and political lives.”

Taylor also pinpoints how ‘society’ became ‘economy’ which began its life being contrasted with “the wild destructiveness of the aristocratic search for military glory”.

“Instead of being merely the management, by those in authority, of the resources we collectively need, in household or state, the economic now defines a way in which we are all linked together, a sphere of coexistence that could in principle suffice to itself, if only disorder and conflict didn’t threaten. Conceiving of the economy as a system is an achievement of eighteenth century theorists but coming to see the most important purpose and agenda of society as economic collaboration and exchange is a drift in our social imaginary, which begins in that period and continues to this day. From that point on, organised society is no longer equivalent to the polity; other dimensions of social existence are seen as having their own forms and integrity. The very shift in this period of the meaning of the term civil society reflects this.”

Taylor’s thinking about imaginaries is vital context to show why the development of our inner worlds as a political project feels obtuse for those who are used to thinking in terms of systems and structures of society like economy and democracy, rather than the unfolding of the psyche over time, which has religious undertones.

For the academically minded the idea of ‘making people better’ sounds like a questionable value judgment but also a little too close to ‘personal development’ and ‘coaching’. Neither are harmful in themselves, but they evoke wariness because products and services can be sold through theories of ‘better selves’ mis-sold as science. For sociologists and critical theorists the idea evokes incredulity because it sounds like it’s about the individual detached from social structure, while also being paternalistic and therefore a prospective abuse of power. And for politicians it is a slightly toxic and elitist idea because emphasising different levels of human development means the relatively ‘well developed’ have to be considered in some questionable sense superior to others.

I share these reservations now because there is a certain cliquishness among theorists of human development, many of whom are trained as philosophers, psychologists or psychotherapists or work in leadership or management studies. I have noticed that when I introduce some of the ideas below to socially, economically and politically minded audiences it is really hard work to make sense of what I am saying at all, never mind why it should matter to them.

This lack of receptivity to human development is a huge challenge. And it’s not just a conceptual challenge, but part of the constraints of our current imaginary. It’s also a central part of the challenge of seeing beyond consumerism because it offers a viable way out — if only we could see it! Properly understood, human growth is much more sustainable than economic growth, and far more deeply rewarding. It is part of the normative vision of the good life that we need to redirect our systems and structures.

The quick answer is to say to such people: ‘please invest some time trying to understand human development, and then we’ll talk’. But why should they? There are so many things to read and think. I have no simple or immediate answers here, but we need to make the ideas more vivid and compelling. This lack of cultural and political receptivity to human development is a real and live issue for my organisation, Perspectiva, and we will soon be starting a project on making human development clearer, more accessible and more relevant.

What, then, does it mean for human beings to grow?

The first challenge is that ‘grow’ alludes to, inter-alia, improve, transform, deepen, learn, unlearn, evolve, develop, expand, attach, detach, mature, cultivate, integrate. Physical growth is easy enough to measure, but as this plethora of growth-related terms suggest, it’s not so clear what exactly the relevant variable and/or active ingredient is when it comes to human beings getting ‘better’. Worse still, many theories lack a broader vision of the good life against which to test their model with analytical rigour.

Variables include the type of development; emotional, cognitive, volitional, moral, virtue, and possibly even spiritual development. And in each case there are competing theories, with different kinds of ontological and epistemological assumptions, and only partially commensurate evidence bases. Then there is the unit of analysis question; is it the ego, the person, the self, the mind, the soul? Finally there is the scope. Some theories are domain specific, applying for instance to leadership or teaching or relationships, and some are domain general. Borrowing from Marx and Engels, you might say the problem with human development praxis is that it doesn’t have class consciousness. It is a field ‘in itself’ but not yet ‘for itself’.

My own favourite theory is Robert Kegan’s, which is outlined as follows in an excellent Summary document by JG Berger:

“Robert Kegan’s theory of adult development (1982 — The Evolving Self; 1994 — In Over our Heads) examines and describes the way humans grow and change over the course of their lives. This is a constructive-developmental theory because it is concerned both with the construction of an individual’s understanding of reality and with the development of that construction to more complex levels over time. Kegan proposes five distinct stages — or “orders of mind” — through which people may develop. His theory is based on his ideas of “transformation” to qualitatively different stages of meaning making. Kegan explains that transformation is different than learning new information or skills. New information may add to the things a person knows, but transformation changes the way he or she knows those things. Transformation, according to Kegan, is about changing the very form of the meaning-making system — making it more complex, more able to deal with multiple demands and uncertainty. Transformation occurs when someone is newly able to step back and reflect on something and make decisions about it. For Kegan (1994), transformative learning happens when someone changes, “not just the way he behaves, not just the way he feels, but the way he knows — not just what he knows but the way he knows” (p. 17).

I admire Kegan’s model because it is distinctive and capacious enough to relate to the myriad of variables that make the field so messy; in this sense it is a theory that walks its own talk. I got to know Kegan’s theory well when I took his celebrated Adult Development class as a masters student at Harvard in 2003. I kept up with his work and was honoured to chair an RSA event with him just over a decade later.

So I am clearly biased, but here is the pitch anyway: Kegan’s theory is philosophically and psycho-dynamically rich. It is informed by related theories (Erikson, Rogers, Kohlberg, Loevinger, Gilligan, Torbert) and by Kegan’s training in humanities and as a therapist, and it is vividly illustrated through literature and popular culture. However, at heart it is fundamentally a deepening, refining and extending of Piaget’s groundbreaking work in genetic epistemology. That theory has naturalistic roots in open systems biology and ultimately amounts to a theory of the nature and evolution of consciousness. Kegan’s theory also has a clear active ingredient, which is meaning-making — the domain-general ‘thing’ that evolves. It has a profound explanatory mechanism for development in the form of ‘the subject-object relationship’. It offers a considered account of social and cultural influences on the psyche (hidden curriculums). It has an established empirical methodology (the subject-object interview) and some clear practical applications (eg immunity to change exercises). It is no accident that the American integral philosopher Ken Wilber who has expertise in psychological modelling says, approvingly: “With Kegan, you become a ditto-head” (The Eye of Spirit 2001, p216). Further details for my appreciation for this model are detailed in the Perspectiva post: The Unrecognised genius of Jean Piaget.

However, while Kegan’s model coheres beautifully at a theoretical level it does have some limitations. His preferred methodological approach — The Subject-Object Interview — is well suited to the complexity of meaning-making — it involves probing for structure in people’s interpretations of lived experience, figuring out what they are ‘subject to’ and what they can ‘take as object’. It takes about 90 minutes and leads to a transcript that has to be carefully coded and then checked for inter-rater reliability with trained coders. So not only is it an interview and therefore a particular kind of contrived situation and performative context, but it is also impractical to scale and expensive to administer. Perhaps for this reason, there is limited empirical evidence for the model’s validity, which amounts to two smallish samples (342 in 1994; 497 in 1987) of a particular cohort (middle-class college-educated professionals). Those studies give some idea of how the population breaks down in terms of their meaning-making capacity, but we can’t really infer anything from it in political or policy terms. I believe we need a well-designed meta-study that connected the interview to a simpler device from a less comprehensive but commensurate theory (for instance the Washington Sentence Completion Task) with a high degree of confidence, and then you can speak with greater confidence about whole populations. Anybody willing to fund such an endeavour would be doing the world a huge favour!

Kegan also conflates age and experience in a way that I, as one of his biggest fans, find embarrassing. For instance he suggests that only those in late middle age and above even have the possibility of reaching his highest levels of development, which feels approximately right, but analytically wrong. Aldoux Huxley writes that experience is ‘not what happens to you, but what you do with what happens to you’ which sounds like the kind of experience that matters in this context, and is only loosely related to age. A related limitation of Kegan’s model is the lack of emphasis on how human development is experienced phenomenologically and what might motivate us to pro-actively complexify our consciousness.

Renowned social psychologist Mihaly (‘flow’) Csikszentmihalyi co-authored an extended book chapter with Kevin Rathunde in 2014 called The Development of the Person: An Experiential Perspective on the Ontogenesis of Psychological Complexity. This essay begins by reflecting on what it means to be a person, and argues that psychological complexity is ‘the central dimension’ to personhood, and that this complexity evolves over the life cycle. The argument is structured by asking what it means to live well and age well and what kind of person we would like to be in our latter years. It then works backwards towards the kinds of opportunities, challenges and experiences we might need to become that kind of person. What this paper adds to Kegan is a particular kind of intrinsic value that lies at the heart of human development, namely the experience of ‘flow’ — deeply rewarding absorption in a task where our skill level and challenge level are well matched.

The claim is quite striking in its simplicity. We are propelled towards the complexification of consciousness by the pursuit of flow experiences. If we have too much skill for the challenge we get bored; too little we get anxious. The ideal world, on this account, is one where we are spend a significant amount of time on the cutting edge of our own competence — that’s where we’ll find flow, intrinsic meaning and complexification of consciousness. The social and political challenge becomes how to create such a world.

The Listening Society, the first book by Hanzi Freinacht of the Nordic political and philosophical thinktank, Metamoderna rises to almost exactly that challenge. The book will become available within a few months and deserves a thorough review elsewhere. I mention it here because while Hanzi doesn’t emphasise flow as such, he does an excellent job of critiquing the tendency of existing models to mash together lots of distinct phenomena. He also develops Csikzsentmihaly and Rathunde’s critique of Kegan by emphasising the cultivation of positive subjective states as well as dispositional traits.

Metamoderna positions human development as the central theme in their political philosophy and in their positioning as leaders of ‘The Alt-Left’. Their political premise is that one ‘meta ideology’ has won the battle for how to structure societies for the time being, and they call this ‘Green Social Liberalism’ — basically the generic Nordic model where “the games of everyday life become milder, more sensitive, fair and forgiving.” They point to the pragmatic case for the resolute acceptance of the market economy and equally resolute acceptance of the welfare state, gradual adaptation to globalisation, roughly 50/50 breakdown of public and private sector, basic liberal values and ecological awareness.

Metamoderna then point out that even though this is currently the best we can do in terms of balancing political interests, it is still very far from ideal, and inadequate to the ecological, social and existential crises we face. They then propose ‘‘Green Social Liberalism 2.0’ which is ‘an extremely social, extremely libertarian and extremely green society’ — that means a welfare system that is expressly designed to meet the psychological, social and emotional aspects of human beings. Their model of human development is therefore constitutional in a manner of speaking and takes over 200 pages to delineate because it’s their premise for an enlightened social policy.

Hanzi helpfully distinguishes between four main features of human development, alighting on the confluence of cognitive stage (based on the theory of hierarchical complexity of Michael Commons), cultural code (eg modern, postmodern), subjective state (how happy/sad) and depth (range of experience of subjective states) and then suggests we could ‘score’ people on their ‘effective value meme’ which combines each of these.

This demarcation of stage, code, state and depth is very useful but it also begs a lot of questions. Although these four cover most of what matters, they feel a bit random, and don’t emerge from a background theory of human cognition or evolution or morality. I also have qualms about commensurability. Clearly each of these phenomena has a different ontology. That’s only a problem because it’s hard to imagine a methodology that would give a credible ‘score’ that would be empirically valid and socially acceptable. And that’s a problem because it would mean the psychological premise for social policy has not yet been established in sufficient detail.

I will say more about Metamoderna in due course, but it is encouraging and inspiring to see a systematic attempt to connect a detailed account of human flourishing with the outline of a policy platform. This is precisely kind of connection between the inner world and the outer world that I want Perspectiva to speak to, but we will have different philosophical premises and political conclusions. In the final post, I will try to outline what these theories of human development mean for the diagnosis of our current predicament, and the social and economic infrastructure of a post-consumerist society.

What do we do? (March 22, 2017)

In part one we considered the logic of consumerism in the context of human needs and our current imaginary. In part two we considered what it might take to reshape the imaginary through alternate social and emotional logics with greater intrinsic value. And in part three we considered the intrinsic (and extrinsic) value of human development, why this idea is so important politically and why it has been resisted for so long. There is so much more to say at each stage, and many more stages, but for now I want to end this mini-series with the question everybody always wants to ask:

What do we do?

Let me confess that I don’t really have an answer, but I do have some sense of what an answer might look like. The point of the emphasis on human development is this: we urgently need to understand what we are all ‘subject to’ at a perceptual and epistemological level and how that constrains our sense of what is politically necessary and possible. At a political level we are subject to economic growth and at a societal level we are subject to consumerism — they have us, we don’t have them. That’s what has to change.

Clearly there is no panacea. It is tempting to think we could change one thing and everything else would readjust seamlessly and beautifully, like some kind of societal acupuncture. ‘If only everybody became vegan’ or ‘if only everybody stopped watching TV’ or ‘if only everybody meditated for half an hour every day’ or ‘if only there was no commercial advertising’…if only such things happened the people of the world would have a chance to know themselves again and everything would improve.

There is some truth here — some changes are more transformative than others, and a world without advertising where people meditated every day would probably be a good start — at least for me- not least because it would support human development, but how can you really say? And what would my commercially minded uncles say? Such ‘if only’ ideas don’t inspire hope unless they are part of a larger vision that is politically astute, that meets people where they are and is not selectively coercive in spirit.

The same point applies to policy ideas relating to carbon taxes, citizen incomes and shorter working weeks — we should campaign for what we believe in — of course — but most changes in public policy are likely to be coopted by the prevailing imaginary. Take ‘green growth’ or ‘inclusive growth’. Typically these are expressions devised by people who could care less about growth but care deeply about ecological sanity, human dignity and solidarity. Alas they don’t — because they feel they can’t — fight for such things on their own terms. The result is to reinforce the imaginary that corrodes the sources of value we think we are protecting.

The world is also moving too quickly and too unpredictably for static visions that sound utopian. The idea of saying the world should be like Z, the barriers to getting there are X and therefore we should do Y also doesn’t ring true, if only because the rest of the alphabet rushes in from stage left and spoils the whole show. There is just too much going on, and so much energy is spent on simply coping with events. Partly because of the direct and indirect effects of climate change, that’s more likely to get worse than better in the coming years. It’s like we are in the middle of the ocean and hopping between boats. What we really need is land, but we can’t get there because we can’t see it.

That land is a new imaginary, which effectively means rewriting the cultural code. We don’t get there by going on a march saying: “What do we want? A new imaginary! When do we want one? Now!” The imaginary is constituted by institutions and policies and practices so changing it means changing them too. But here’s the crucial point. We have to keep the target in mind. We are not trying to change human nature, but rather shift the normative foundations of society such that neglected aspects of our natures are better acknowledged and attended to.

This is why Perspectiva seeks ‘a more conscious society’ — we need to wake up to how the world is shaping us before we can properly shape the world. And part of that waking up is a renewed sense of purpose and direction at a fractal level — from individuals to families to communities of interest and practise, to countries, to the world as a whole. We should not be content just to keep the show on the road, but let’s rather improve the show, improve the road, and if the road seems to be going nowhere in particular, let us make a ‘show’ that reflects on that experience to help us transcend it.

To contextualise what it might mean to wake up in practice, The New Citizenship Project seems to have one main message and it’s a good one — namely that we should resist the idea that we are just consumers, and fight for recognition as citizens instead — hence #Citizenshift. This is important, not least because it looks like Barack and Michele Obama will be emphasising the importance of citizenship for the foreseeable future. It is part of ‘sketches of the normative’ that Rowan Williams alluded to in the second post.

Why should citizenship matter? Because it’s an intentional stance towards life. It’s a form of maturity and part of being awake to the world. It’s a way of meeting others as moral equals in a form of benign activity and inquiry. It also about believing that the true, the good and the beautiful should be given a chance, and that they will prevail if they have the right kind of hearing. The challenge, then, is to make places and times for citizenship to manifest.

A useful contrast might be The Sunday Assembly whose motto ‘Live better, help often, wonder more’ is galvanising on its own terms, but such generic injunctions will inevitably be coopted by the imaginary. Unless you explicitly connect ‘living better’ to an idea of the good, ‘help often’ to an experience of compassion and ‘wonder more’ to a form of contemplative practice you may entertain and enliven but you will not meaningfully change the world. Perhaps we genuinely need vivifying communal entertainment to break free of consumerist habit energy, but if so, let’s not be shy about saying that.

The New Economics Foundation has been trying to present an alternative vision of the world for years, but why does it never seem to quite cut through? I think because it doesn’t deal with the inner world at all, and lacks appreciative inquiry about world views (eg libertarian or conservative) that are different from their own. That might change now under the leadership of Mark Stears, which seems to have started well. However, their new ‘take back real control’ emphasis is second hand injunctive language; it adopts the prevailing narrative of anxious grievance but sidesteps the materialist imaginary that has created it. The Club of Rome also appears to be trapped in a way of communicating that is about presenting a problem with evidence and suggesting a solution with evidence. The problem is that as long as the normative basis or ‘moral order’ of society is only discussed at the level of the things outside (the economy, ecological limits) and not the things inside (love, compassion, human growth) the immune system of the status quo will adapt and absorb external changes in a way that leaves the imaginary untouched.

I make these judgments with limited information, so I could be wrong, and apologise for any unfair generalisations. But I am keen to emphasise that you need to commit to something gently subversive. And for that, you need to know what you are against as well as what you are for, without perpetuating the divisions that keep us exactly where we are. That’s why I co founded Perspectiva. The ‘story of stories’ we need is one where competing visions of the world and incommensurate values can be fully expressed and co-exist in harmony, without the harmful pretence that there are no objective values or criteria to judge one form of life better than another. To get there we need to dig deeper into ontological and epistemological foundations of the imaginary. That means looking more quizzically at the nature of life as such, how it gives rise to consciousness, how moral intuitions form, how people, institutions and societies change. From that depth, we hope, a clearer sense of aesthetic unity and purposive pluralism should arise.

But I still haven’t answered the question! What should we do? To force my hand, I’m going end with some numbers. Stand back.

Primum non Nocere. The first thing doctors learn in medical training. First do no harm. We need to protect human rights, uphold a free press and the rule of law. Fight wholeheartedly for the value of the truth. Know and value what democracy means. Shine light inside black boxes full of data used to perpetuate consumerism. And fight for a viable and desirable planetary habitat…don’t let civilisation fall apart.

Speak truth, beauty and goodness to power. In all of these battles, don’t be merely defensive or utilitarian. The pillars of our civilisation have normative, emotional and spiritual elements that need to be brought to the surface. As Rowan Williams puts it: Moral imagination won’t kill you, but the denial of it will, both literally and spiritually. Let’s have the courage to say what we really think and feel, not merely what seems to be culturally permissable. We need to speak up for the ecological and civic foundations of our world, yes, but in a way that recognises why they are under threat. There is far too little of the human in human rights; far too little virtue in virtue signalling.

Keep it complex, but make it clear. This statement is (or at least should be) a rallying cry for The Alternative UK. We can’t really know the world if we’re afraid to use the world epistemology. We can’t get real if we are too shy to analyse problems at an ontological level. We can’t defend the soul if our only legal tender is the language of matter. We can’t reimagine the economy if growth is always an answer and never a question. Yes, we need to meet people and politicians where they are, but we don’t have to stay there. It’s ok to enrich the conversation with ideas and language that expand horizons.

Campaign for ‘larger lives’. Roberto Unger captures the underlying purpose when he writes: “A progressive is someone who wants to see society reorganised, part by part and step by step, so that ordinary men and women have a better chance to live to a larger life.” A larger life is good lodestar for progress. It refers to “a life of greater scope, greater capability and greater intensity” and that’s not so difficult to comprehend. We can all do and be more, with growing aptitude and wisdom, and experience life more fully and deeply as a result. Of course that means we all need to have a place to live, work to do, and the education and time we need to do it, but crucially those things are the socio-economic means to the experiential ends that ultimately matter. I therefore think it’s time for ‘progressives’ to speak about experience as such, in the explicit and evocative terms we need to cut through ambient distraction — the language, for instance, of the deepest currents of life; love, death, self and soul. When Russell Brand said the problem is primarily spiritual and secondarily political it was a minor tragedy for progressive thought that this timeless message was subsumed by its messenger.

Keep on asking — who am I? But don’t expect an answer. As the question becomes more salient and pressing, you will probably find that buying things doesn’t work and will hopefully feel compelled to look for answers in what you care about most in the world. Enduring self-knowledge arises through encounter. For me that came principally from waking up to climate change. I believe most of us know what we need to encounter to become who we are, and that encounter often takes a civic or political form.

Speak freely about the ‘complexification of consciousness’ and ongoing human development. We considered this in more detail in part three but we will need to keep talking about it until people get tired of hearing it and start trying make sense of it and acting upon it.

Think systemically, but don’t forget systems are not machines. Everything is connected, literally, but the active ingredients that are most powerful are people’s hearts and minds. Nora Bateson is a pioneer here. We need to get better at thinking in terms of systems yes, but we also need to realise that the way we see them is part of their nature. There might, for instance, be a story of renewal that combines ‘democratising the means of production’ through new organisational forms; blockchain technologies and 3D printing, and that might hook up with new forms of Government finance, say ‘universal basic income’ derived from carbon taxes at the source of fossil fuel extraction, and it looks like you might have a new system. But if the souls are the same, if the social logics are the same, and the imaginary is the same, we won’t achieve the ends — eg survival, meaning, purpose, love — that we seek.

Connect policy design to the redesign of the imaginary. The value of universal citizens investment (universal basic income with a name that helps) is partly about shifting the societal emphasis from ‘jobs’ to what Tim Jackson calls service or perhaps just ‘meaningful activity’. The value of putting a price on carbon is to raise consciousness of the hidden ecological resources that make the economy possible. The point of proportional representation is to make more citizens feel more invested in the political process. And so it goes on. There is the work you do with the policy and the work you do on what the policy means for shifting the imaginary. We need both, with a renewed emphasis on the latter.

Be hopeful, not optimistic. It has become conventional to distinguish hope from optimism but it’s important. The hope we need is the sense of meaning that comes from facing reality. It’s about fighting the good fight to know reality better, learn from it and then push it towards a better version of itself. But such hope needs a home too. To get beyond consumerism, to create a new world, we have to protect and create institutions that allow us to refine our epistemic perceptions and expand our moral imaginations. It will take time, and many legions, but I hope Perspectiva might be one of many leading the way.

There is no tenth point, alas, because this is not a ten-point plan…

Deeper into Wellbeing (March 23, 2017)

If there was a spokesperson asked to convey the general public’s wavering attitude to personal growth I imagine they would sound something like this:

“So lifelong learning is fine. Maturing is good. Being conscious is necessary. The unconscious is a thing, yes. Doing therapy is normal but not exactly encouraged. Meditating is cool but only really as an antidote to stress. Wisdom is good. We all need to grow up. Becoming more virtuous is a bonus, but sounds a bit pretentious. Childhood development is normal. Adult development sounds plausible but we’d need to talk about it. Emotional intelligence is definitely ok. I’ve heard the brain is plastic, so yes, some changes might be possible in later years. Transformation is encouraged, yes, though to be honest we don’t really know what it means. Self knowledge and self awareness are an important part of our ethos. It’s good to work on your ego, yes, because it can cause a lot of trouble. Better relationships — we’re all for that. We’re easily manipulated to buy stuff so it’s good to be aware of how that happens. Self esteem is very important. Personal development is generally a good thing, but we like to know what’s going on. Social skills? Of course. You grow into new things, and you grow out of other things. Ethical training is sometimes necessary, but it’s human judgment that really matters. Common sense, you know. And goodness, sometimes just basic goodness. Some people have more life experience than others, I suppose. Mindfulness can really help with, you know, the mind. I’ve noticed empathy is fashionable, but I wonder what it really feels like. Willpower matters a lot, but it’s hard. It’s always good to question your assumptions if you can, so anything that helps with that is welcome. Wellbeing? Absolutely! Happiness is even better. Flourishing, yes, we’ll have some of that too. Spirituality might be ok, but I’ll need to check. More generally we just need to get things in perspective.”

There is something weird going on. This imagined statement is just a way to reflect that people generally ‘get’ the idea of human growth and the value of it, but it remains somehow nebulous and peripheral. Perhaps that’s because it seems to be too many things. People notice the particular features of what it might mean to grow as a human being, but there is no collective consciousness of an overall pattern, or why it might matter in any social or political sense.

The point of Perspectiva’s emphasis on human development is this: we urgently need to understand what we are all ‘subject to’ at a perceptual and epistemological level and how that constrains our sense of what is politically necessary and possible. At a political level we are subject to economic growth and at a societal level we are subject to consumerism — they have us, we don’t have them. That’s what has to change. And there are many layers to this idea, for instance to grasp climate change in all its multi-faceted complexity you need a complex mind, and if you don’t grasp it, it’s hard to know what to do about it or even feel why it matters. So a focus on human growth — in addition to its intrinsic value — is a bulwark against the fetishisation of economic growth as a solution to all problems. and therefore timely and perhaps even essential.

Nobody really flinches when you say wellbeing should be the overall aim of the economy, and many organisations and countries have been working towards that goal. For instance the UK Office of National Statistics asks these four questions every year:

overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?

overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?

overall, how happy did you feel yesterday?

overall, how anxious did you feel yesterday?

A great deal of thought went in to those questions and I even played a small part in the process at the time (from 08.15). But they are all about how people feel. This matters greatly, and according to some reflections from Gallup it may even have helped the UK predict Brexit if we’d been paying attention. But still, it’s not the whole story, or even the best part of it.

‘Human growth’ doesn’t compute in the same way as wellbeing, but it is a significant element of wellbeing, and — here’s the neglected point — the element of wellbeing most closely connected to the kinds of capabilities called for to address our social and political challenges. (Bildung is perhaps the concept most precisely relevant here, because it connects human growth to political context, but that discussion is for another time.)

People have an intuitive feeling for ‘hedonic wellbeing’ which is basically about pleasurable experiences, mostly measured through self-reports. Granted, more sophisticated thinkers like Paul Dolan go beyond this simplicity — he defines happiness as ‘the experience of pleasure and purpose over time’. But it’s not just about purpose. Eudaimonic wellbeing is a much more complex notion tied to a vision of the good life. Perhaps the ostentatiously Greek name puts some off, but for those who know it, it’s an inspiring notion. It literally means good (eu) spirit (daimonia) and it has many implicitly spiritual aspects. One of the main models by the psychologist C. D. Ryff includes the following six elements. Note that the first two link very directly to ‘human growth’ while the others are indirectly related.

Autonomy

Personal growth

Self-acceptance

Purpose in life

Environmental mastery

Positive relations with others.

At a political level hedonic wellbeing is favoured over eudaimonic wellbeing for ideological and pragmatic reasons. Providing the conditions for pleasurable experiences is a relatively ‘hands off’ approach and also probably much easier (and cheaper) to measure. In short, it is a form of wellbeing that fits the prevailing imaginary and doesn’t get in the way of perpetuating consumer society. But what if ‘going beyond consumerism’ means not just changing our idea of wellbeing but proactively supporting eudaimonia through social and economic policy? Some have already touched on this idea by suggesting that the universal citizens investment (commonly and unhelpfully known as ‘universal basic income’) is about dealing with the lower levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs so that we can freely pursue the higher levels. One of things that stops the prevailing majority buying in to this, I think, is that the implicit idea in eudaimonia, human growth, is too diffuse to be prioritised and too complex to measure with conviction. As indicated in a previous post, there are many aspects to this challenge:

The models of development are not often theoretically grounded in a broader theory about the nature of life, evolution or change so they are ignored or rejected without any sense of intellectual dissonance.

Many theories lack a broader vision of the good life against which to test their model with analytical rigour — we can’t say what ‘better’ is (eg more courageous) unless you have a prior vision of the good in more general terms (eg courage as the preeminent virtue, making possible all others).

There is little consistency in the relevant variable and/or active ingredient is when it comes to human beings getting ‘better’.

The type of development in question varies: emotional, cognitive, volitional, moral, virtue, spiritual.

The competing theories have different ontological and epistemological assumptions, and therefore only partially commensurate evidence bases.

The unit of analysis varies; sometimes it’s the ego, the person, the self, the mind, the soul.

Some theories are domain specific, applying for instance to leadership or teaching or relationships, and some are domain general.

Borrowing from Marx and Engels, you might say the problem with human development praxis is that it doesn’t have class consciousness. It is a field ‘in itself’ but not yet ‘for itself’. And this matters because there is more to human development that wellbeing.

From a more sociological angle, cultural theorist Theodor Adorno speaks of “the ontology of false conditions.” That sense of false consciousness, of not being able to access the world as it is partly because powerful interests don’t want us to is implicit in The Sociologist Bauman’s famous statement of our present condition: “Never have we been so free, never have we felt so powerless.” To hammer this point home, Political Scientist Stephen Eric Bronner puts the same point as follows (A Very Short Introduction to Critical Theory p77):

“At stake is the substance of subjectivity and autonomy: the will and ability of the individual to resist external forces intent upon determining the meaning and experience of life.”

Relatedly, I argued in Beyond the Big Society that there is a strong social and political case for working on the complexification of consciousness, and that case is only loosely related to wellbeing. This idea builds upon work by the OECD about core competencies we need to survive and thrive in the 21st century, all of which make hidden demands on mental complexity. As German Philosopher Metzinger has said, we risk becoming ‘failing beings’ because many of our challenges are beyond ‘the current emotional and cognitive capacities of our species’. Rather than just give in to that, why not focus on that aspect of the challenge more directly?

With this in mind, I would like Perspectiva to host, lead, curate, convene, design, create and just do an inquiry into the slippery question ‘what does it mean to grow?’. This project will have:

A research leadership side: Building coherence among models, making distinctions, sharing the evidence base and working towards a model that captures key elements of eudaimonia but also speaks to the growth of mental complexity more generally.

A policy application side: The emphasis will be on policy and politics rather than organisations or business or personal development(because so many already do that). What do we know about ‘the hidden curriculum’ of going beyond consumerism, surviving social media, addressing climate change, or safeguarding public health? What are the implicit challenges on *how* we know in such cases?

A socially reflexive side: This is the critical point that is often overlooked, and which I want to focus on here. How do we inculcate a developmental ethic across society, ie a society where human growth is viewed as a shared endeavour with value for the common good?

On the last of the three points — the reflexive side is the most subtle but also perhaps most important. It is easy to spend a lot of time and resources trying to figure out which adult development model is ‘right’ and all too possible to create a very persuasive evidence base that is ignored by policymakers. Both conventional approaches miss the point about the prior importance of cultural receptivity. We are reflexive creatures and that we will grow partly by reflecting on the idea of growth and how we relate to it.